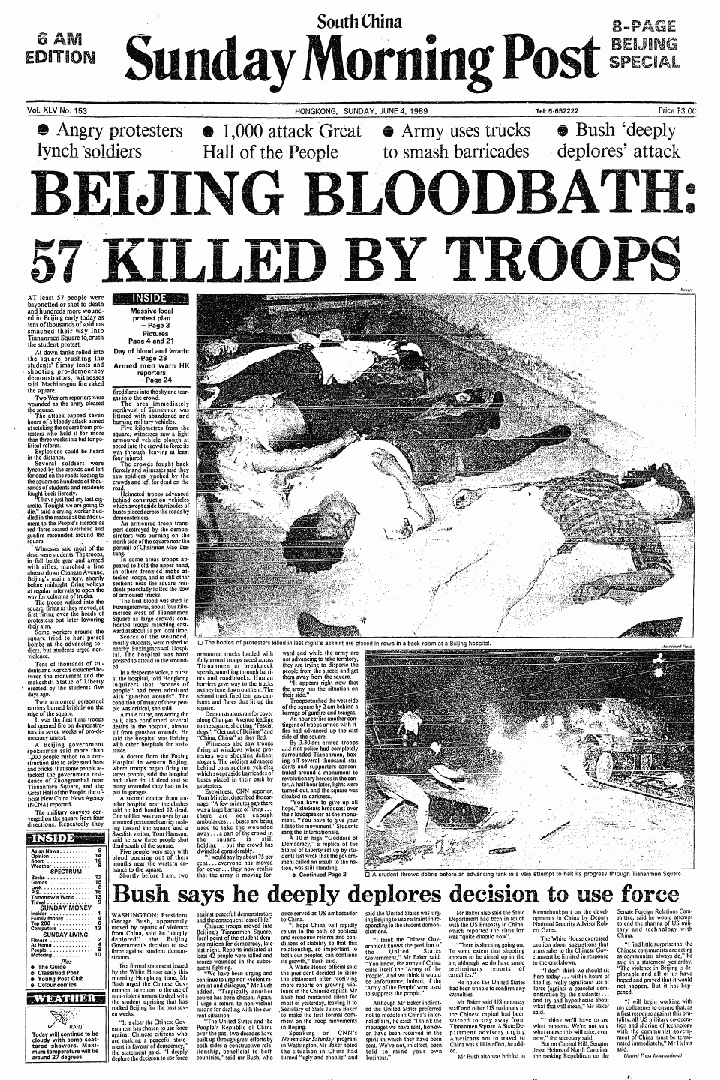

June 4 marked the 25th anniversary of a brutal military crackdown on pro-democracy protests led by students and residents in Beijing. Hundreds of people were killed and many more were wounded when People's Liberation Army units rolled into Tiananmen Square, ending more than a month of peaceful protests seeking political reforms.

In the following pages, former government officials, student leaders and other eyewitnesses revisit the momentous events of spring, 1989. These personal accounts, gathered from recent video interviews, as well as memoirs, shed new light on the hope and despair left by those days, which continue to haunt China a quarter century later.

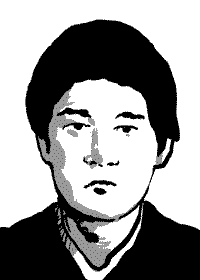

At 21, Zhou Fengsuo thought he was marching towards a bright future. “Everybody was seeking new ideas, new knowledge,” he said, 25 years later on the phone from Austin, Texas. “It was exciting to learn and discuss how life was changing for the better.”

A physics student at Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University in the late 1980s, Zhou regularly attended literary salons and discussions where academics debated China’s political future. He remembers listening to Fang Lizhi, then one of China’s most influential democracy advocates, at Peking University. Both would later be exiled to the US.

The era of debate ended when the People’s Liberation Army entered Beijing and retook Tiananmen Square by force in the early hours of June 4, 1989.

Throughout the 1980s, academics questioned Chinese culture in ways unimaginable today, with literary salons popping up everywhere, he said. “I went because I felt these were the people who would shape China’s future,” said Zhou. “There were more and more of them.”

“I went because I felt these were the people who would shape China’s future.”

Like most students, Zhou was told to watch the television series “River Elegy” produced in 1988 that encapsulated the debate at the time. Broadcast by China Central Television, the programme argued that Chinese culture was backward and oppressive, and that it needed to learn from the West to achieve modernisation. “It might have been the most important television programme that has ever been made,” said Rana Mitter, professor of Chinese history and politics at the University of Oxford. “Very few television series have sparked a political movement. These people were really serious about ‘saving’ China.”

City residents were frustrated. Food prices had been rising and society had become inured to corruption. Those well-connected to the party and government had been profiting from the “Reform and Opening Up” policy that created an economic boom with little legal oversight.

Ma Shaofang, a 25-year-old Jiangsu-native, took evening writing classes at the Beijing Film Academy. “Even the most basic fairness didn’t exist in that society at the time,” he said in a recent interview in Beijing. “We discovered that going to university wasn’t the best choice; buying and selling television sets was the best choice,” he said.

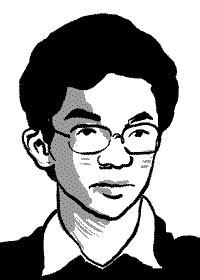

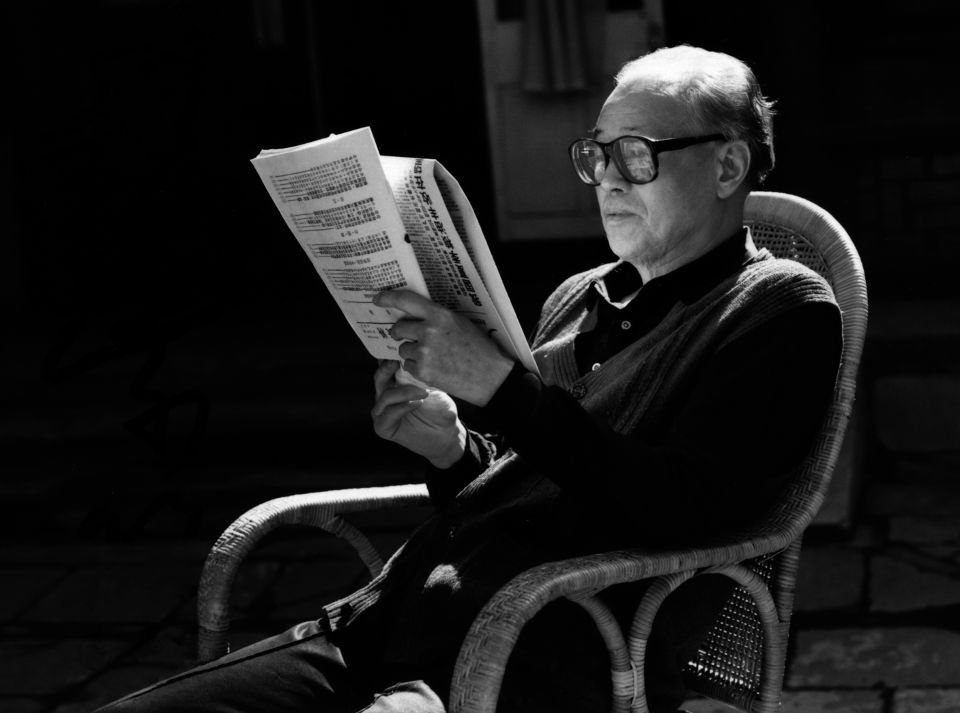

The economic reforms had started to touch the foundations of Communist Party rule, said veteran journalist and Party historian Yang Jisheng. “After the Cultural Revolution, liberal thought began to sprout,” he said. “Liberalism was an attack on one-party rule - it was the wish for democracy, the wish for rule of law, the wish for respect for the constitution.”

