In 2019, Hui was selected to present the next Audemars Piguet Art Commission, in the fifth edition of the competition under the auspices of Audemars Piguet Contemporary, which fosters and supports a creative community of contemporary artists working today.

Speaking to the South China Morning Post’s Morning Studio team from her studio in the Hong Kong Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre – which she has considered to be her second home for the past 10 years – Hui recalls how her inspiration for the installation came from a trip to Le Brassus, Switzerland, to visit the headquarters of Audemars Piguet.

During the trip, Hui was invited to have dinner at a family-run restaurant in the village nestled among snow-covered mountains, and took a walk after the meal.

Hong Kong-based artist Phoebe Hui is presenting her works in the first Audemars Piguet Art Commission to be shown in Asia. Photo: Audemars Piguet

Hong Kong-based artist Phoebe Hui is presenting her works in the first Audemars Piguet Art Commission to be shown in Asia. Photo: Audemars Piguet

“For an artist who was born and lives in Hong Kong, the experience of walking on snow at night was unique and awe-inspiring,” says Hui, who graduated from City University of Hong Kong’s School of Creative Media before earning a master’s degree from Central Saint Martins in London and later completing the design media art master’s programme at the University of California, Los Angeles.

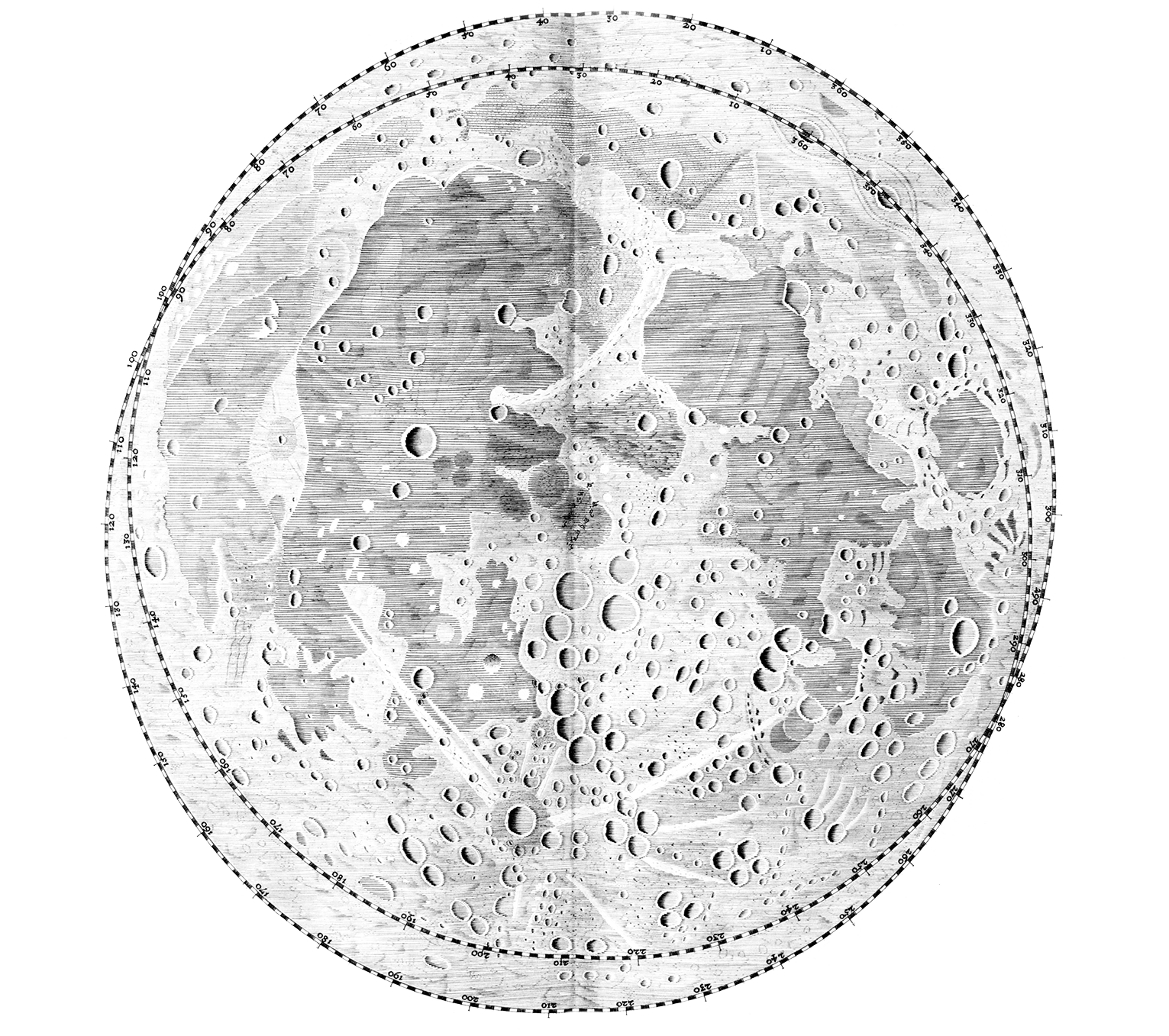

“I felt so close to the Earth because of the soundscape of the tranquil forest – it was completely different from my daily experience,” she adds. “The shimmering light from the moon illuminated the snowy mountains.”

