Architecture post-coronavirus

Global efforts to contain Covid-19 have led to mass lockdowns, turning densely populated cities into ghost towns. Our daily routines and how we interact with our environments have changed — possibly forever.

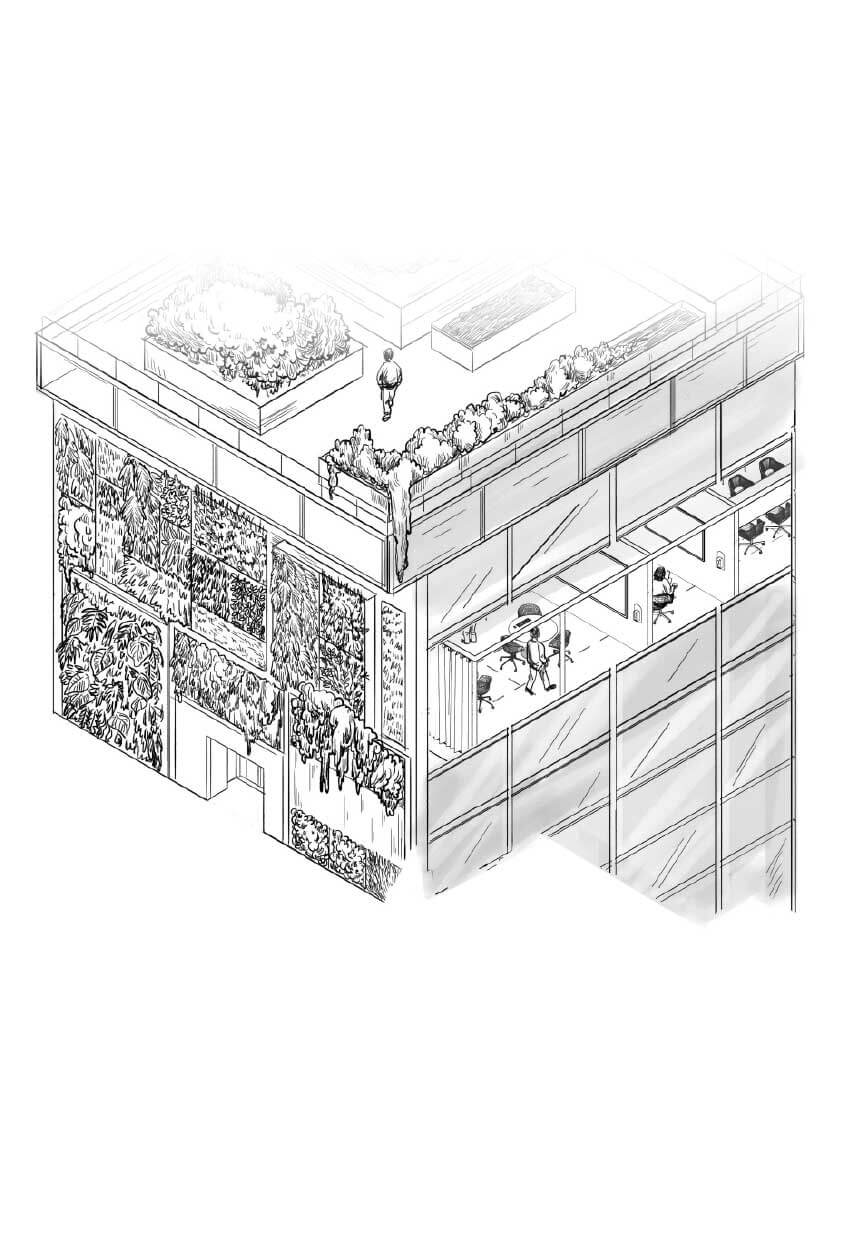

Architects and urban designers are finding ways to adapt the spaces we live and work in amid the coronavirus pandemic.

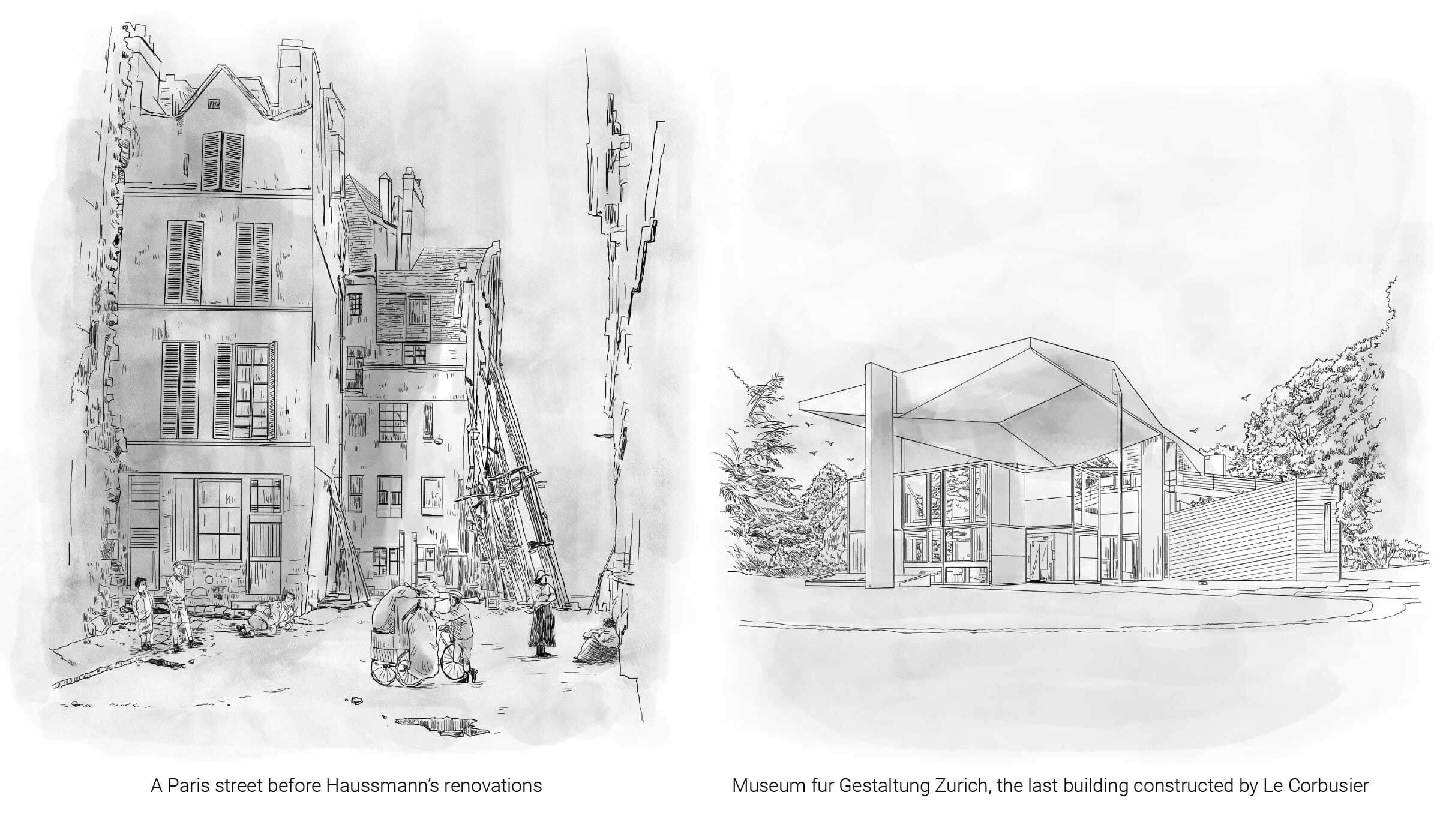

Through history, they have joined the fight against infectious diseases. In the 1800s, Georges-Eugene Haussmann, commonly known as Baron Haussmann, led a vast public works programme to renovate Paris. This included demolishing overcrowded medieval neighbourhoods that were dark, damp, and disease-ridden.

Across the Channel, London went through a similar transformation after devastating cholera outbreaks.

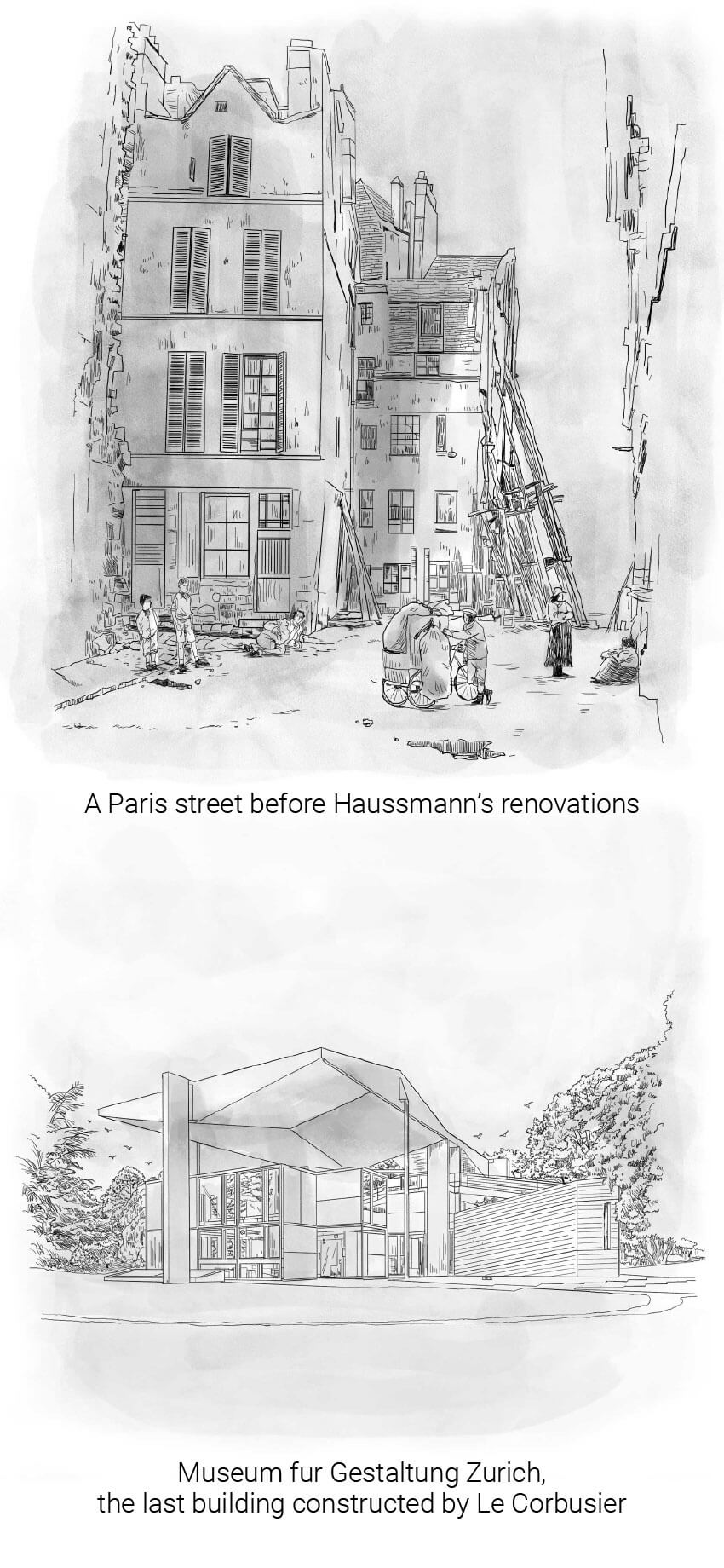

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, continued to update the design of public spaces as architecture entered its modernist era from the 1930s to the 1970s. The Swiss architect urged people to rid their homes of needless clutter, strip out carpets, ditch heavy furniture, and keep floors and walls bare to promote “inner cleanness”. Construction with glass, steel and reinforced concrete became more common.