Yang was a reporter for the Xinhua news agency in 1989. In January that year, the state-owned news service transferred him from Tianjin to the capital. The move allowed him to witness first-hand the seismic events of the coming months. “I never had the habit of keeping a diary,” he said, but in March 1989 he started one. He had a feeling that “something big was going to happen”.

A cataclysmic chain of events began with a national news broadcast announcing the death of Hu Yaobang. The former general secretary of the Communist Party and key advocate for political reforms had suffered a heart attack during a Politburo meeting. The Party had kept his heart disease a secret, so the 73-year old's death of heart failure on April 15 came as a shock to many.

Wu Jiaxiang, a senior aide to the Communist Party’s Central Committee, was immediately informed of Hu’s death. Wu was working in the office that managed the daily affairs of the party leadership when Hu died at the Beijing Hospital. “We thought heaven was collapsing,” he recalled.

“It was hard to accept Yaobang’s death, I thought he had been wronged,” he said. Hu had been forced to resign as the party leader for supporting student protests two years earlier. “We were worried students could react badly so they immediately sent me to Peking University to investigate, but the matter had already got out of hand.”

Student Zhou was playing wuziqi, a board game, at the Tsinghua University campus when he heard the news. He also rushed to the nearby Peking University campus to see how students there were reacting to Hu’s passing. “By the time I got there, it was chaotic. People were singing the Internationale [the Communist Party anthem]. Some began hanging big-character posters,” he said, referring to handwritten political declarations. He soon wrote one himself, comparing China’s constitution with the American Declaration of Independence.

The students “were expressing their desire for advancing reforms," Hu's successor Zhao Ziyang wrote in his memoirs. "Hu had always been a proponent of reform.”

In the coming days, Zhou and his five roommates were among the hundreds of students who carried wreaths of flowers to Tiananmen Square.

“Hu Yaobang had always been a proponent of reform.”

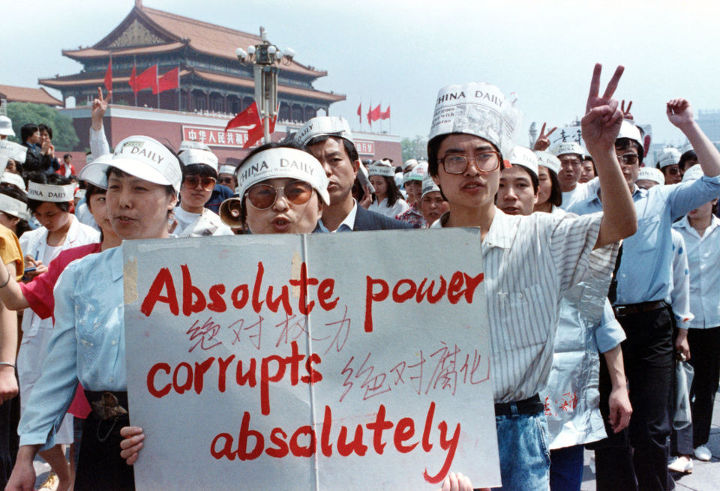

Zhou, like many others, gave his first speech on the square. “As we marched to the square, we would try to rally support by yelling slogans like ‘We want freedom of the press!’,” recalled Zhou. “But then someone said you must yell ‘Fight corruption!’ to get better resonance with the crowd and so we did. It worked.”

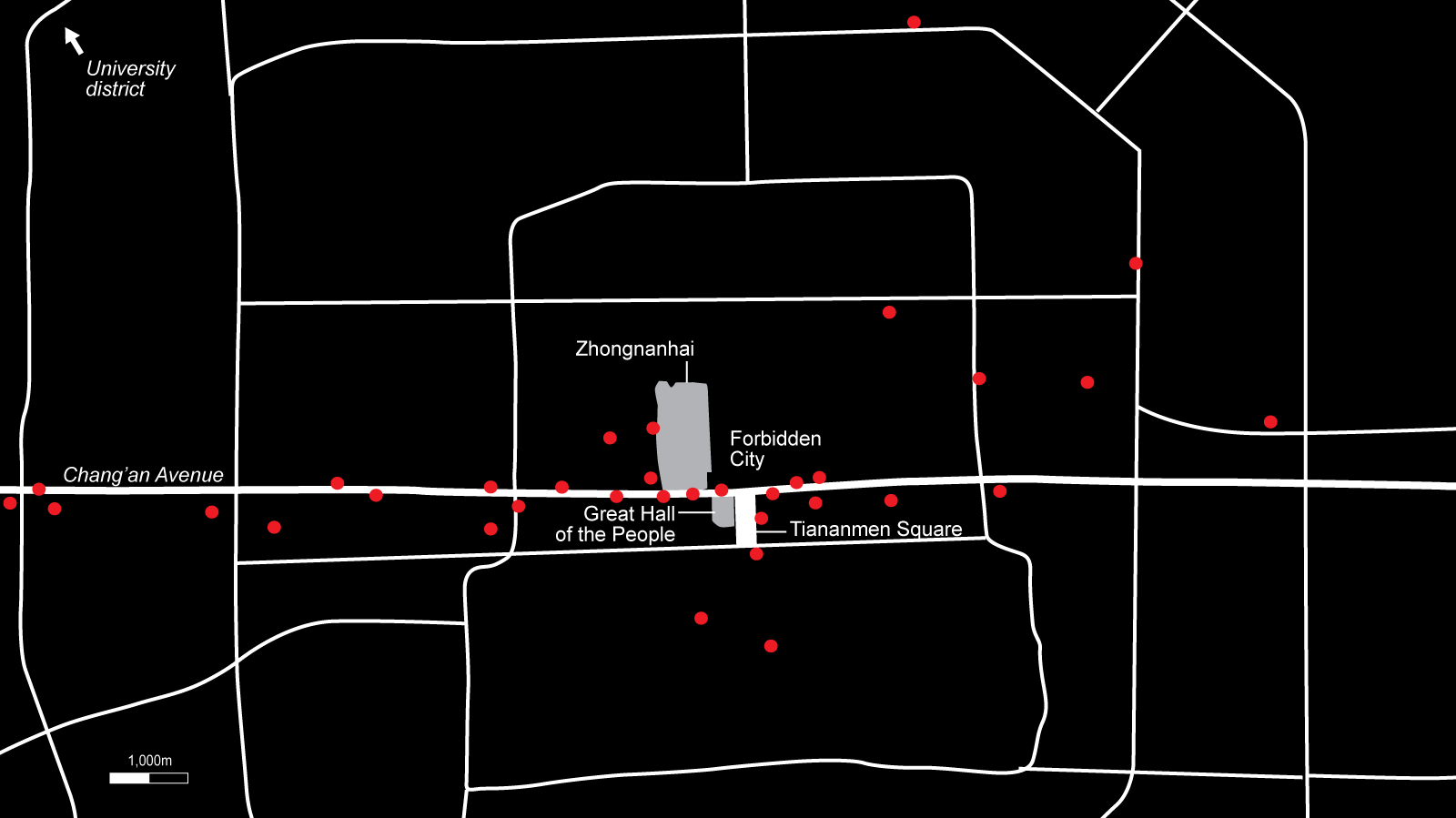

The students drafted a petition to the government. Among their seven demands were the abolition of censorship and the declaration of assets by Party leaders and their families. On the evening of April 18, about 2,000 demonstrators gathered outside the nearby the main gate of Zhongnanhai, the Communist Party leadership compound, to convey these demands, all of which went ignored.