Since then, her imagination has often returned to the moon.

“I feel that our complex emotional ties with it are yet to be fully explored and reflected on,” Hui says. “I have aspired to transform the space that we will be occupying at Tai Kwun into an urban sanctuary for audiences to explore, reflect, build or rebuild their relationships with our universe.”

The guest curator for the Art Commission, chosen with the support of Audemars Piguet Contemporary, is Ying Kwok, recently appointed as senior curator (digital and heritage) at Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, and who notably curated the Hong Kong presentation at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017. Kwok says that she thinks of Hui as “a visual poet” who researches and dissects information in order to present an interpretation – or, at times, a reinterpretation – of information.

Ying Kwok, senior curator (digital and heritage) at Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, is the guest curator for the Art Commission. Photo: Audemars Piguet

Ying Kwok, senior curator (digital and heritage) at Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts, is the guest curator for the Art Commission. Photo: Audemars Piguet

Indeed, research is fundamental in Hui’s creative process. For the exhibition, she says inspiration was drawn from a broad range of areas that include “literary theory, quantitative research methodology, system aesthetic, media archaeology and the philosophy of science”.

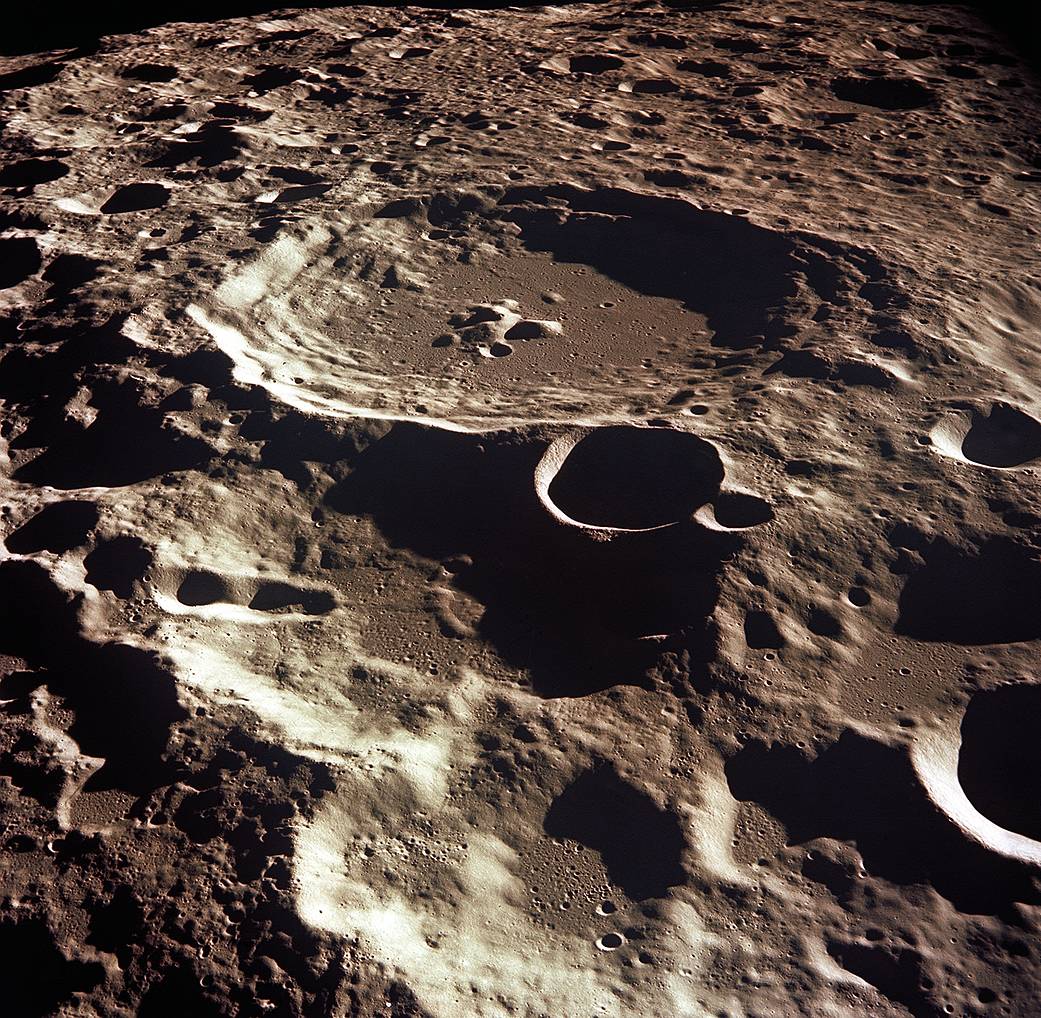

Earth is seen rising over the moon's horizon in this shot taken from the Apollo 11 space mission, which first landed humans on the moon. Photo: Nasa