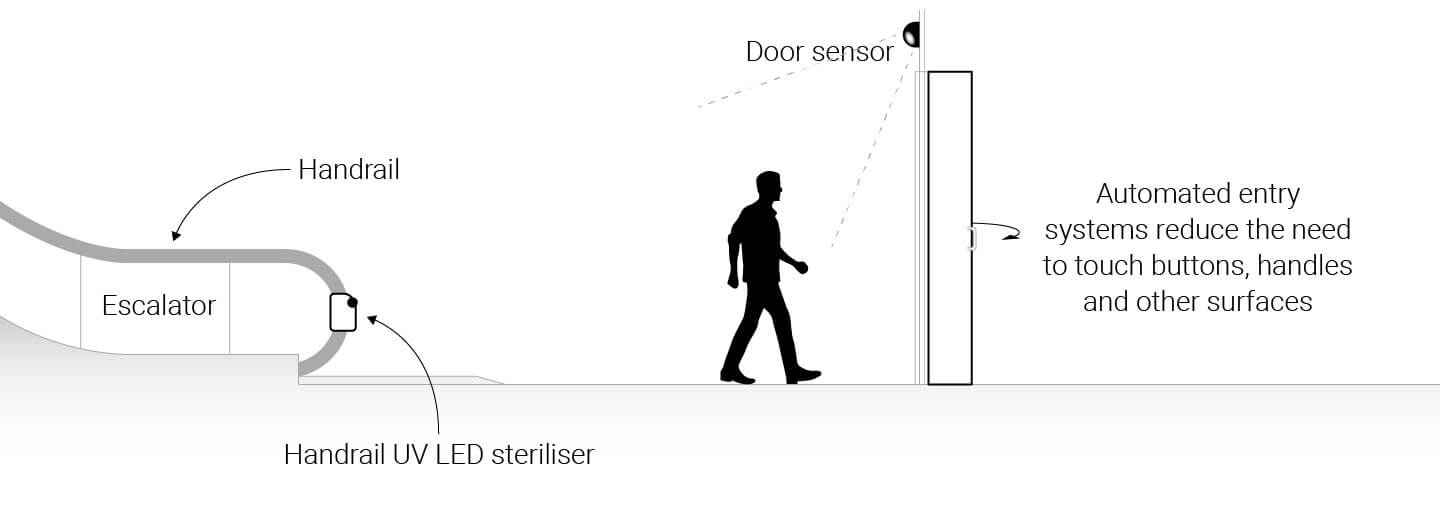

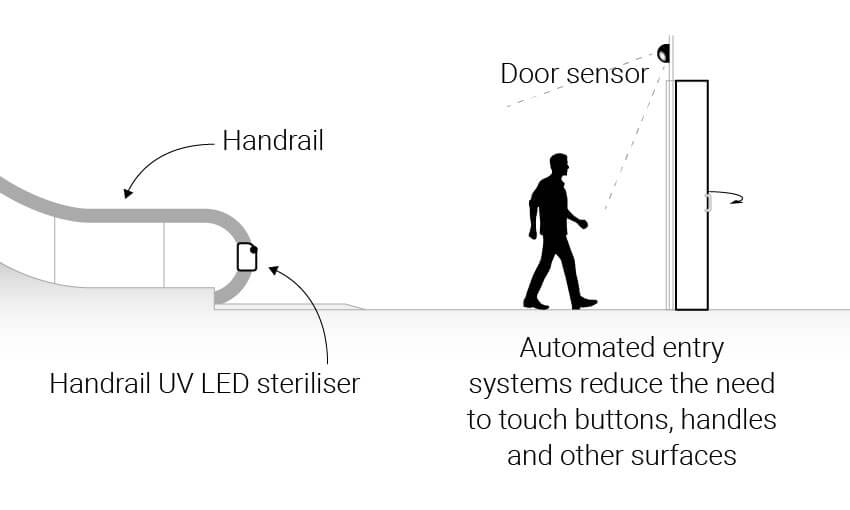

About 80 per cent of infectious diseases are transmitted through contact with contaminated surfaces, according to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

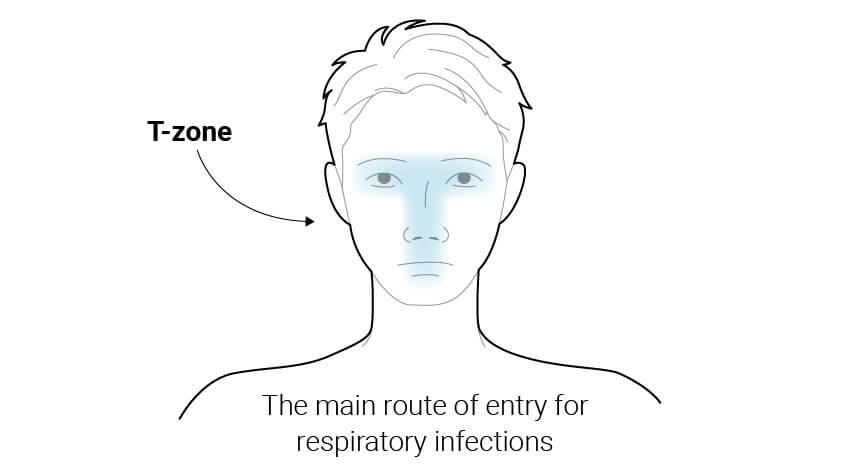

The “T-zone” of the face — the eyes, nose and mouth — is the main portal of entry for infections, such as those caused by the coronavirus. Various studies have shown that people touch their face about 23 times an hour, half of them in this T-zone. While behaviour can be hard to change, technology can reduce the need to touch some surfaces. Smartphone apps can summon elevators, facial recognition technology can open doors and antimicrobial materials can help reduce infection risk.

DON’T TOUCH YOUR FACE

At home

Coronavirus lockdowns, curfews and other restrictions have forced many people to work from home for prolonged periods. This created challenges for some who share their home with other people, especially if space and privacy is at a premium.

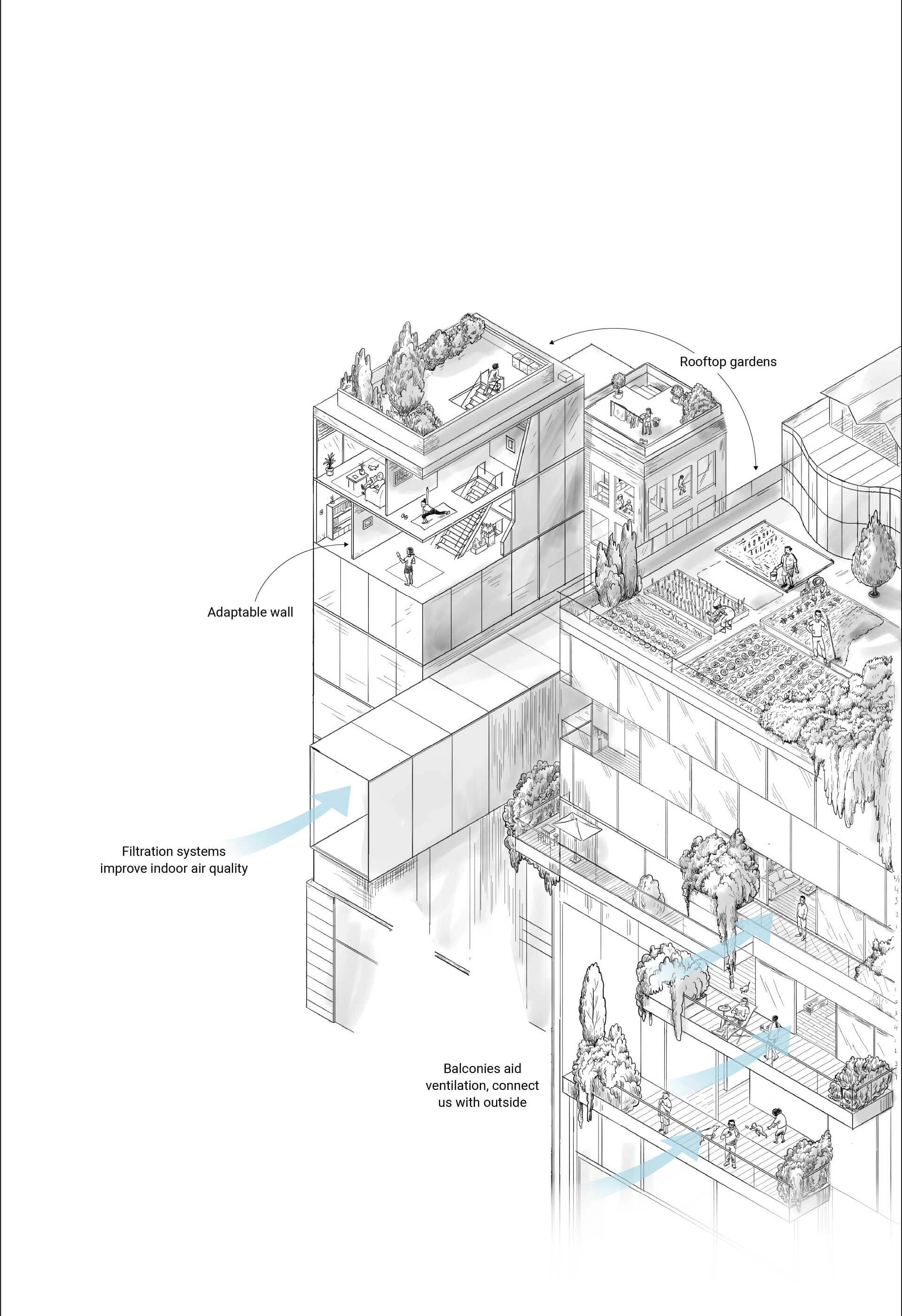

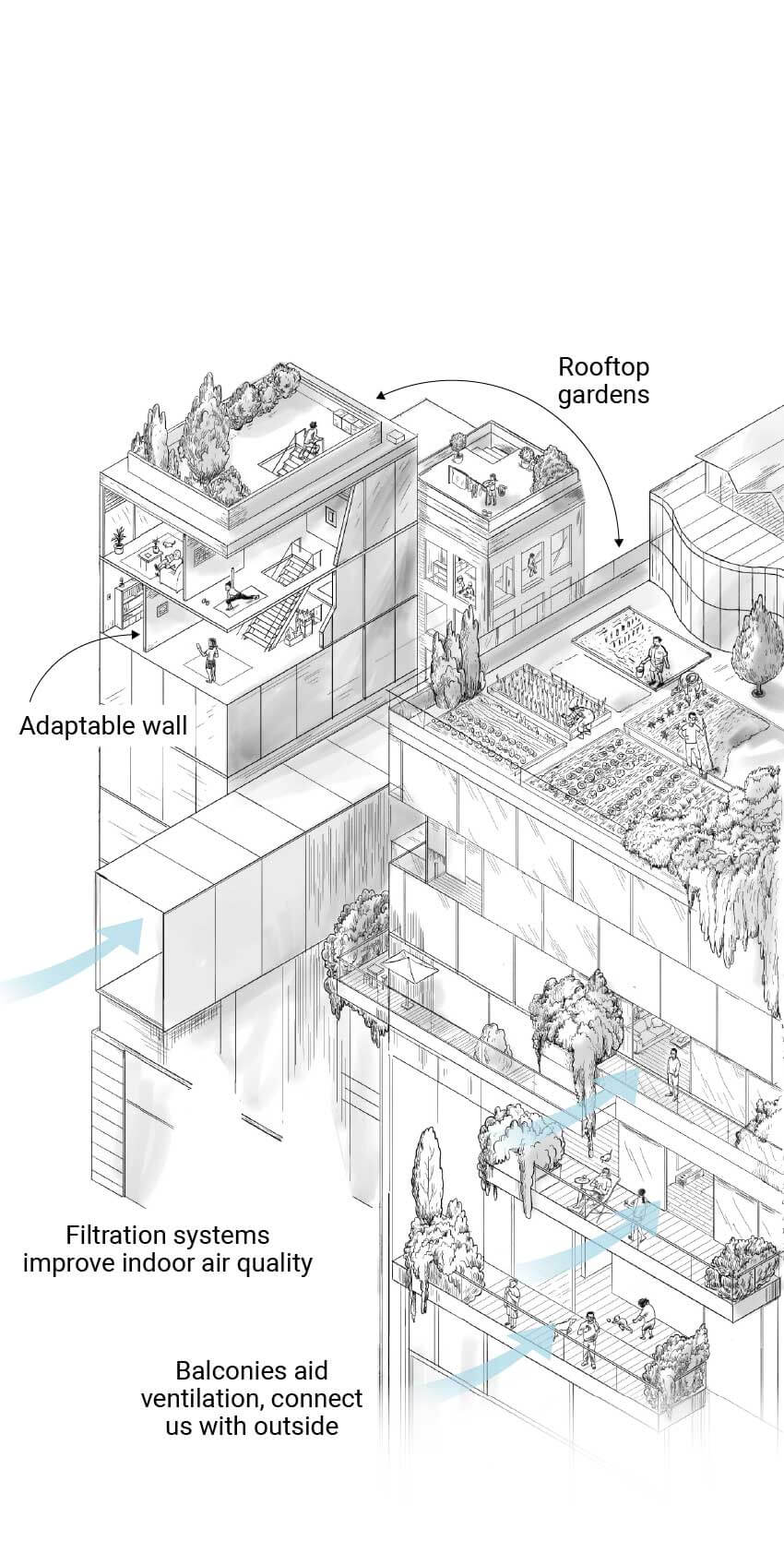

With a bit of imagination — and space — homes can have flexible living areas. Rooms that feature moving walls and other adaptable interiors can serve multiple functions, like for work space or casual living. However, this isn’t always feasible in high-density cities like Hong Kong, where flats are small: the average size is about 484 square feet (45 square metres).