Students also took to the streets in Nanjing, Wuhan and Shanghai, Xinhua reported internally, according to the memoirs of Zhang Wanshu, who was then a senior editor with the news agency’s domestic news department.

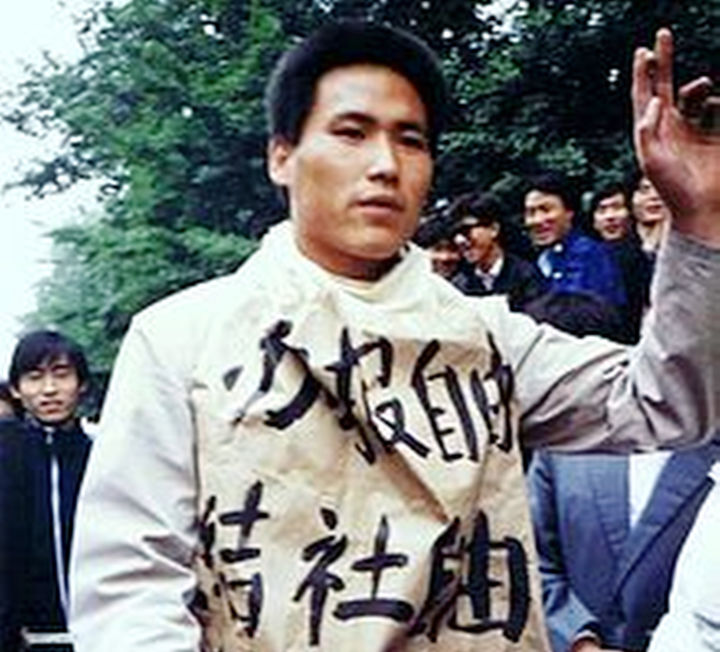

By April 20, independent student unions started to spring up on university campuses. Feng Congde, one of the seven students who set up the first such group at Peking University, said their demands did not challenge the Communist Party’s rule. "At that moment, we only called for freedom of association and freedom of speech within university campuses," said Feng, now in exile.

Hu’s memorial service took place as scheduled a week after his passing, on April 22. Inside the sombre Great Hall of the People, some 4,000 Party leaders commemorated the former Party leader. Hu “was brave enough [...] to insist upon what he thought was right”, Zhao said in his eulogy.

Outside the hall, a crowd of tens of thousands of people defied a police order to disperse.

“The students chanted pro-democracy slogans over the heads of soldiers and police at government leaders as they entered the hall,” reported the South China Morning Post at the time, adding that the gathering was the biggest of its kind since the founding of the People’s Republic 40 years earlier.

For Zhou, the rally was life-changing. “At that time, I realised there was a desire among students to unite for a reason,” he said. Three students knelt down in front of the Great Hall of the People to convey their petition demanding a re-appraisal of Hu’s life. Again, their petition went ignored.

On April 23, 1989, Communist Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang left for a long-scheduled state visit to North Korea. In a last private meeting with paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, Zhao had called for a conciliatory approach to the protests and thought he was in agreement with Deng, he recalled in his memoirs.

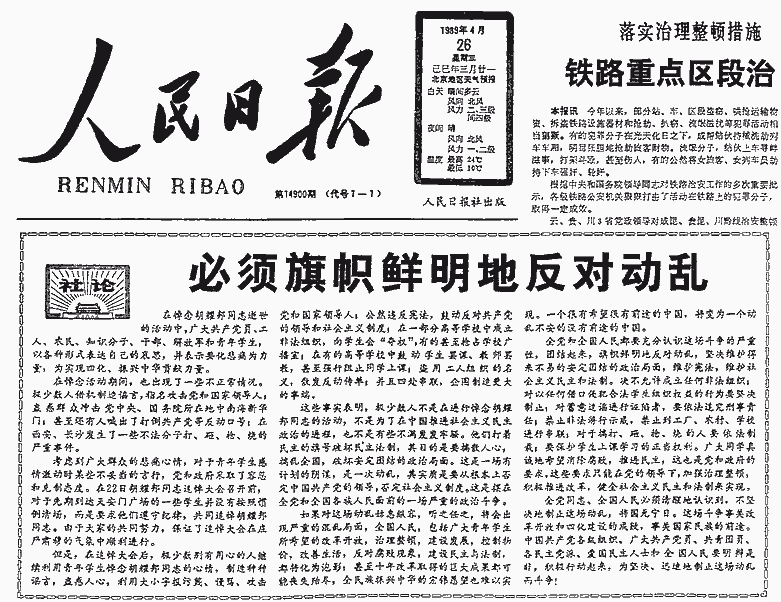

In the days of his absence, the position of the Communist Party’s top leaders towards the student movement remained unclear. There are conflicting accounts on what meetings took place among the senior leaders left in Beijing. On April 26, the party’s top newspaper, the People’s Daily, ended that uncertainty by denouncing the student movement in a front-page editorial, indicating that the leadership had decided not to tolerate the student movement any longer.

“We must unequivocally oppose turmoil,” it said. “An extremely small number of people with ulterior motives continued to take advantage of the young students’ feelings of grief for Comrade Hu Yaobang to create all kinds of rumours.”

For Bao Tong, Zhao’s secretary, the reformist’s departure had been fatal. “Deng Xiaoping was fully playing both sides,” he said. Bao, who also served as the director of the Party’s Office of Political Reform, would later become the most senior government official to be jailed after the June 4 crackdown.

Many students saw the editorial as a sign that the leadership would not accept their demands, said historian Yang Jisheng. The editorial’s tone also reminded their parents of the terror of the Cultural Revolution they had lived through in their youth, he said.

By Zhao’s return on April 30, about 70 per cent of Beijing’s 130,000 students stopped attending classes.

More than 100,000 people took to Beijing’s streets the following day. Worried about a crackdown, many wrote their final wills, but police caved in and let the students return peacefully to Tiananmen Square. By Zhao’s return on April 30, about 70 per cent of Beijing’s 130,000 students stopped attending classes. Students had already set up an autonomous student union to coordinate their movement across campuses.

But Zhao had already lost the fight within the Party leadership to conservatives, said Bao. “When he returned, he kept asking to meet Deng Xiaoping,” he said. “[Deng’s] secretary said he couldn’t, that [Deng’s] health wouldn’t allow it.” They only met again in the presence of President Yang Shangkun on May 13. “What was Deng doing in these 13 days?” wondered Bao, looking back 25 years later. “I think he was preparing the troops.”

As Zhao returned from Pyongyang, a sensitive day was approaching. May 4 marked the 70th anniversary of the student protests in Beijing of 1919, a founding moment for the Communist Party.