Earth is seen rising over the moon's horizon in this shot taken from the Apollo 11 space mission, which first landed humans on the moon. Photo: Nasa

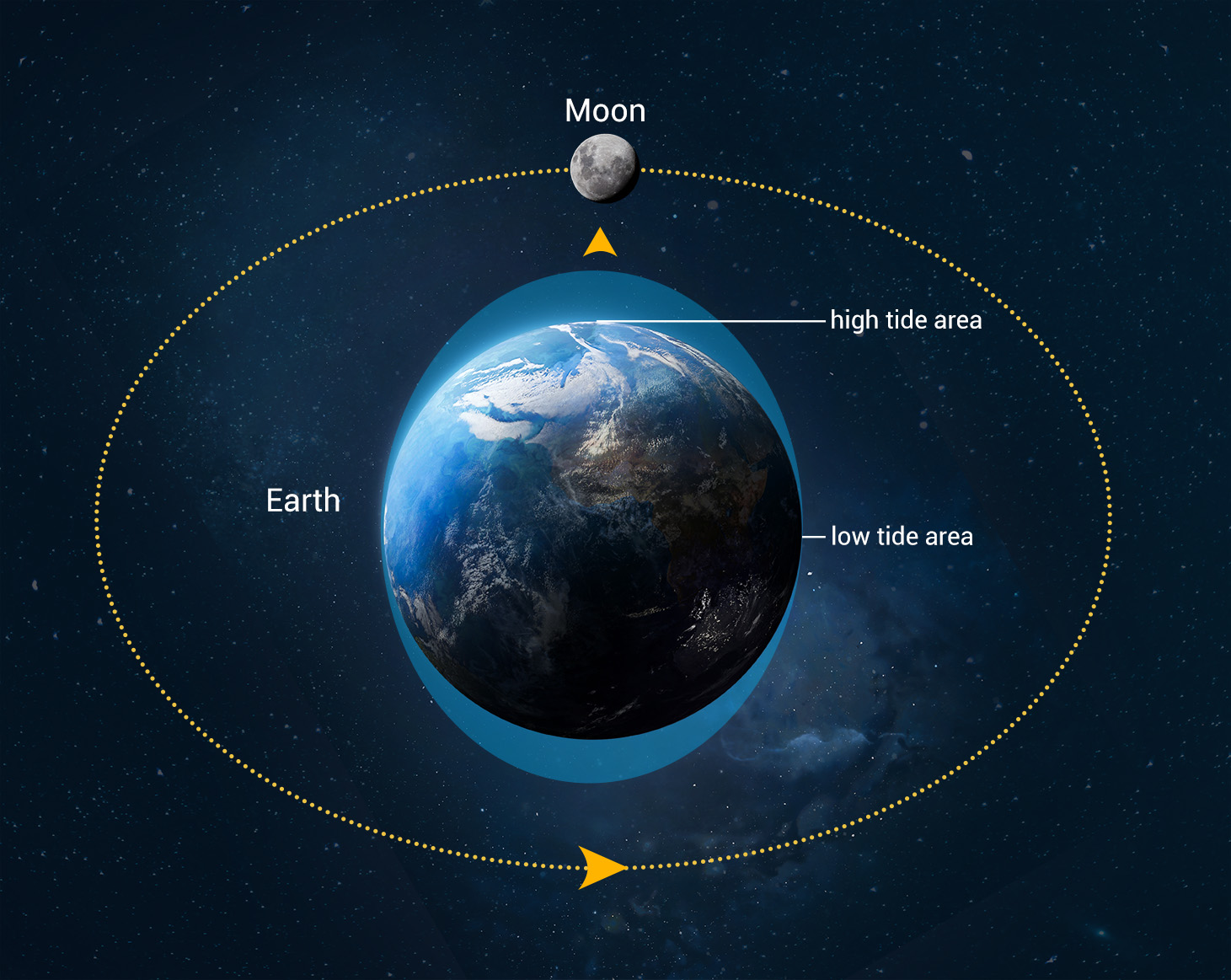

The moon exerts a gravitational pull on the Earth, causing its oceans to form a tidal bulge.

The moon exerts a gravitational pull on the Earth, causing its oceans to form a tidal bulge.