FLEXIBLE LIVING SPACES

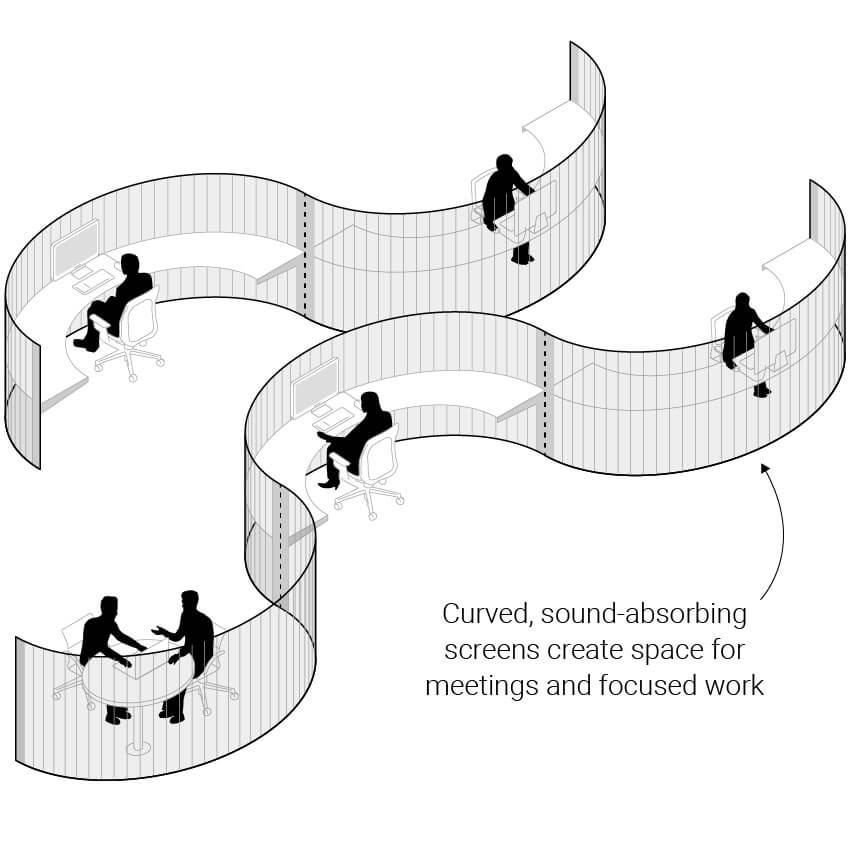

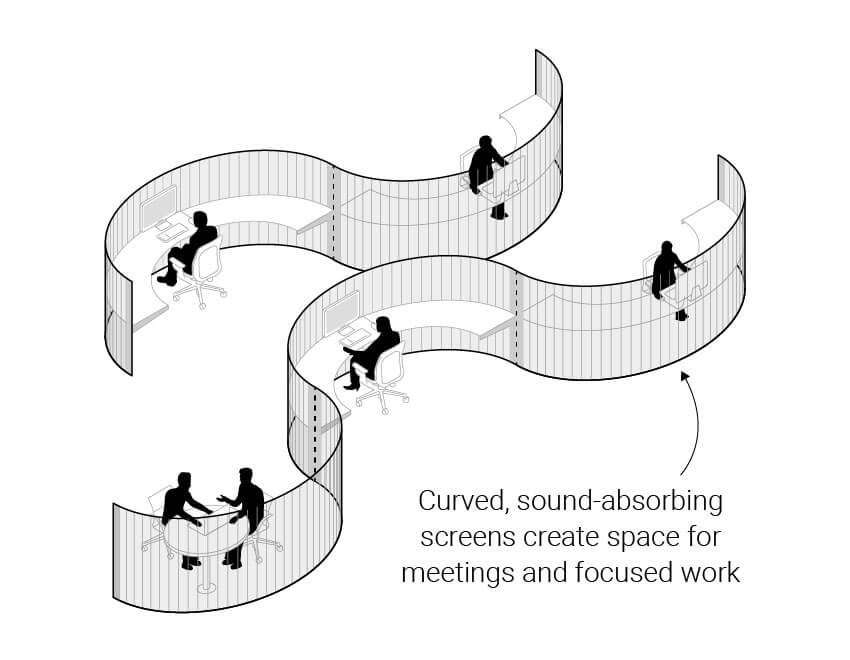

At work

The coronavirus pandemic is also changing the way we work. Offices with flexible-seating arrangements have become increasingly common as more people work from home, allowing companies to consider leasing less floor space to save money.

Technology

Technology can help protect us from viruses. Automatic doors have been around for years, but they have been especially important in the pandemic, like other touchless technologies. So too, have air cleaners and HVAC filters (heating, ventilation, air conditioning). Air purifiers can help reduce airborne contaminants, including viruses, in confined spaces, but not enough to totally protect people from Covid-19. Scientists have been studying ways to improve the safety of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) technology that can disinfect rooms.