Zhao and many reformists thought history was repeating itself, said Rana Mitter, author of Bitter Revolution: China’s struggle with the modern world. “For people around Zhao, reforming faster was the appropriate response,” he said. “Hardliners drew a different parallel: to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. They did not see the movement as the same celebration of individual free-thinking.”

Disagreements within the party had become visible. In Zhao’s absence, the hardliners had called the movement “turmoil”. Government spokesman Yuan Mu, however, told foreign journalists that “black hands” or agitators were behind the movement. Zhao praised the spirit of the 1919 student movement in a speech a day ahead of the anniversary. The following day, he publicly vowed that the government would engage in dialogue, a key demand of the protesters.

After neat rows of cadres celebrated the anniversary in Tiananmen Square, students again marched in from the universities to the square. The next day, some 80 per cent of students returned to their classes, the Xinhua news agency reported. But student leaders did not give up on their demands. Representatives of 24 independent student unions submitted a petition asking for real dialogue regarding their earlier requests. On May 9, 1,013 journalists signed an open letter making similar demands.

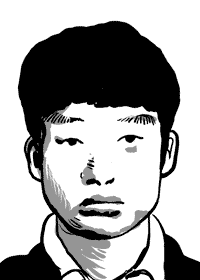

In the days of Zhao’s absence, students established citywide organisations as student leaders started to emerge, recalled Ma Shaofang, who became one of them.

Others included Wang Dan, a 20-year-old history major at Peking University who had already distinguished himself in student circles as a political activist. Wang would become China’s most wanted man after the crackdown. Wuer Kaixi, later the second most wanted, had gained prominence as one of the first students beaten by police. He was among the first to rally the students after the People’s Daily’s April 26 editorial, recalled Ma.

At the first protest gathering, Ma, a Beijing Normal University student, “took a bicycle and a loudspeaker to organise the chaotic crowd and they started moving” towards Tiananmen Square.

By the time the anniversary of May 4 had passed, most students had returned to class. Student leaders were running out of options, said Ma.

“The students started out with five cards they could have played: demonstrate, go on strike, stage a sit-in, go on a hunger strike, or attend nationwide rallies,” he said. “We only had one card left in our hand, and that was a hunger strike. Playing that card would decide who won the game.”

Then-President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev was expected in Beijing in less than two weeks. The architect of perestroika and glasnost, political and economic reforms, Gorbachev was the first Soviet leader to visit China since 1959. A hunger strike at Tiananmen Square would embarrass China’s leaders into a dialogue, the students thought.

A small group that included Ma, Wang, and Wuer Kaixi became proponents of the hunger strike. Chai Ling, a 23-year-old psychology student from Beijing Normal University, rose to prominence by convincing several students to join the group. The group disregarded dissent among representatives of other universities in the newly formed independent student union and began their non-violent resistance and set up a “hunger strike command centre” on May 15. Estimates of how many students fasted initially varied between one and two hundred.

By the time Gorbachev arrived, about 2,300 students were on a hunger strike in the square, surrounded by the 100,000-strong crowd.

The next day, hundreds more students joined the hunger strike. By that night, some 100,000 people returned to the square in solidarity. Students from Tianjin universities had also joined the crowd. By the time Gorbachev arrived, about 2,300 students were on a hunger strike in the square, surrounded by the 100,000-strong crowd. A last-minute dialogue between the government and student leaders ahead of Gorbachev's arrival collapsed over a disagreement on whether it should be broadcast live on television. Embarrassed leaders hastily arranged a welcome ceremony at Beijing's airport. There was no red carpet.

The day after Gorbachev arrived, Ma collapsed. He had been on hunger strike for three days.

When Ma returned from the hospital, a million people were on the square, according to an estimate in the Beijing Youth Daily that had the headline “The People Build Democracy” on its front page. Censors stopped working as journalists and government employees joined the sit-in.

Cui Jian, China’s most famous rock singer, performed on the square. Hospitals provided medical treatment for hunger strikers.

Between May 16 and 19, about 60,000 students from all over China arrived in the capital on 165 trains, Zhang Wanshu, then head of Xinhua’s national news desk, recalled in his records, citing a railway official at the time. Factory owners paid for train tickets so their employees could join the protests in Beijing. Students demonstrated throughout the country.

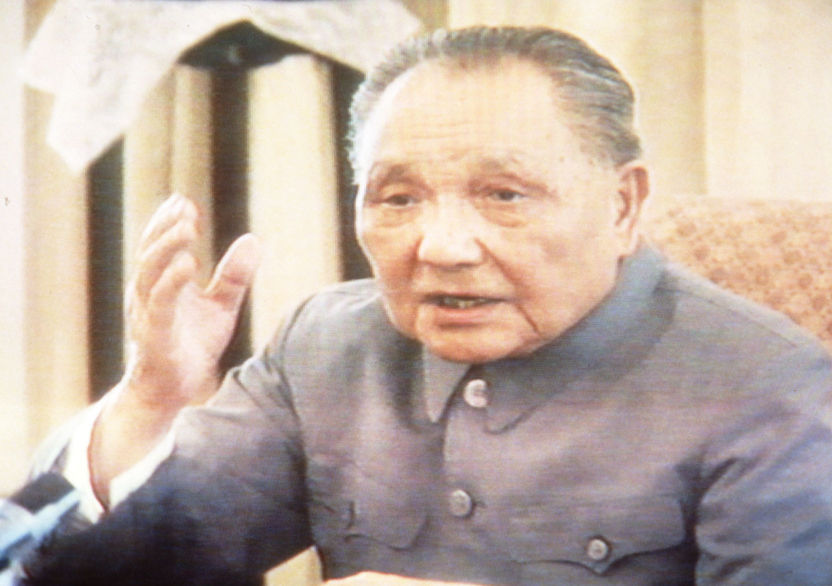

On May 17, Deng Xiaoping met with top party leaders at his home, where according to various accounts they discussed how to bring an end to the student movement. Party general secretary Zhao Ziyang argued for a lenient approach, he wrote in his memoirs. According to Deng’s biographer Ezra Vogel, the paramount leader concluded that the police in Beijing were insufficient to restore order and decided to call in the troops. Premier Li Peng and Vice Premier Yao Yilin voiced immediate support for Deng’s views, Vogel wrote.

On the following day, a defeated Zhao visited the hospitalised hunger strikers. Premier Li Peng met with student leaders including Wang Dan and Wuer Kaixi at the Great Hall of the People. It was the highest level meeting the students had achieved so far. The premier did not mention the decision to impose martial law. “I guess that the oldest of you is about 22 or 23. My youngest child is even older than you.” he told them, calling on them to end the hunger strike. “We look at you as if you were our own children, our own flesh and blood.”

Li was interrupted several times by the students. “The current movement is no longer simply a student movement, it has become a democratic movement,” Wang Zhixin, a student at the University of Political Science and Law, told him. “Beijing has been in a state of anarchy. I hope you students will think for a moment what consequences might have been brought about by this situation,” the premier said in response.

In the early hours of May 19, Zhao visited Tiananmen Square. Zhao looked tired, strikingly different to when he was last publicly seen at his meeting with Gorbachev three days earlier. “We have come too late,” he said, speaking to the students among chants. He then called on them to stop the hunger strike. However in retrospect, he later said he knew that even an end to the hunger strike would not have averted the crackdown, he wrote in his memoirs. “It would not matter if the hunger strike continued or if some people died; [the elder Party leaders] would not be moved.” It was his last public appearance before he would disappear under house arrest.

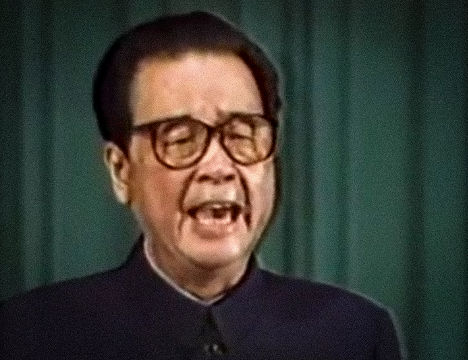

At 10pm, Premier Li declared martial law in the city during a televised speech. "The People’s Republic of China is facing a grave threat to its future and destiny,” he declared. The plan had already been leaked by sympathetic government officials in the afternoon and students had ended their hunger strike.

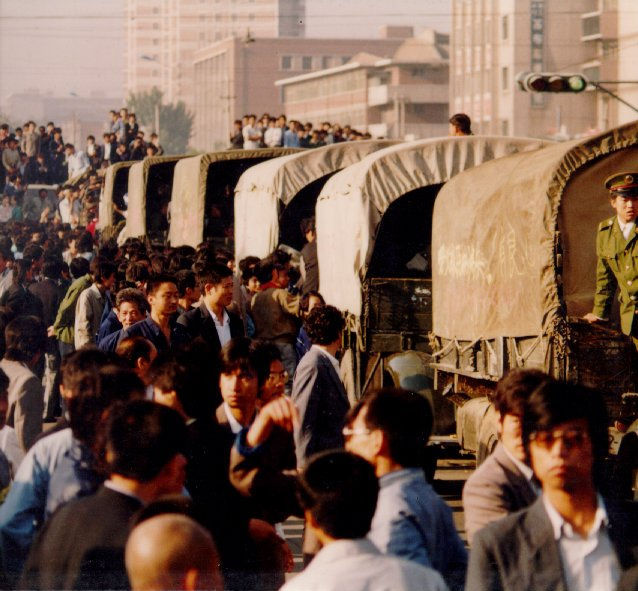

Armed troops entered the city the following day to enforce martial law, but they were stopped by an overwhelming crowd of demonstrators. "People lay on the streets to stop the troops,” said student leader Zhou. “Many brought their families, their kids to show that the protest was peaceful.”

“You had virtually the whole of Beijing and people inside the government, even writers at the People’s Daily, sympathising with the demonstrators.”

Zhao Ziyang in his memoirs recalled that Deng Xiaoping decided in a meeting on May 20, the day martial law was imposed, to remove Zhao as party general secretary. The reformist leader said he felt suddenly isolated. “Nobody actually told me that I had been removed from my position,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Of course, nobody contacted me on any work-related issues either.” His secretary Bao Tong was among the first to disappear before the military crackdown.

For Perry Link, an American professor of Chinese language and literature who was in Beijing during the protests, it was the massive scale of the demonstrations that led Deng to his decision. “You had virtually the whole of Beijing and people inside the government, even writers at the People’s Daily, sympathising with the demonstrators, not just in Beijing, but virtually in every provincial capital,” he said.

Many students returned to their classes in late May. But the confrontation between those who remained on the square and the government became more intense. Further requests for dialogue by the students went ignored. Troops were sent in from outside Beijing.

One junior cadet at the time said his year of field training was interrupted by orders to travel to Beijing. “We only had two hours of electricity [each day] at our training camp,” he said. “We had no idea what was happening in Beijing.” When he arrived at Beijing railway station, civilians surrounded him. “‘Don’t suppress the movement,’ they said, but I had no idea what they were talking about,” he recalled. The next day he visited the square and was taken aback. “They were demanding change, and even though we didn’t know what that meant, we thought change was beautiful,” he said.

By May 24, student leaders on hunger strike set up the “Defend Tiananmen Square” headquarters with student leader Chai Ling in command. Workers, among them Han Dongfang, set up an independent labour union on the square. The demonstrators vowed to stay put until June 20, when the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress was scheduled to hold a meeting. Some even demanded the ouster of Premier Li Peng. The students eventually ended the hunger strike but radical slogans like “oppose military dictatorship!”, “Down with Deng Xiaoping, down with Li Peng” became more widespread.

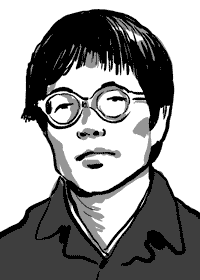

Zhou Duo, one of the leading intellectuals supportive of the student movement, recalled he worried that bloodshed was imminent. He was among those within the party who had been first informed that its conservative wing had prevailed to impose martial law.

On May 28, the prominent writer and Zhou’s friend Liu Xiaobo suggested another hunger strike to turn the situation around. They had met two years earlier when Liu gave a lecture at the electronics company Zhou worked at, and had quickly become good friends. “It’s like when your best friends try to drag you along to something that could lead to jail and beheading,” He hesitated to go along with Liu’s suggestion, he said, but was ultimately convinced. Given their prominence, the party leadership would not dare to send in troops, the pair reasoned.

Two more well-known participants raised their profile even further. On May 30, Zhou and Liu were joined by Hou Dejian, a Taiwanese singer and songwriter who had moved to mainland China in the early 1980s and become wildly popular among young students. Together with Gao Xin, a journalist and Communist Party member, they on June 2 declared a new hunger strike.

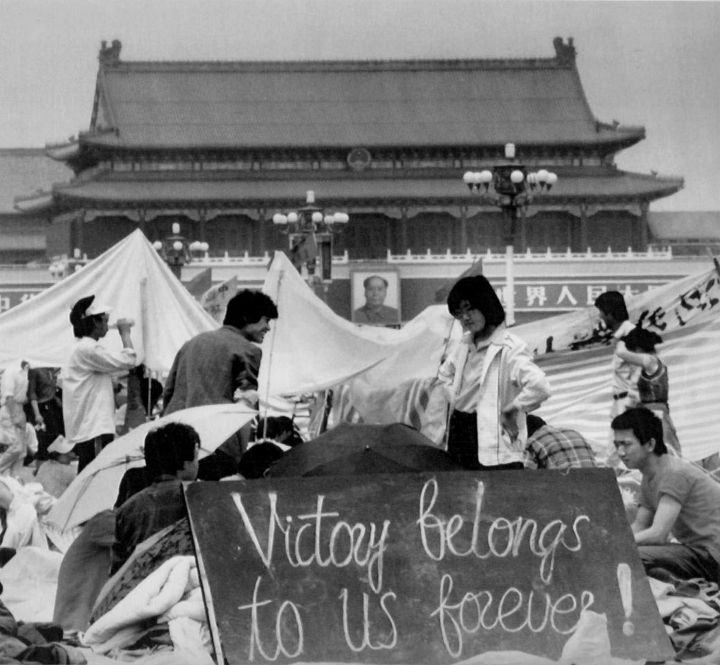

Some 530 tents and about 1,500 students were left still demonstrating on the square.

We “take action to protest against martial law, to appeal for the birth of a new political culture,” they wrote in a hastily penned declaration, printing 200 copies. They settled in a tent and waited.