COMMONLY TOUCHED SURFACES

FUTURE OF AI

Hover/tap for information

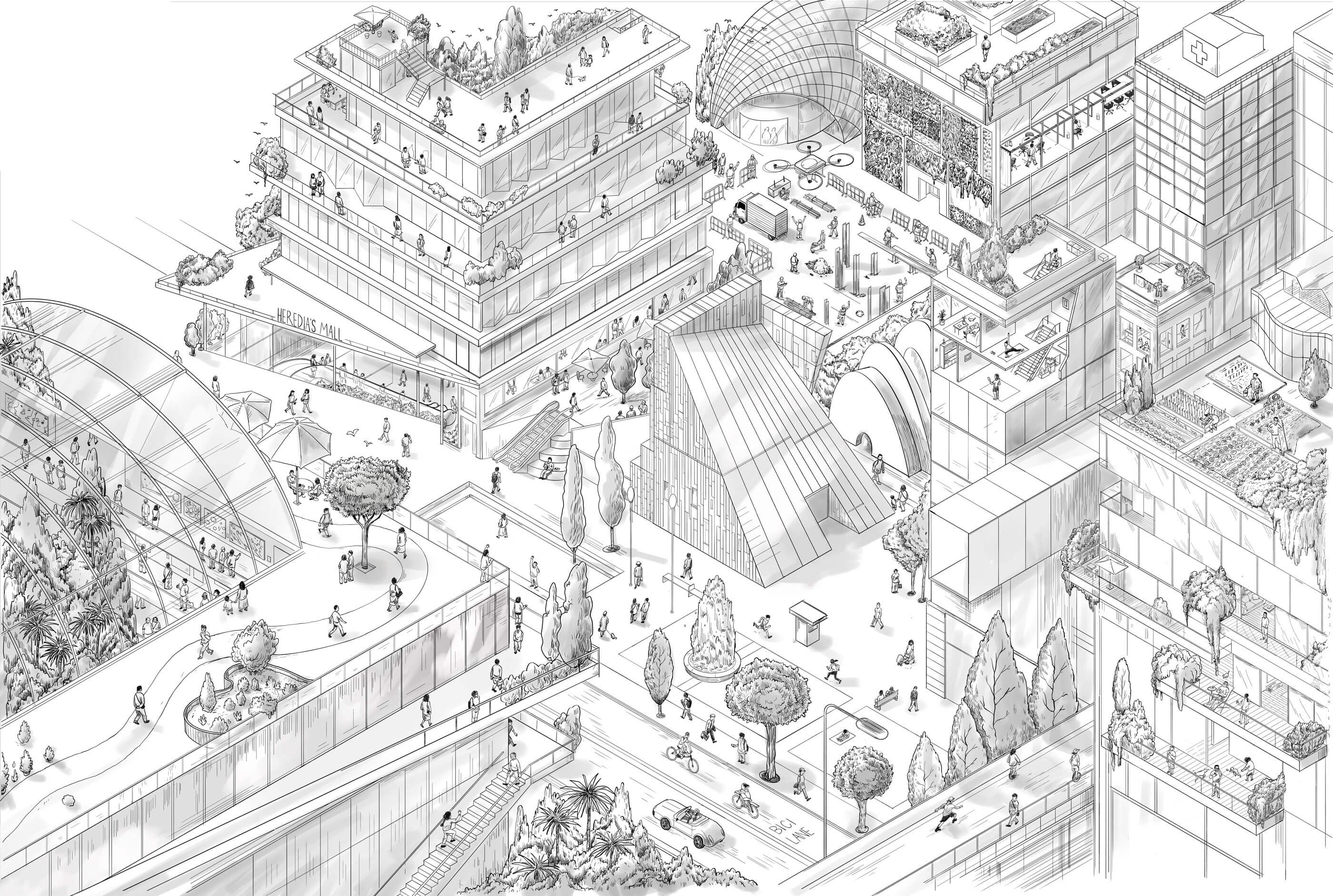

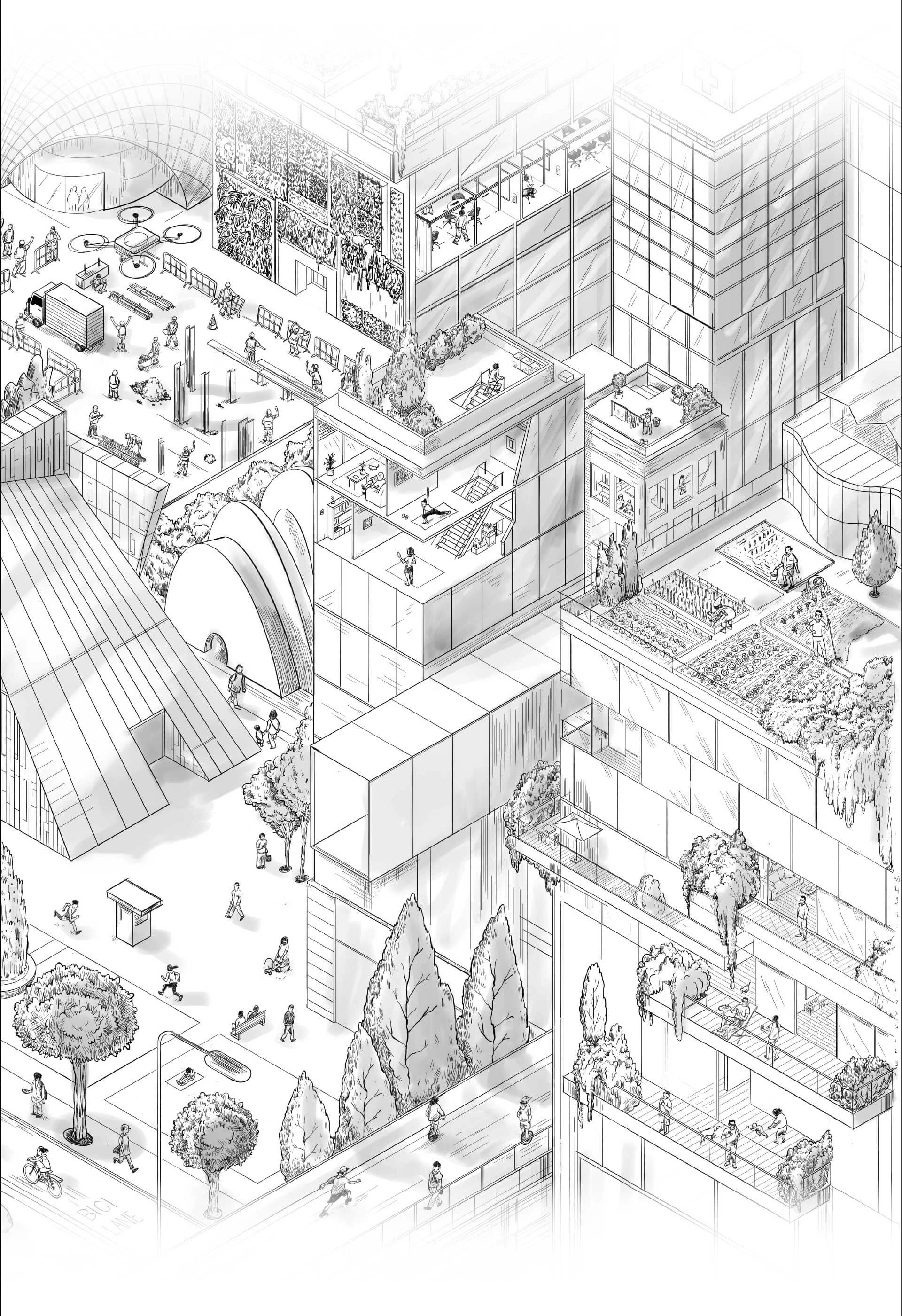

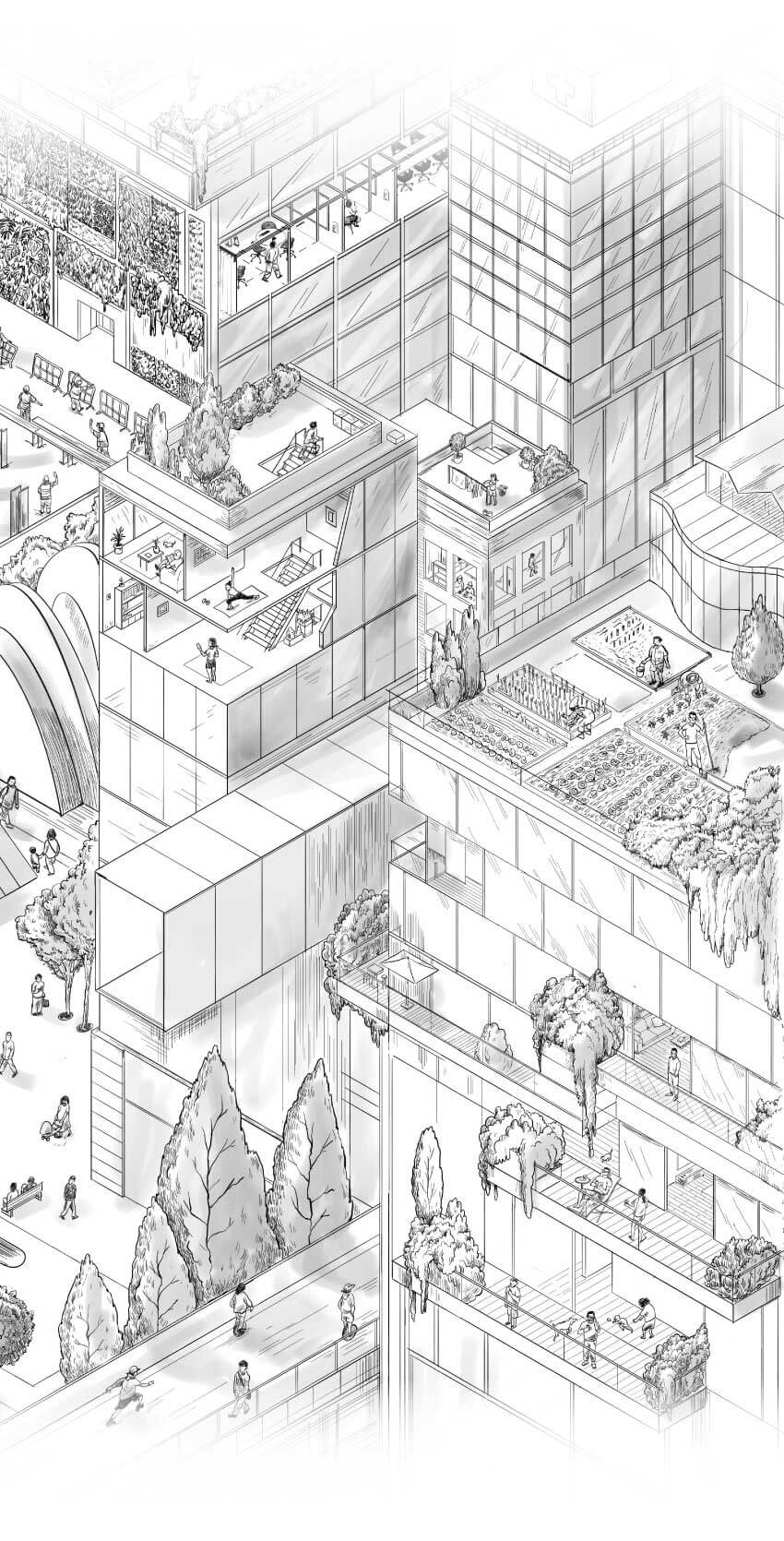

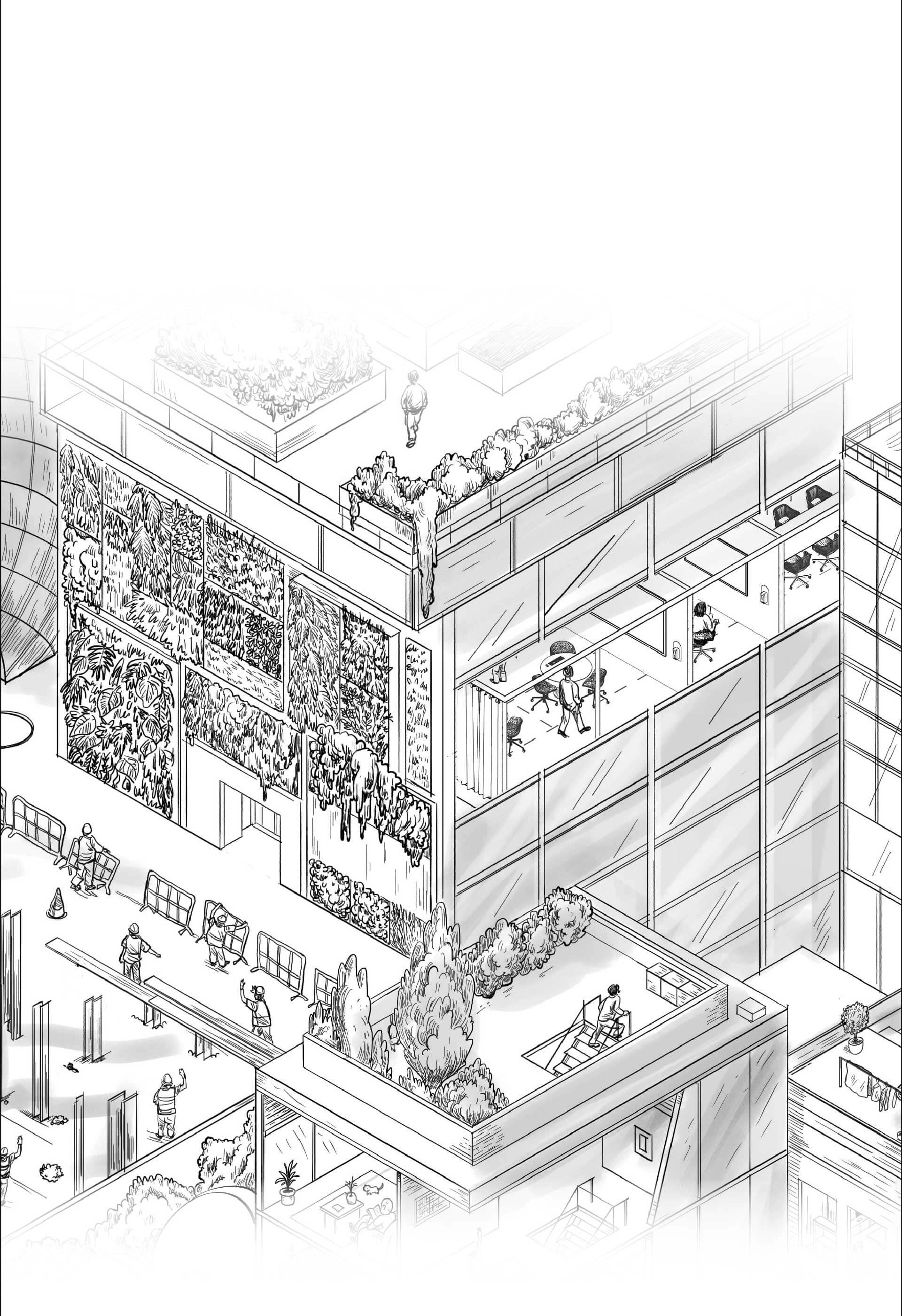

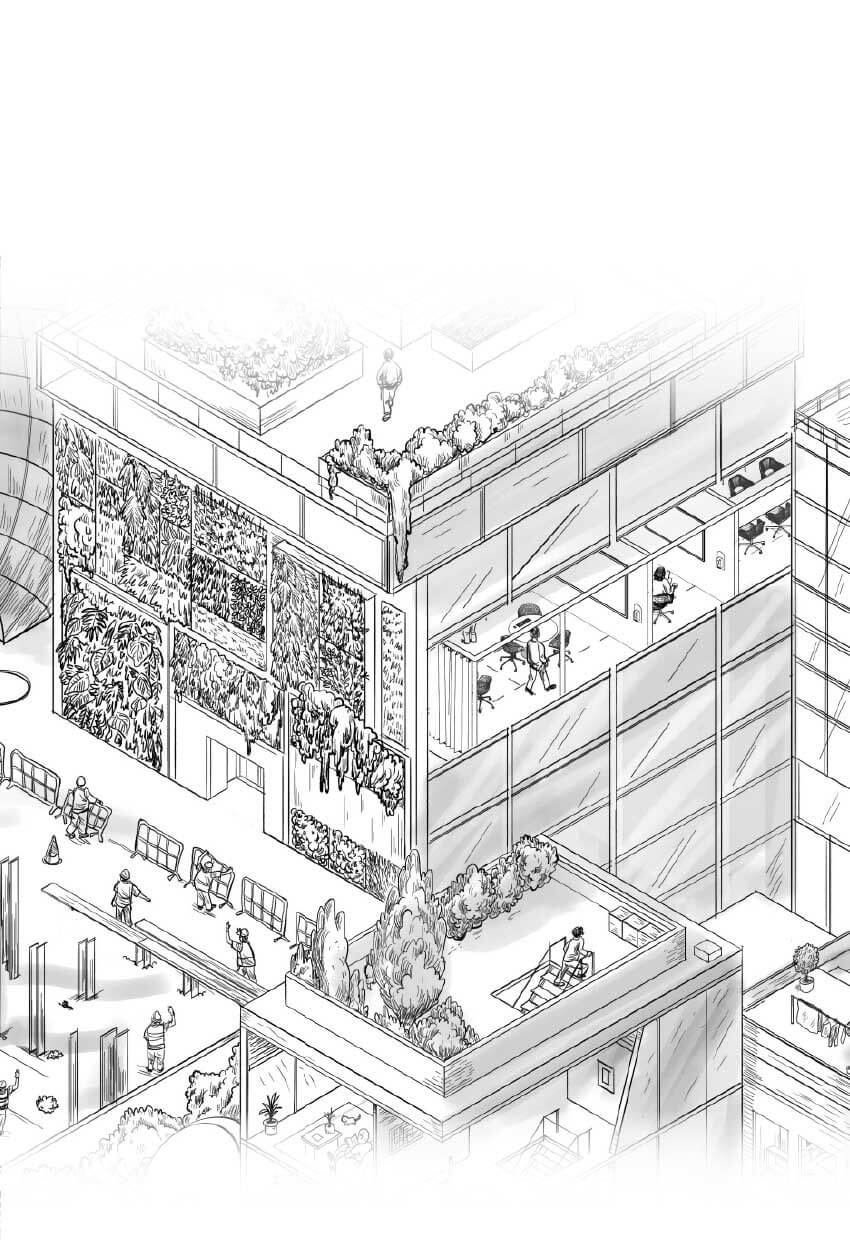

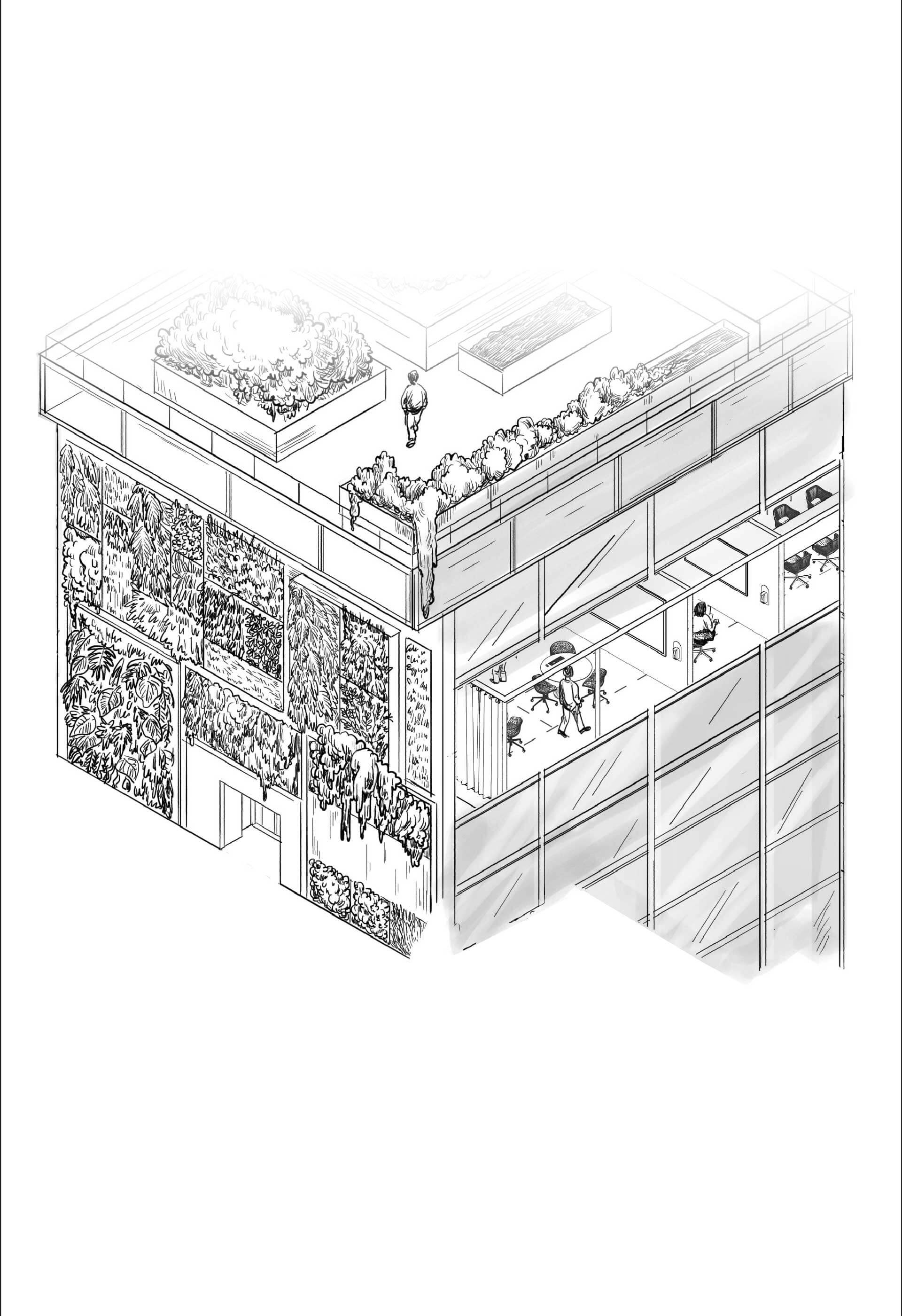

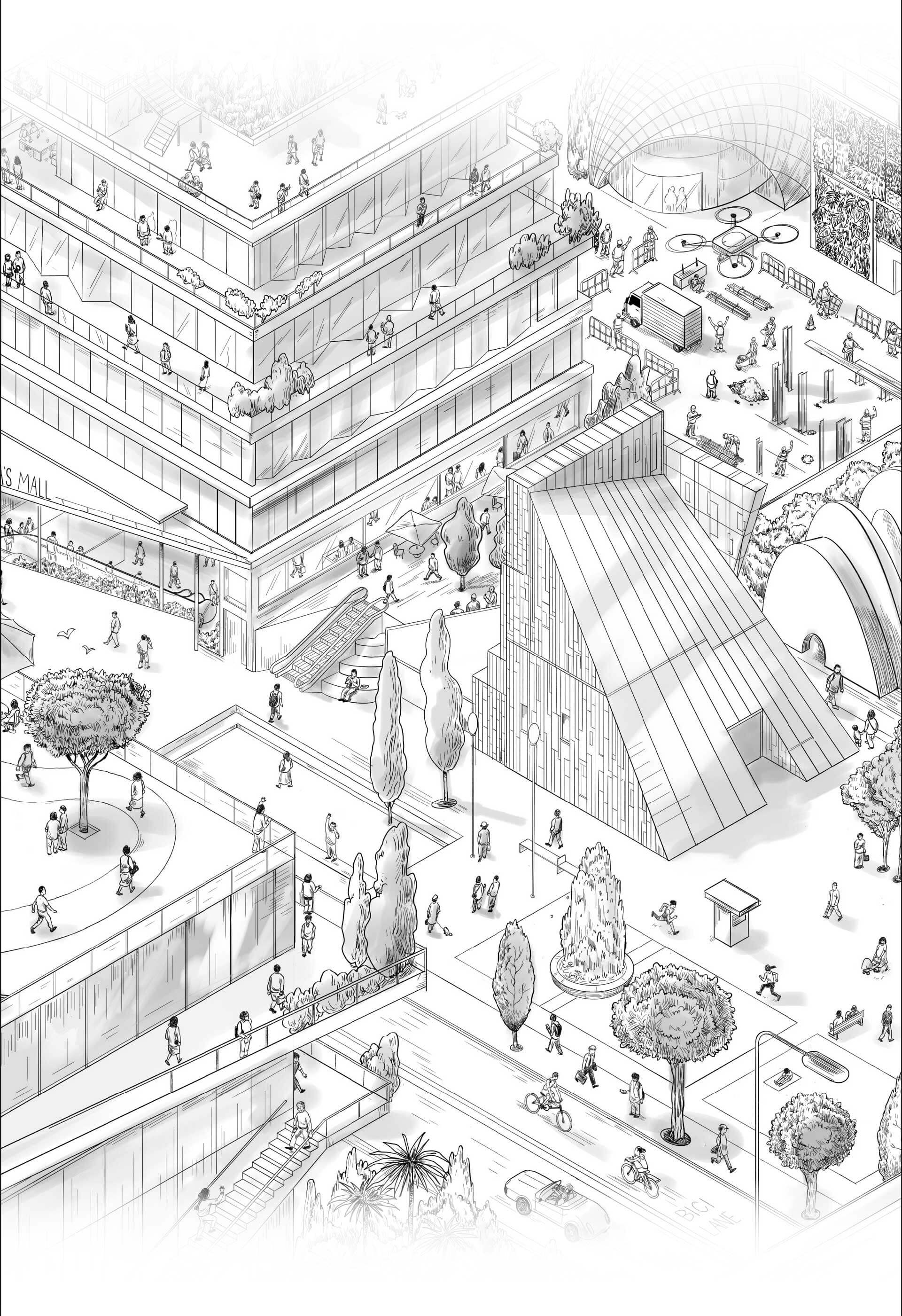

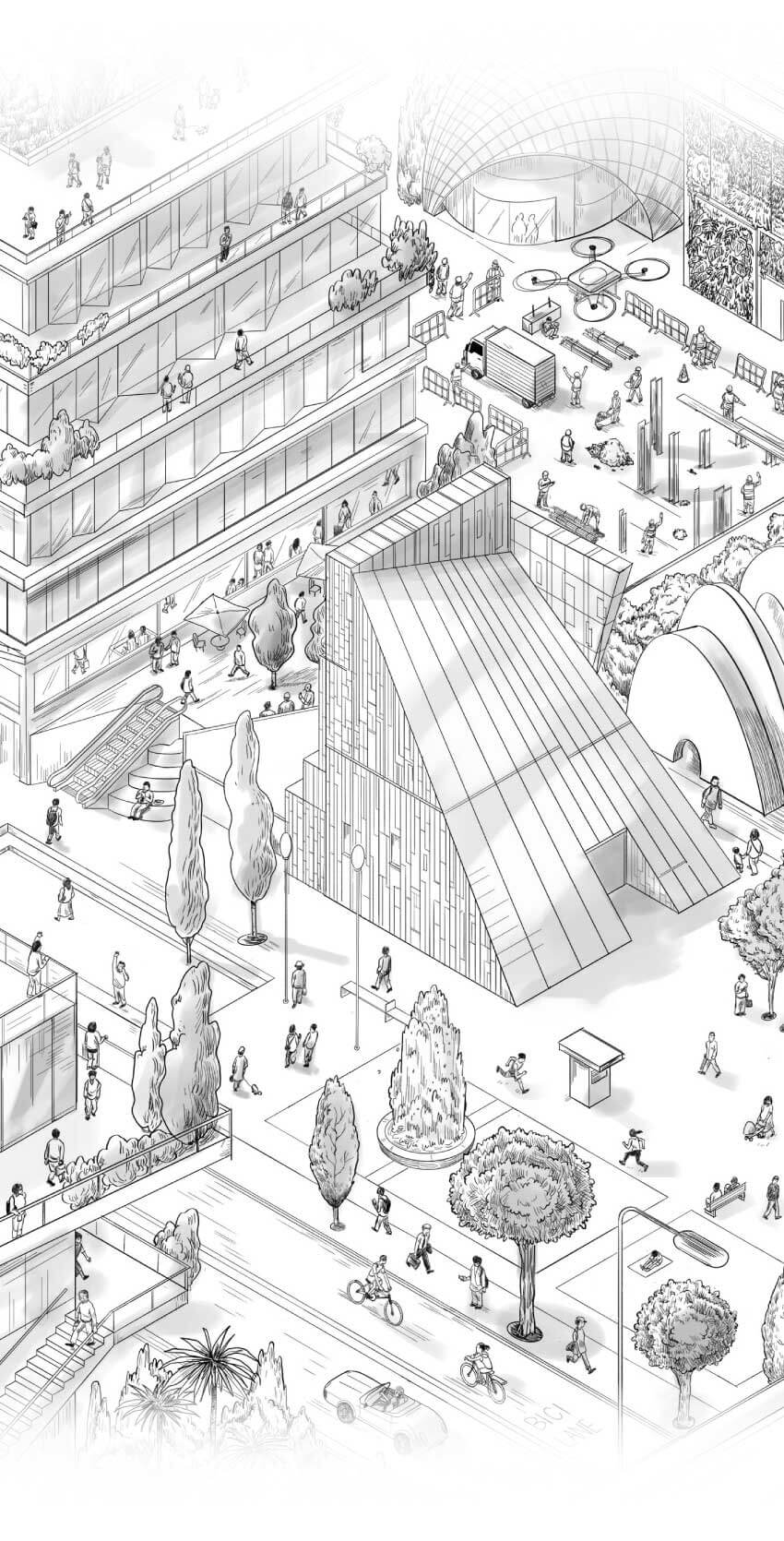

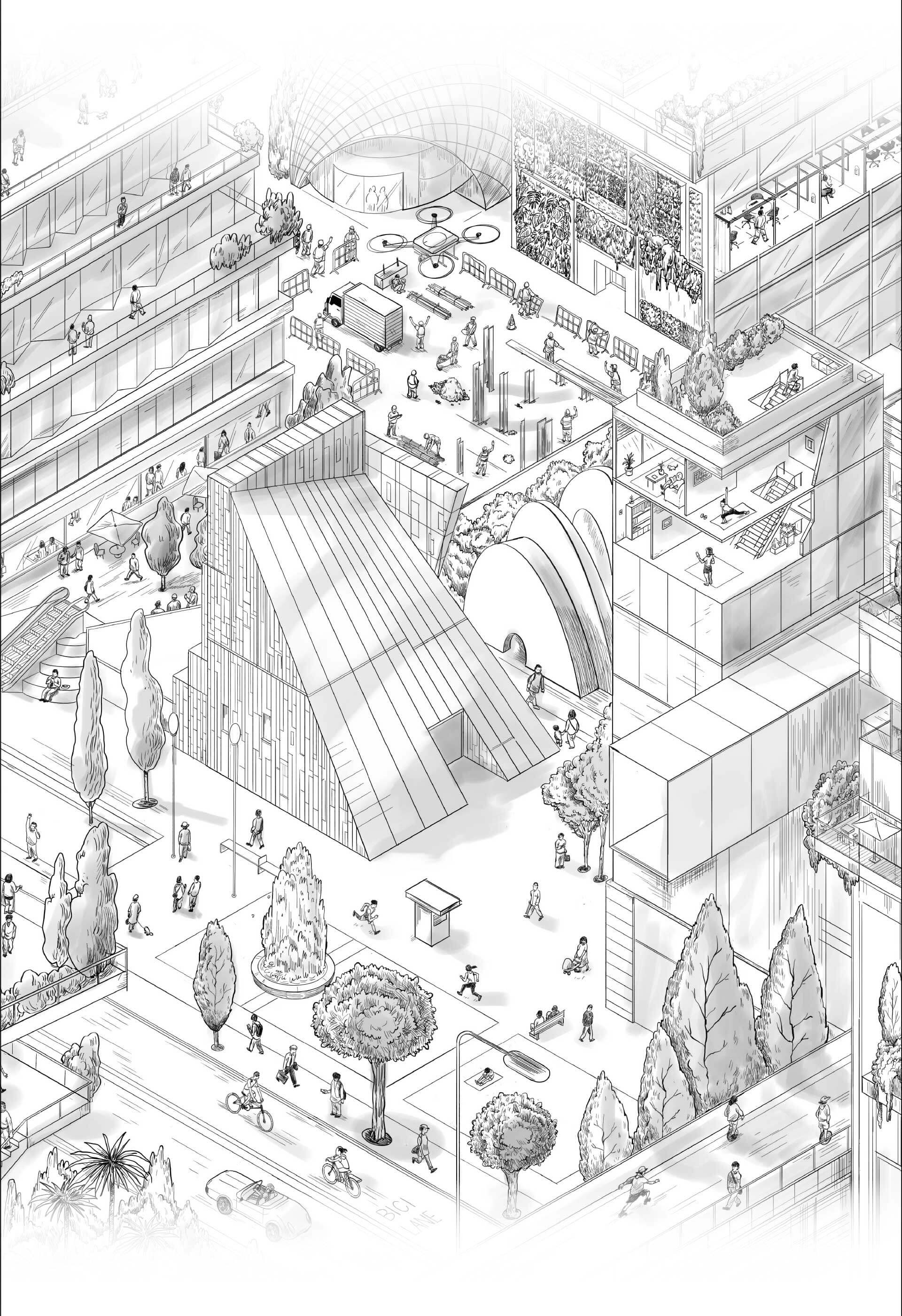