Art students had rolled the Goddess of Democracy, a replica of New York’s Statue of Liberty about 10 metres tall, onto the square. Some 530 tents and about 1,500 students were left still demonstrating on the square. By the evening of June 2, Zhou Duo remembered stepping out of the tent. “When I left the tent, the scene was like that of Mao inspecting the Red Guards.” Music legend Hou Dejian sang on the square, Zhou remembered.

A day earlier, troops had already been seen setting up camp nearby. The government instituted a ban on unauthorised foreign media coverage. Members of the military and government were informed to stay away from Tiananmen Square.

On May 14, 1989, the liberal academic Chen Ziming was in a meeting at the Economics Weekly magazine when a car from the Communist Party Central Committee arrived. An employee of the Central Committee’s United Front Department asked him and his colleagues to get in.

Chen was by then a well-known advocate of political reform. The co-founder of the Beijing Social and Economic Research Institute, China’s first independent political think tank, said he had chosen to stay away from the movement to avoid making the protests look orchestrated.

Now, however, the Director of the Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, Yan Mingfu, conveyed a request to him to stop the students’ hunger strike. “We’ve heard that you have a way to talk to the student leaders, can you go see them?” he recalled the party cadre’s asking him. “We want to talk to the students, but we don’t know who to talk to.”

The eleven members of Chen’s institute voted on whether they should intervene and seven voted for it. Chen himself voted against getting involved, but accepted the majority decision. Chen said he saw his role then to be a rational voice mediating between the Party and protestors towards not only a peaceful resolution of the standoff but also progress in China’s political reform.

However, he was arrested in October 1989, four months after the military crackdown, and later sentenced to 13 years in prison for “counterrevolutionary incitement and conspiracy to subvert the government”. His think tank was closed.

State media accused Chen of being a “black hand”, a key orchestrator who merely exploited the students’ good intentions. Chen’s case became a key element in the Party’s narrative after the crackdown: that the movement was not spontaneous, but orchestrated by vicious political forces seeking to overthrow the Communist Party.

On the afternoon of May 27, 1989, Major General Xu Qinxian made the most important decision of his life. The commander of the People’s Liberation Army’s 38th Army Group defied the order to impose martial law in Beijing. His court martial, the only documented case of a senior commander questioning the morality of the Tiananmen crackdown, led to a five-year prison sentence and house arrest.

“I told them this is not a war, this is a political incident and political incidents cannot be handled this way,” he said in an interview transcript smuggled out of his home in central China, where he is currently living under surveillance. He remembered saying: “It will be impossible to avoid clashes. It is impossible to tell good and bad apart in clashes with civilians - who will be responsible for this?”

Xu’s troops had already maintained security while unarmed during the Hu Yaobang memorial in April and later protests. Martial law imposed on May 20 was not enforced due to massive peaceful resistance in the capital. But by May 27, the political commissar of the Beijing Military Region Liu Zhifa gave Xu the order to enforce martial law by any means necessary. Xu first insisted on a written order. Once that written order was forwarded, he remembered saying: “I disagree. I will not participate in whatever happens next.” He returned to the military hospital where he received treatment for a bladder stone. He was then relieved of his command on May 27 and detained in a warehouse in Mentougou in the western outskirts of Beijing until the end of the year. He was formally arrested, court-martialled and sentenced to five years in prison.

Xu said he wasn’t the only commander to disagree with the order. Major General He Yanran, commander of the 28th Group Army, and Major General Zhang Mingchun, political commissar of the same group, both obeyed the order but delayed its enforcement, he said. “They looked for many excuses to not advance to Tiananmen, but they never admitted their refusal to comply.” Both He and Zhang continued their careers in the People’s Liberation Army. Zhang died in 1994, while He lives in a military retirement home in Shanghai.

“It will be impossible to avoid clashes. It is impossible to tell good and bad apart in clashes with civilians - who will be responsible for this?”

Xu now lives with his wife in Shijiazhuang, the capital of Hebei province. The 79-year-old remains barred from visiting Beijing.

He said he did not regret his decision. “Despite ten years of Cultural Revolution, the people still had hope in the Communist Party.” he said. “Should we have destroyed that little bit of hope that was left?”

“They thought I had conspired with General Secretary Zhao Ziyang,” he said. “In fact, things were much more simple. There was no underground activity, no plot, no outside activity - it was fully my own action.”

Xu had spent his whole adult life in the People’s Liberation Army. As a young volunteer, he fought US troops in North Korea in the 1950s. “I love the Communist Party, I want to protect it,” he said when he disagreed with the martial law order.

He wasn’t the only one. On May 23, six retired generals and an admiral signed a joint open letter opposing martial law. “The PLA belongs to the people,” the letter read. “It should not confront the people, much less suppress them. Most importantly, it will not fire on the people.”

Between 10,000 and 15,000 helmeted, armed troops moved towards Beijing in the late afternoon of June 3, the US embassy reported in a late night cable revealed by Wikileaks decades later. “Elite airborne troops are moving from the south and tank units have been alerted to move,” it read. “Their large numbers, the fact that they are helmeted, and the automatic weapons they are carrying suggest that the force option is real,” it concluded.

Hunger striker Zhou Duo first heard of troops moving in from sympathetic soldiers. “The two of them, brothers from within the military, put on civilian clothes, sneaked onto the square and went to the hunger strikers’ tent,” he recalled. “They told me ‘this evening, something big is going to happen.’”

Zhou said he pondered leaving the square, but decided against it. “If I left, it would have been like treason - I couldn’t have possibly done such a thing,” he said. “There was nothing we could do except embrace our fate.”

In the afternoon, troops used tear gas in Liubukou, just a kilometre west of the square. “They began to advance, and around 10 or 11pm shots were heard on all sides, mostly from Muxidi [some five kilometres west of Tiananmen square]. Gunfire became more and more intense, like New Year firecrackers, and we were all frozen in shock,” recalled Zhou. At the time the students at the square still thought the military was using rubber bullets, he said. “We didn’t think they would use real bullets.”

The last demonstrators gathered around the Monument to the People’s Heroes, the obelisk at the centre of Tiananmen Square, as troops surrounded them. “A student asked us for our last words and beautifully wrote them down,” said Zhou Fengsuo, one of the students on the square.

Zhou Duo and Hou Dejian approached the soldiers that surrounded them and negotiated an exit route for the several hundred students to leave the square. They left peacefully.

Zhou, who said he was hit by soldiers as he left, grabbed his bicycle and cycled back to his dormitory. On the way, he stopped by Fuxing Hospital, where he saw more than thirty dead bodies lying outside.

Another student who was among the last to leave the square was Fang Zheng, a 22-year-old from Hainan at the Beijing Sport University. He was walking on Changan Avenue on his way from Tiananmen Square to his campus when a row of tanks charged at the students, he recalled. “They had already taken the square. To this day I don’t know why they targeted us.”

A young woman walking nearby fainted. He managed to push her up and over a metal fence to get her out of the tanks’ path. A tank wheel clipped him. He woke up the next day at a hospital. Both legs were gone. “We later learnt that nine people had been crushed to death by the tanks and five more had been wounded in the incident,” he said. He continued his career in sport as a wheelchair athlete after the crackdown and emigrated in 2009 to the US. He now lives in San Francisco.

Senior party official Li Rui was at home with his wife when he started hearing gunfire on June 3. “The two of us stood at the balcony watching [the soldiers] pass by,” he recalled. “I remember saying: ‘these rifles can’t shoot us, we’re too far away,’.” Li still lives near the same crossroads at Changan Avenue, some seven kilometres west of Tiananmen Square. “We were shouting slogans,” Zhang Yuzhen, Li’s wife, recalled. “‘You group of bastards are beating up good people,’ we shouted. Everyone was furious.”

Later that same evening, Guan Shanfu, a senior prosecutor who lived in another building, visited Li to tell him that his son-in-law had been shot dead, Li recalled. “Guan’s son-in-law was boiling water in the kitchen when he was shot,” he said. “[Guan] showed me the bullet, it was an expanding bullet. An imported dumdum bullet shot this man dead.”

Li, now 97, was an early member of the Communist Party. He served as one of Mao’s secretaries in the early years of the People’s Republic before he was ousted and jailed for his criticism of Mao’s frenzied push for industrialisation that led to mass starvation in the late 1950s.

After Mao’s death, he was rehabilitated under paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and became an adviser to the Party leadership. “What happened on June 4 was one of the Communist Party’s biggest mistakes,” he said.

On the morning of June 4, Li and his wife discovered that a neighbour’s maid had also been killed overnight. On Changan Avenue, they found abandoned tanks and climbed on top of one to see a line of wrecked tanks. “They had not driven to Tiananmen, and dozens of armoured vehicles had been discarded,” he said. For Li, it was a sign that some soldiers had refused to force their way further towards the square. “Many of them threw their rifles into the canal,” he said. “This meant these troops were remarkable - they did not take part in this.”

Thousands of others did. Gunfire could be heard for several days in the capital. On June 4, the PLA Daily, the mouthpiece of the armed forces, said a “severe counterrevolutionary riot” had occurred in the capital the previous day. “Since the founding of the republic there have never been such horrendous riots in the capital,” it read.

Five days later, Deng Xiaoping made his first public appearance after the crackdown, meeting senior PLA officers along with senior party elders. In his televised speech, he called the democracy movement a “political storm” that had to happen sooner or later and had to be stopped for the benefit of long-term stability.

| Organisation | Date | Killed | Wounded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Associated Press | June 5, 1989 | At least 500 | - |

| Beijing Independent Student Union | June 5, 1989 | 4,000 | - |

| State Council spokesman Yuan Mu at press conference | June 6, 1989 | Less than 300 in total including 23 university students in Beijing | 5,000 troops, 2,000 civilians |

| Chinese Red Cross staffer estimate | June 1989 | 727 of which 14 military and 713 civilian | - |

| South China Morning Post | June 6, 1989 | 1,400 feared dead | 10,000 |

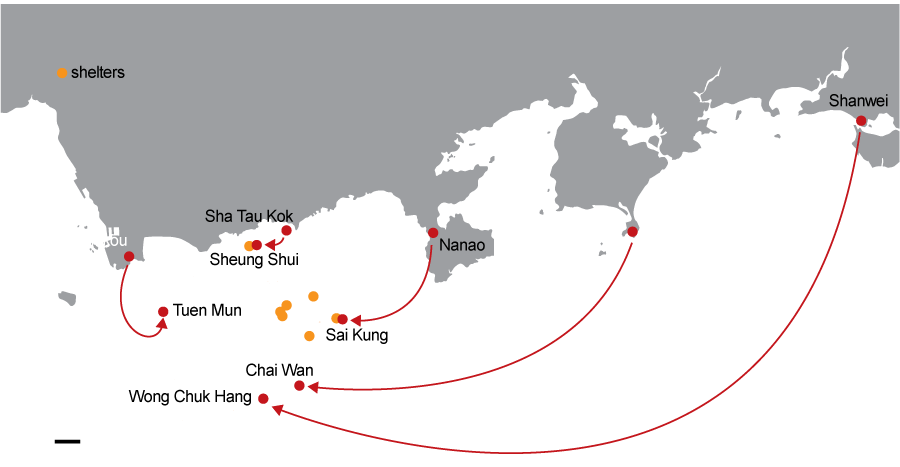

In Shenzhen, a dried seafood merchant received an odd request: Could he hide some people in his warehouse? Thus began the Hong Kong man’s involvement in a many-year effort to get some of the most wanted Tiananmen protesters out of mainland China.

“At first, I just wanted to help out a little bit,” said the man, who asked that he be identified only by the nickname Tiger. “Then I was told to stay because there was no one else to help out.” He soon paid triad gangs to smuggle the students to Hong Kong and housed them in a hideout near Ma On Shan.

Known by the operation’s code name “Operation Yellow Bird”, Hong Kong sympathisers like Tiger and triad smugglers were instrumental in securing freedom for 10 of the 21 most wanted student leaders and hundreds of others, including Yan Jiaqi, a senior adviser to purged Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang.

Much of the operation is still shrouded in mystery. It was organised and financed by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, the movement that later organised the annual vigils and set up the SAR’s only Tiananmen Museum in April this year.

A Newsweek article in 1996 recounted the audacity of the operation. “On at least five occasions, ‘extraction’ teams were sent into China to find and rescue top dissidents. They were equipped with scrambler devices, night-vision goggles, infrared signalers, even makeup artists to help disguise the fugitives.”

Tiger used donations channeled through the Alliance to pay off the smugglers, who – from fear they might raise their charges – were not informed of who their passengers were. He organised safe passage for 20 of the 200 people who managed to escape to Hong Kong in Operation Yellow Bird. Freedom from prosecution in the mainland cost on average between HK$40,000 and HK$50,000 in donations. At least two people were jailed in China for the assistance they provided to the fleeing movement leaders.

Longtime rights activists like Szeto Wah and Reverend Chu Yiu-ming were among those in the Alliance to raise funds and organise shelter - first in hotels, then in secluded hide-outs and private homes. Chu banned the students from smoking, drinking and affairs, recalled Tiger. “It was tough to ban writers and artists from smoking and drinking,” he said. “I secretly gave them what they needed.”

British intelligence and French consular officials assisted the Alliance in moving the refugees as quietly as possible past immigration at Kai Tak airport and the press to France, from where many would travel on to the United States.

By 1997, the year Hong Kong was returned to China, the last refugees and key operatives hurried to leave the territory. Tiger and Chu temporarily moved to the US, but soon returned and have lived here since.

Chu is now a leading organiser for the Occupy Central movement, which demands universal suffrage in the chief executive election in 2017. “Don’t keep telling me that democracy has to be implemented in a ‘gradual and steady’ approach,” the now 70-year-old told the South China Morning Post last year. “I am now calling for universal suffrage by 2017.”

Ma Shaofang said he left the square with the last students. He had stayed until the sun rose on June 4, and gunfire continued. On his way back to the Beijing Film Academy, he passed by Deshengmen, one of the city’s old gates. The dead body of a nine-year-old child was lying on a handcart. “Everyone was in a rage, and the soldiers didn’t dare to raise their heads,” he said. Two days later, he was still in Beijing. “Another film academy student asked me why I was still there,” he recalled. “He said: ‘You better run’. I said nothing will happen.”

Twenty-one of the student leaders were soon declared the nation’s most wanted, with Ma ranked number 10. Within a week, at least 400 people had been detained, state media said. China Central Television aired footage showing soldiers escorting detained men at gunpoint and Premier Li praising the troops.