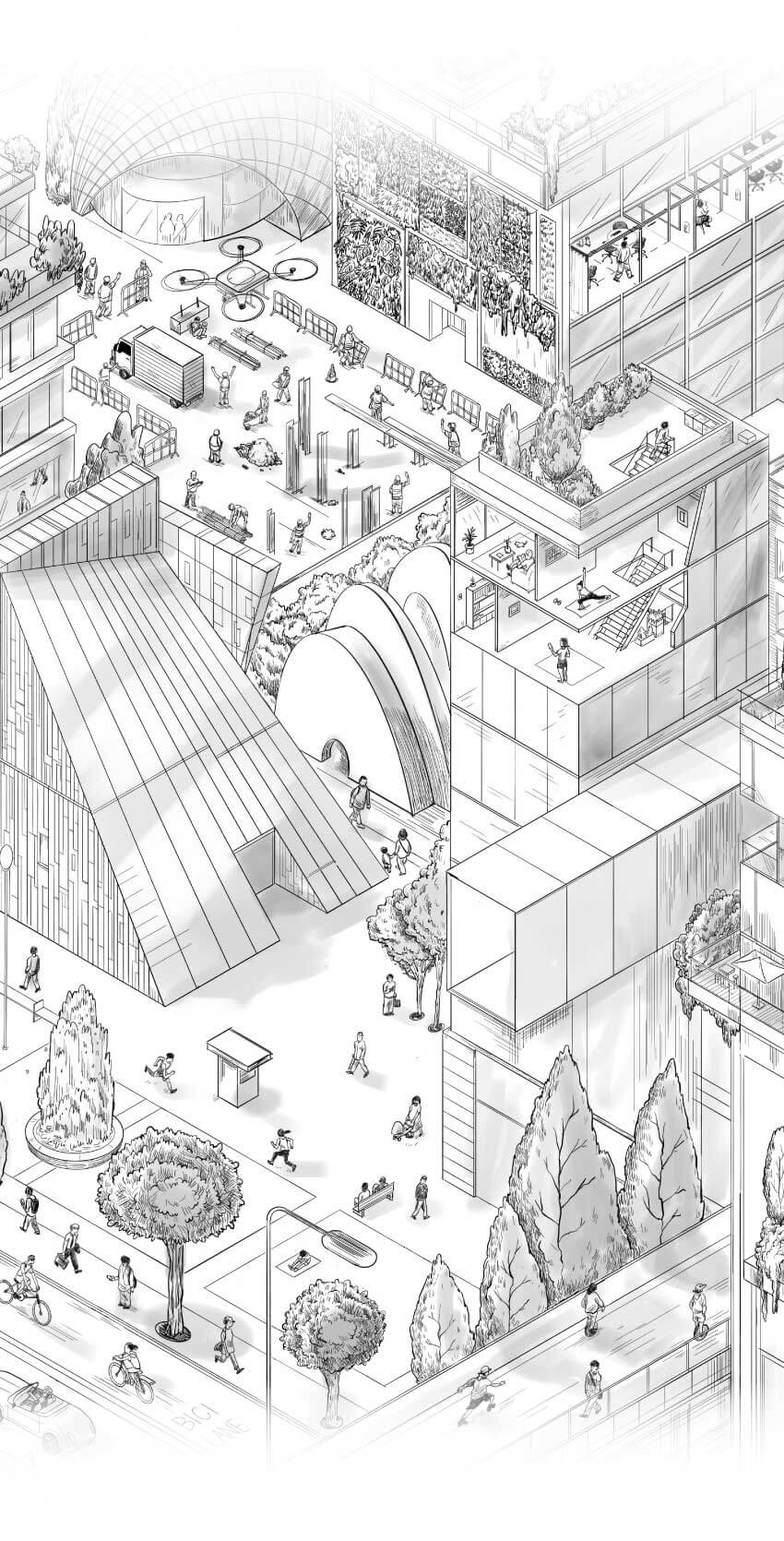

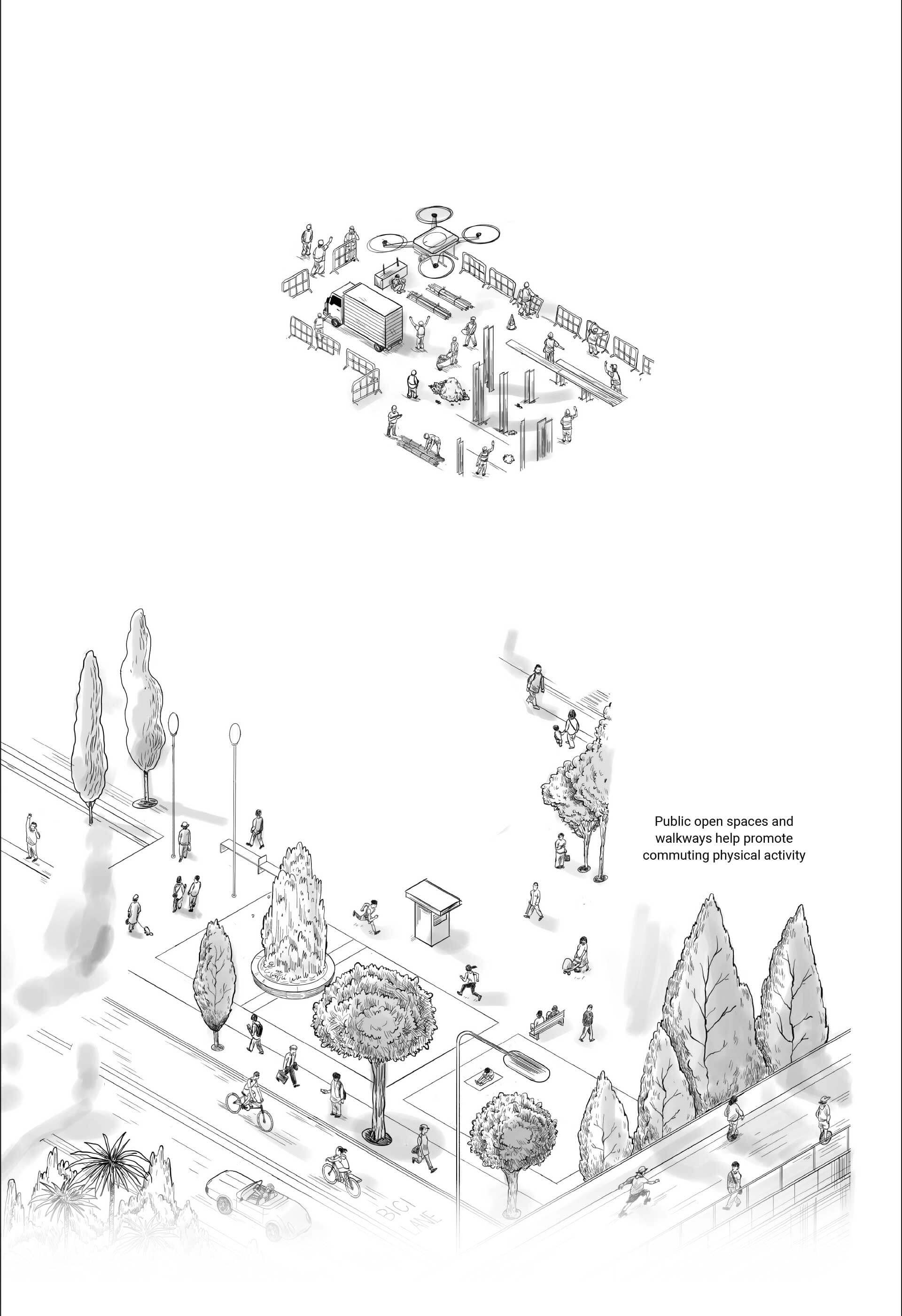

Mixed-use environments

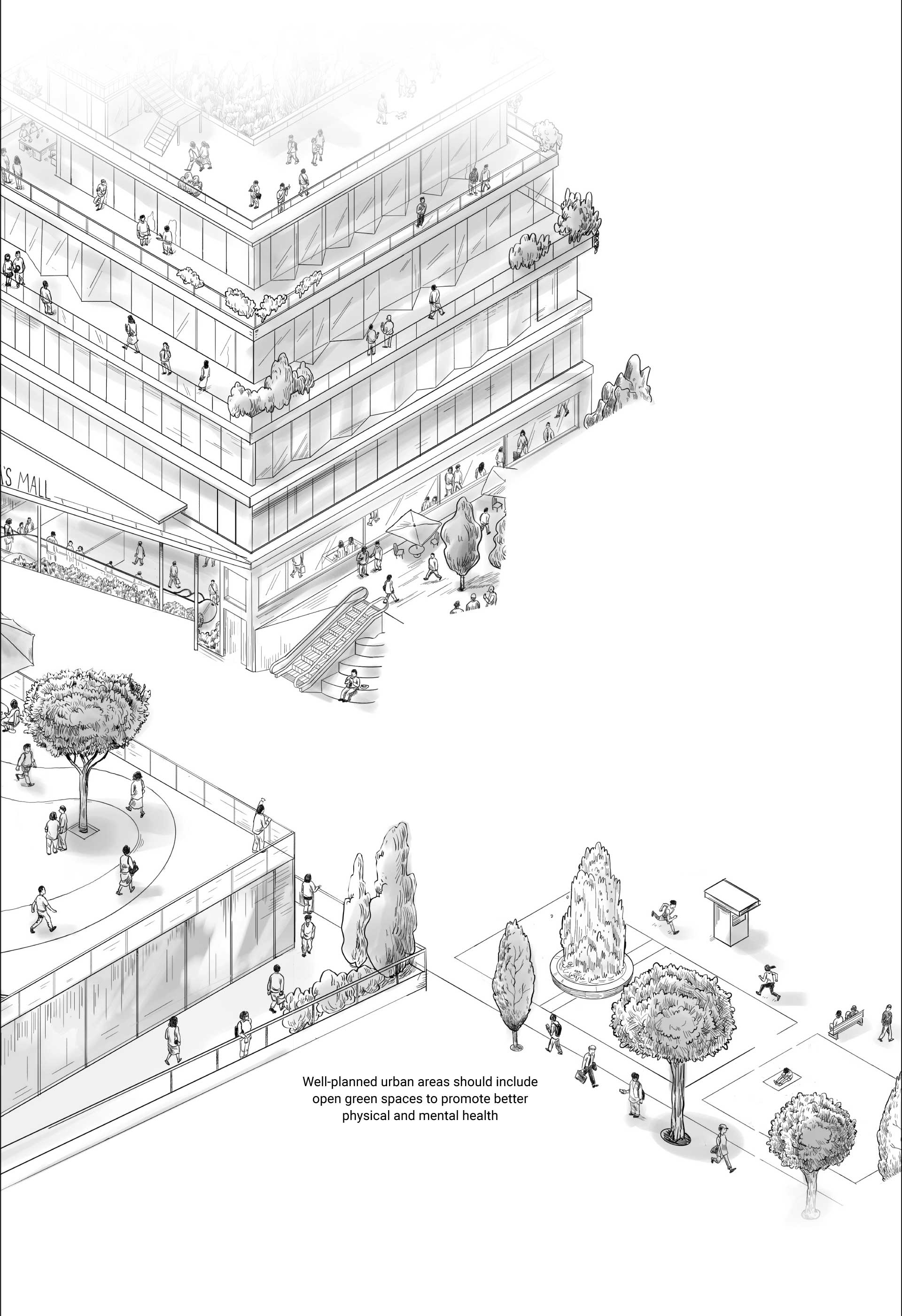

A mixed-use neighbourhood has residential and commercial space in a shared environment. What will these developments be like after this pandemic? Architects and urban planners are exploring ways to make them safe, convenient, and vibrant.

Coronavirus surfaces: Some materials such as copper, brass and bronze have natural antimicrobial properties. Covid-19 survives for about four hours on copper, compared to 24 hours on cardboard, 72 hours on plastic and stainless steel, and about 96 hours on glass.

HOW MANY DAYS CAN THE CORONAVIRUS SURVIVE ON MATERIALS?

Hospitals

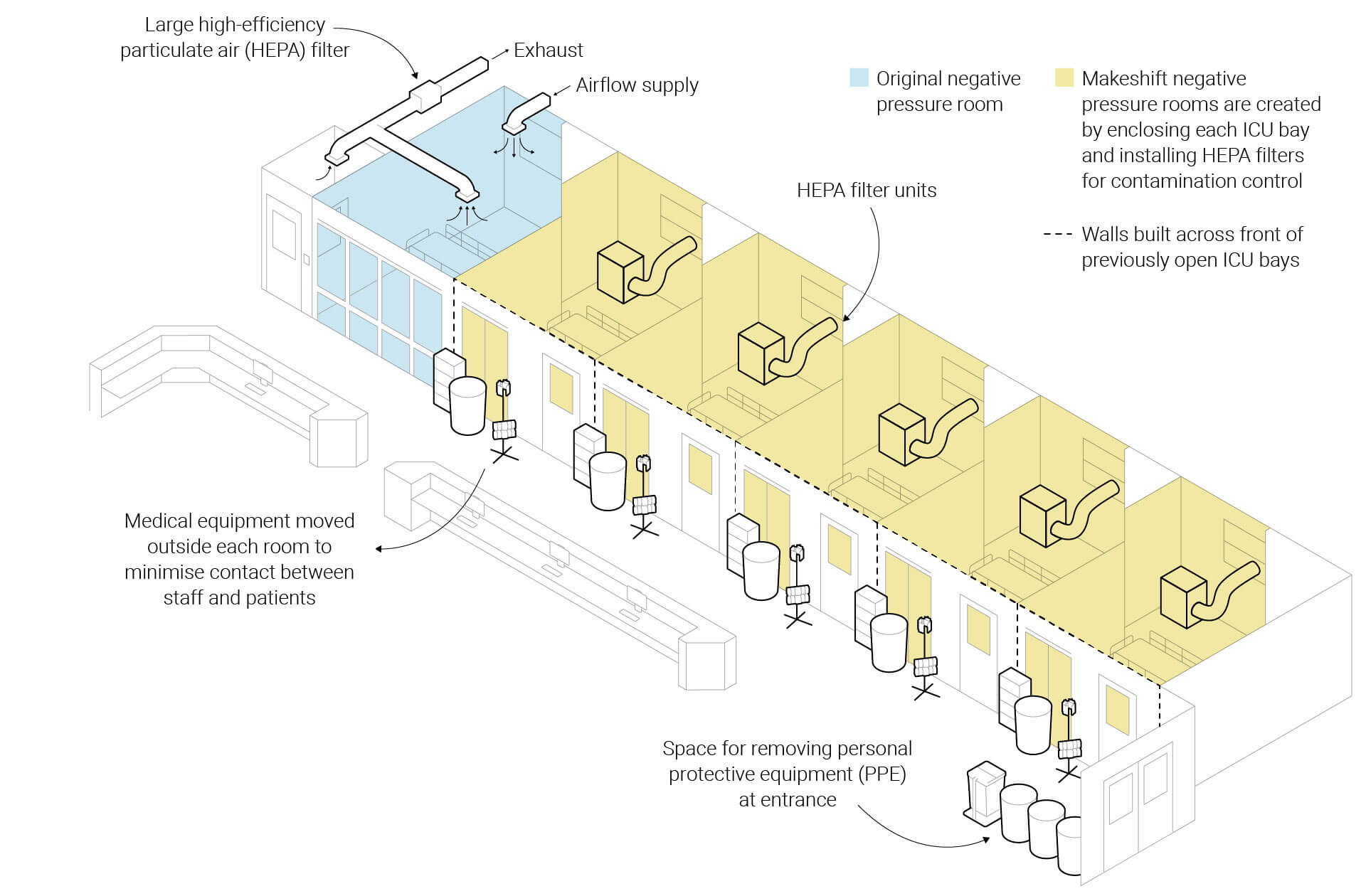

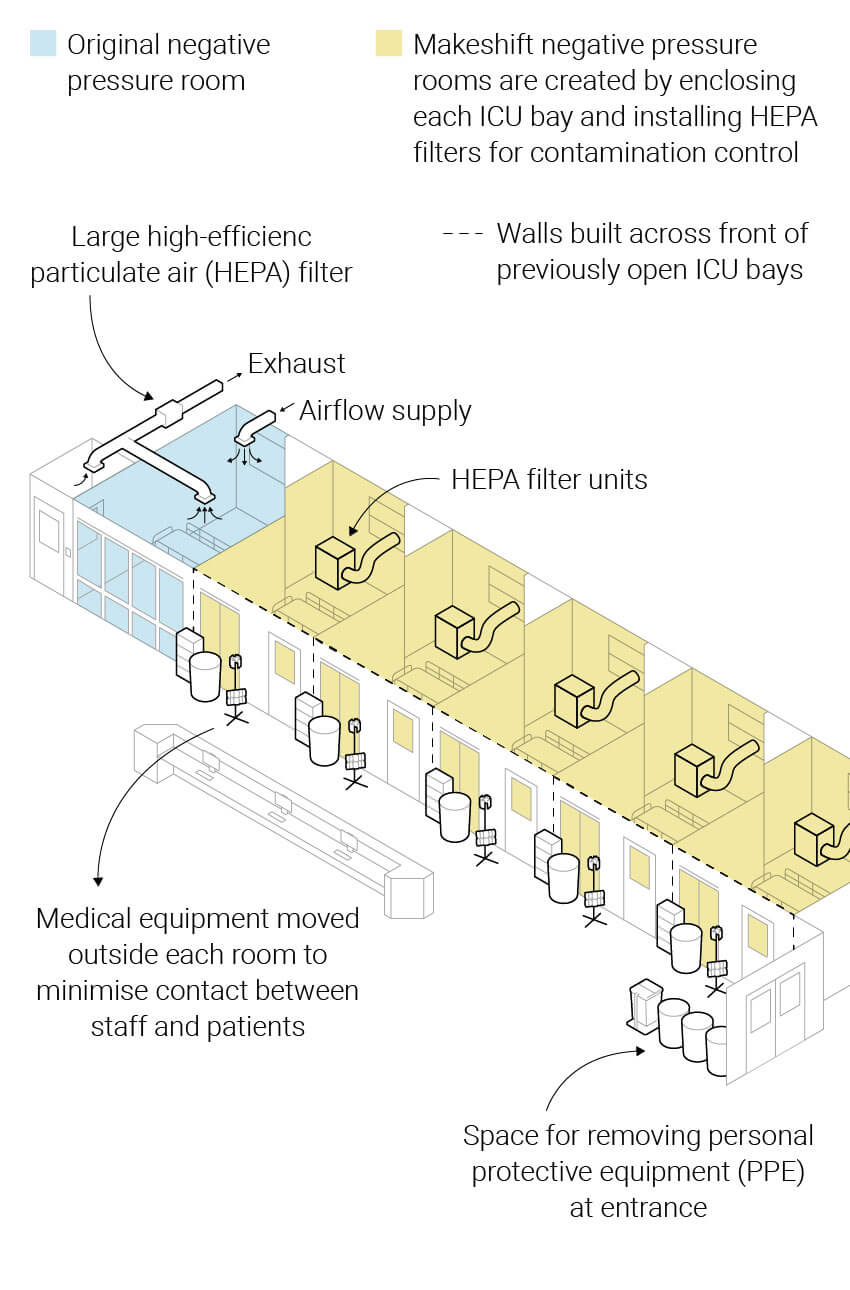

Hospitals are at the front line of the Covid-19 war. But many have struggled because of shortages of protective gear, ventilators and beds in special isolated rooms. Hospital operators are consulting with experts to help redesign existing medical facilities and boost the capacity of intensive care units.

ADAPTING THE ICU WING FOR COVID-19

The air pressure inside negative pressure rooms is lower than the air pressure outside. This means that when the door is opened, contaminated air inside should not escape.