Ma was detained in Guangzhou a week after the crackdown. He was sentenced to three years in prison on charges of “counter-revolutionary incitement”. He was released in 1992, and now lives in Shenzhen.

Among the 21 most wanted, six, including Wuer Kaixi and Chai Ling, managed to flee China via Hong Kong. Hong Kong and mainland sympathisers bribed and smuggled their way out of China in Operation Yellow Bird. Wuer Kaixi now lives in Taiwan, and has been repeatedly refused entry into Hong Kong and Macau. Chai lives in the US.

The 14 others, including Wang Dan and Zhou Fengsuo, were detained along with hundreds of others. Zhou and Wang both spent time in jail until they were allowed to leave into exile in the US in 1995 and 1998 respectively. Zhou now lives in Austin, Texas, while Wang is a university lecturer in Taiwan.

Zhang Boli, the number 12 most wanted, was detained in Russia and repatriated. He spent two years in hiding and finally escaped to Hong Kong in June 1991. He is now a pastor in Virginia.

Among the thousands who were detained after the PLA retook Tiananmen Square, at least 20 people were executed, according to the US-based Dui Hua Foundation. The legal rights watchdog estimates that 1,600 went to prison. Jiang Yaqun, the last person known to be incarcerated for “counter-revolutionary crimes,” was released sometime in 2012. Others could still be in prison.

Mass rallies calling for freedom of speech did not return to China. In 1998, at least four of the nine most wanted students still left in China became members of the Democratic Party of China, for which they were soon detained.

Zhao Ziyang spent the rest of his life under house arrest. He was eventually allowed to travel to the provinces, but up until his death in 2005 never allowed to appear in public. His secretary Bao Tong became the highest-ranking official to be sentenced to prison, and served seven years for “revealing state secrets” and “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement”. He has since lived under surveillance in Beijing. Leading dissident Fang Lizhi and his wife spent a year in the US embassy before they were allowed to leave for the US.

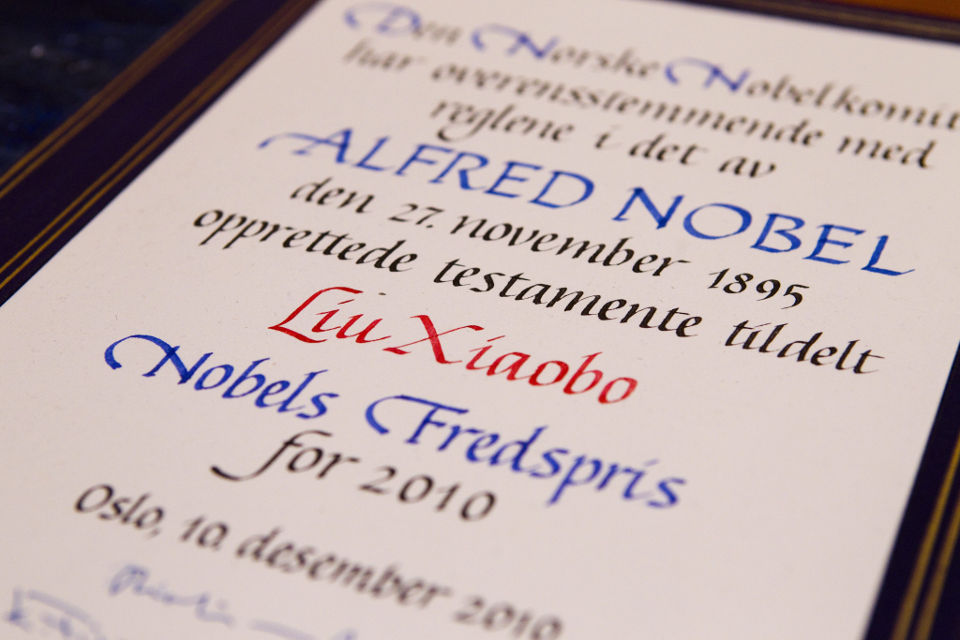

Hunger striker Liu Xiaobo was among the first to be detained after the crackdown. After 19 months of detention, he was found guilty of “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement” but his sentence wasn’t enforced due to his contribution to ending the stand-off on Tiananmen Square peacefully. He is now in his fourth year of an 11-year jail sentence on charges of “inciting subversion of state power” for initiating the Charter 08 manifesto, which reiterated the students’ calls for democracy and free speech from 1989. Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 2010.

Teng Biao, now a visiting scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, was 15 during the Tiananmen crackdown. He only learnt what happened once he went to university. “Political silence has become almost universal,” he said. “It was such a great shock at the time, but the fear from then has transformed into disdain.”

“Political silence has become almost universal.”

The majority of China’s population has lost all hope in political reform from within the system, said Teng, a participant in the New Citizen Movement, which has called for government transparency and the respect of human rights over the last years. “The elite has no incentive to change the system,” he said.

The New Citizen Movement called on the government to respect constitutionally guaranteed rights, enforce transparency of officials’ assets and equal access to education. Its founder Xu Zhiyong was sentenced to four years in prison in January on charges of “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order”.

Teng said that grassroots advocates for political reform have changed their strategies. “Citizens have used concrete cases to raise their political demands and win the public’s trust,” he said.

“They have moved from abstract demands like democracy, they have moved to issues that are closer to the hearts of the wider public, like the environment, birth control and education.” Even though the number of people who stood up to make such demands was small, “[activist] groups like the Southern Street movement expand the space for the rest of society,” he said.

“At the time, the students kneeled down outside the Great Hall of the People asking for rights,” he said. “We don’t ask anymore - we demand these rights as citizens.”

The terror of those June days continue to haunt Chinese society, even as some citizens try to commemorate those whose lives ended near the square.

Beijing police in April detained veteran journalist Gao Yu for "leaking state secrets" just one day before she was expected to attend a meeting of prominent intellectuals discussing the Tiananmen anniversary. Gao had been arrested on June 3, 1989 and jailed for a year after writing about the Tiananmen protests.

In early May, well-known human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, who had taken part in the student movement 25 years ago, was detained by Beijing police on suspicion of picking quarrels and provoking trouble. Pu was one of 15 people who met at a private home in Beijing to discuss the Tiananmen legacy.

Xu Youyu, a political scientist and historian was also detained after participating in the same seminar. In a 2012 lecture in Australia, reflecting on the Tiananmen movement, he said that China's intellectuals had missed an opportunity in 1989 to bring about political reforms.

"Chinese intellectuals were not prepared for any social movement or social transformation in the 1980s," he said. "They failed to give any practical advice or suggestions to students apart from expressions of moral support when the latter took to the streets and appealed to the authorities for democracy."

"Whereas the basic dividing line in the 1980s was 'reform or no reform', in the 1990s it changed to 'Which reform do you prefer?'", he said.

Patrick Boehler

Cedric Sam

Silvio Carrillo

Vicky Feng

Robin Fall

Jeff Chen

Pearl Law

Kaliz Lee

Joe Lo

Adolfo Arranz

Suzanne Sataline

Kristine Servando

Sofia Mitra-Thakur

The Gate of Heavenly Peace, documentary by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton

Laurence Chu

Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China

SCMP content resources

Associated Press

Agence France-Presse

Reuters

European Pressphoto Agency

Yuen-ying Chan

Karen Chang

Susan Jakes