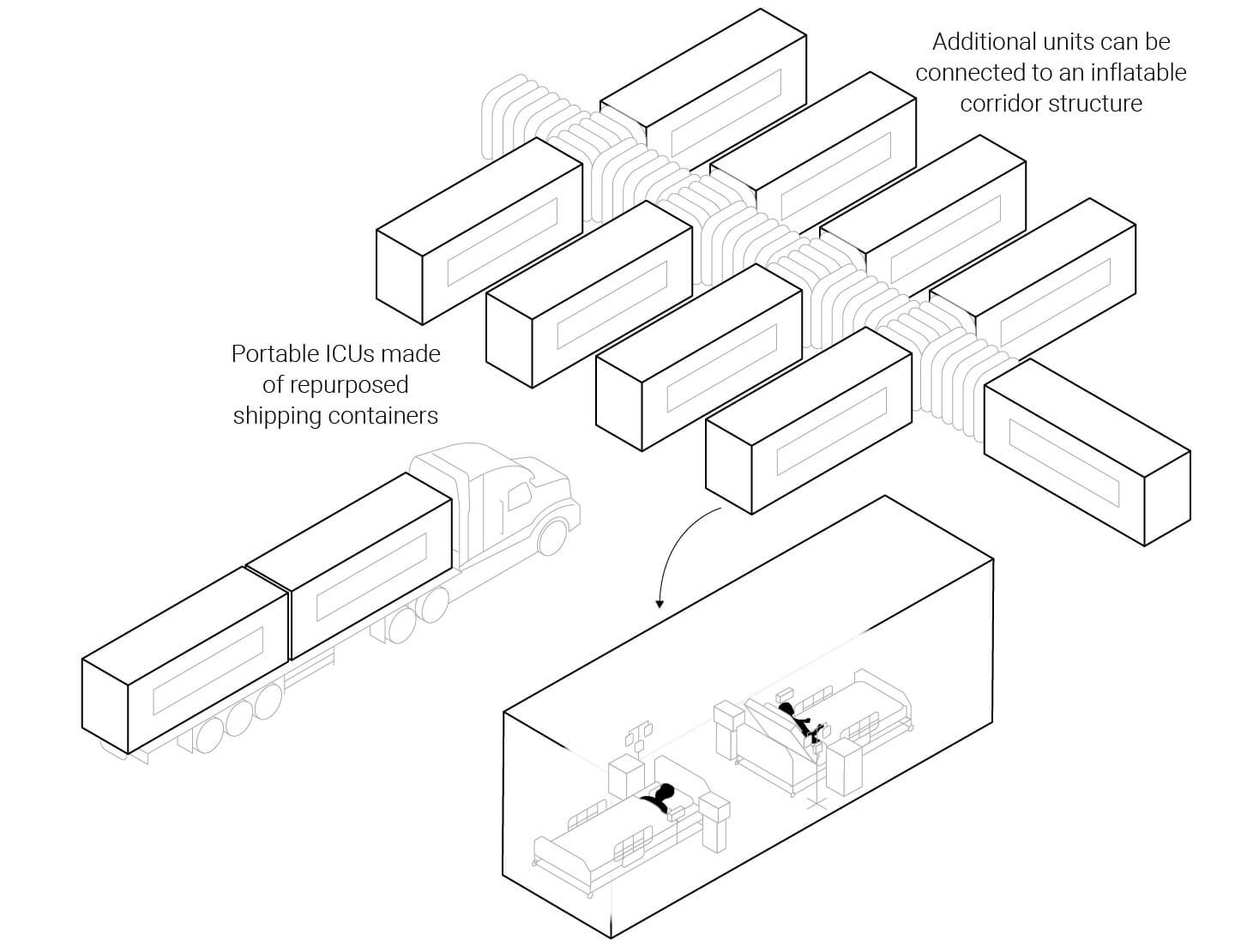

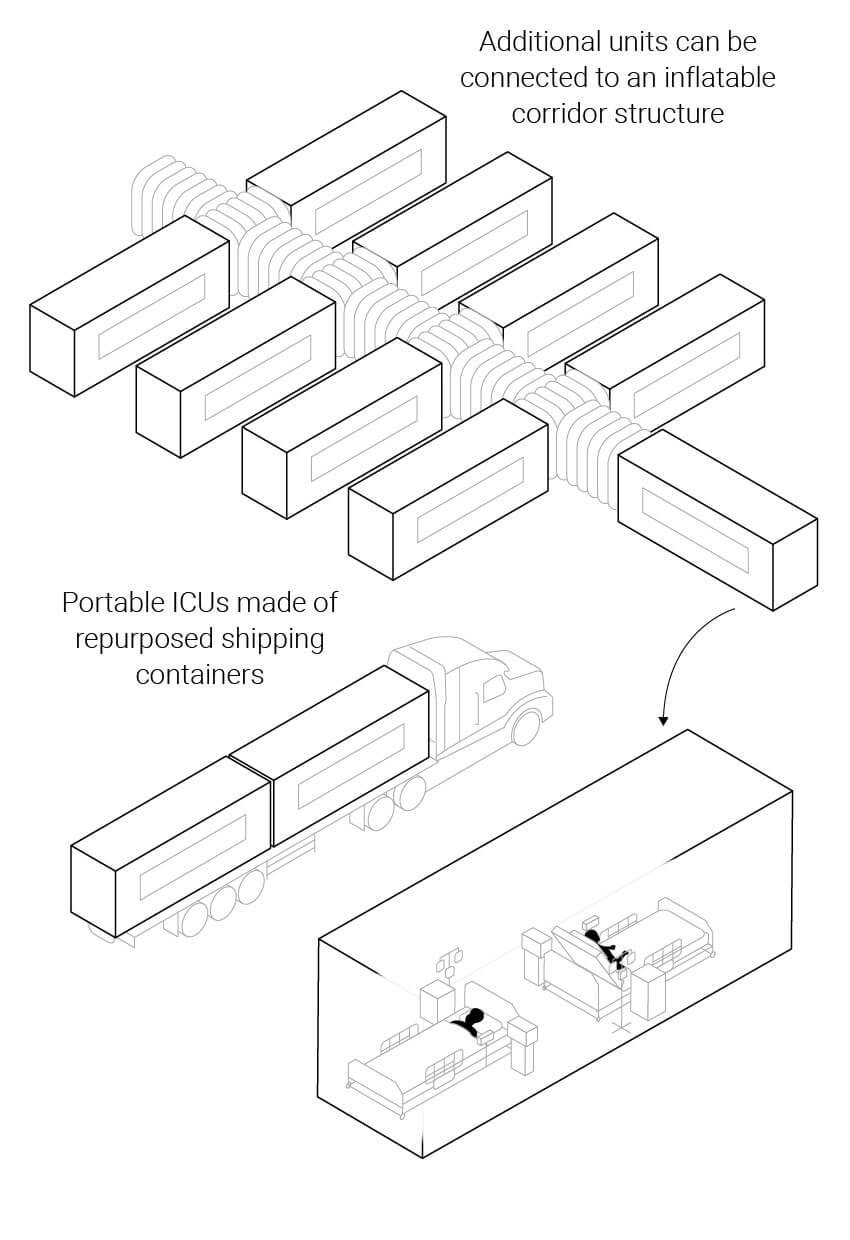

Mobile care units: In Italy, ground zero for Europe’s outbreak, two designers created a mobile intensive-care pod called CURA, which is short for Connected Units for Respiratory Ailments. The first CURA prototype was built in Milan, Italy in April 2020.

CURA CONCEPT

Airports

The coronavirus pandemic has been the biggest disrupter to air travel in aviation history. When international air travel can return to normal depends on the success of global vaccination campaigns and getting Covid-19 under control. Airport operators have been rolling out enhanced security measures, new boarding protocols and technology designed to make flying safer.

CHANGES AT AIRPORTS

Hover/tap the numbers for information

Urban planning

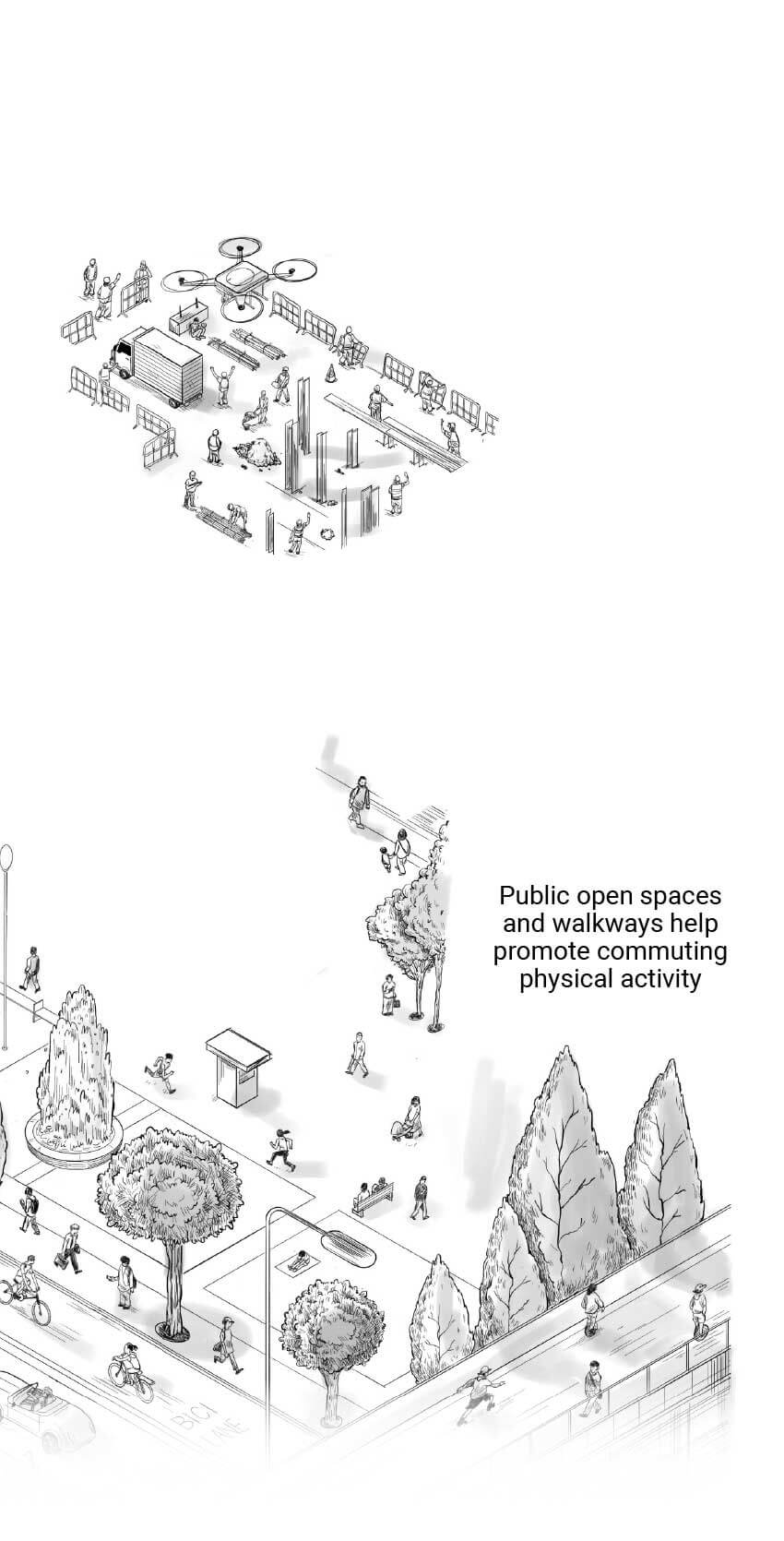

Social distancing can be a challenge in crowded cities. People use public transport and gather in enclosed spaces that can be vectors for viruses. Some of the biggest lessons learned from this pandemic can be applied to urban planning, to help defend our cities from future outbreaks.

Paris, London, Bogota and Hong Kong are among the world’s most walkable cities, according to a 2020 study of nearly 1,000 cities by the New Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP).

“Walkable cities don’t happen by accident,” D. Taylor Reich, the report’s lead author, said. “Policymakers first have to understand the problems that car-oriented planning has caused. Then they can take specific steps: from planning dense, human-scale, mixed-use developments to equipping streets with benches, wide sidewalks and shade.”

Creative Director Darren Long

Edited by Andrew London and Tom Eves

Illustrations by Brian Wang, Adolfo Arranz, and Dennis Wong

Sources: Gensler, Archinect, Dezeen, United Nations