The unique architecture of the Forbidden City

chapter 3

Protecting the imperial seat from fire, earthquakes and time

A PREVIOUS VERSION OF THIS GRAPHIC WAS PUBLISHED ON AUGUST 2, 2018. IT HAS BEEN UPDATED AND WAS REPUBLISHED ON OCTOBER 10, 2025.

Marco

Hernandez

Constructed almost entirely of wood, the Forbidden City's greatest and

most constant threat was fire. Facing perpetual risk from both

accident and sabotage, the imperial court created a sophisticated

defence system. This comprehensive plan included vast bronze water

cauldrons and specialised guards, addressing a threat considered more

immediate than the ravages of time or earthquakes.

While burning torches and lamps inside the palace posed an obvious risk, leading to strict protocols and guards, the main structural threat was lightning. The Forbidden City's taller buildings, in particular, were vulnerable; the Hall of Supreme Harmony, for instance, famously caught fire after a lightning strike just 100 days after its inauguration.

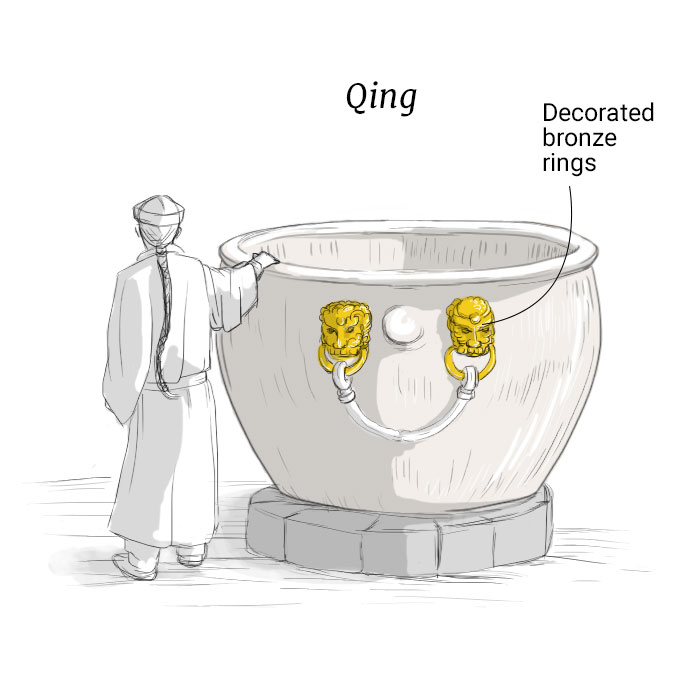

Water defence

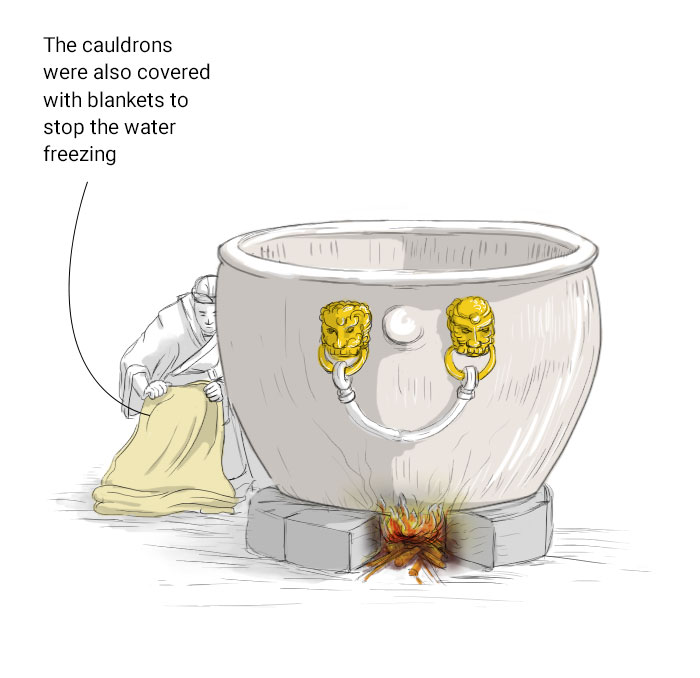

A key fire precaution was the network of 308 iron and copper vats storing rainwater, positioned throughout the complex. These vats were also cultural artefacts, with styles ranging from the simple rings of the Ming dynasty to the elaborate animal-shaped bronze rings and sumptuous gold inlays of the Qing period.

Because the city moat often froze in winter, special measures were taken to keep the vats operational: they were placed on stone blocks beneath which small fires were lit, ensuring a readily available water supply year-round.

Preserving the woodwork

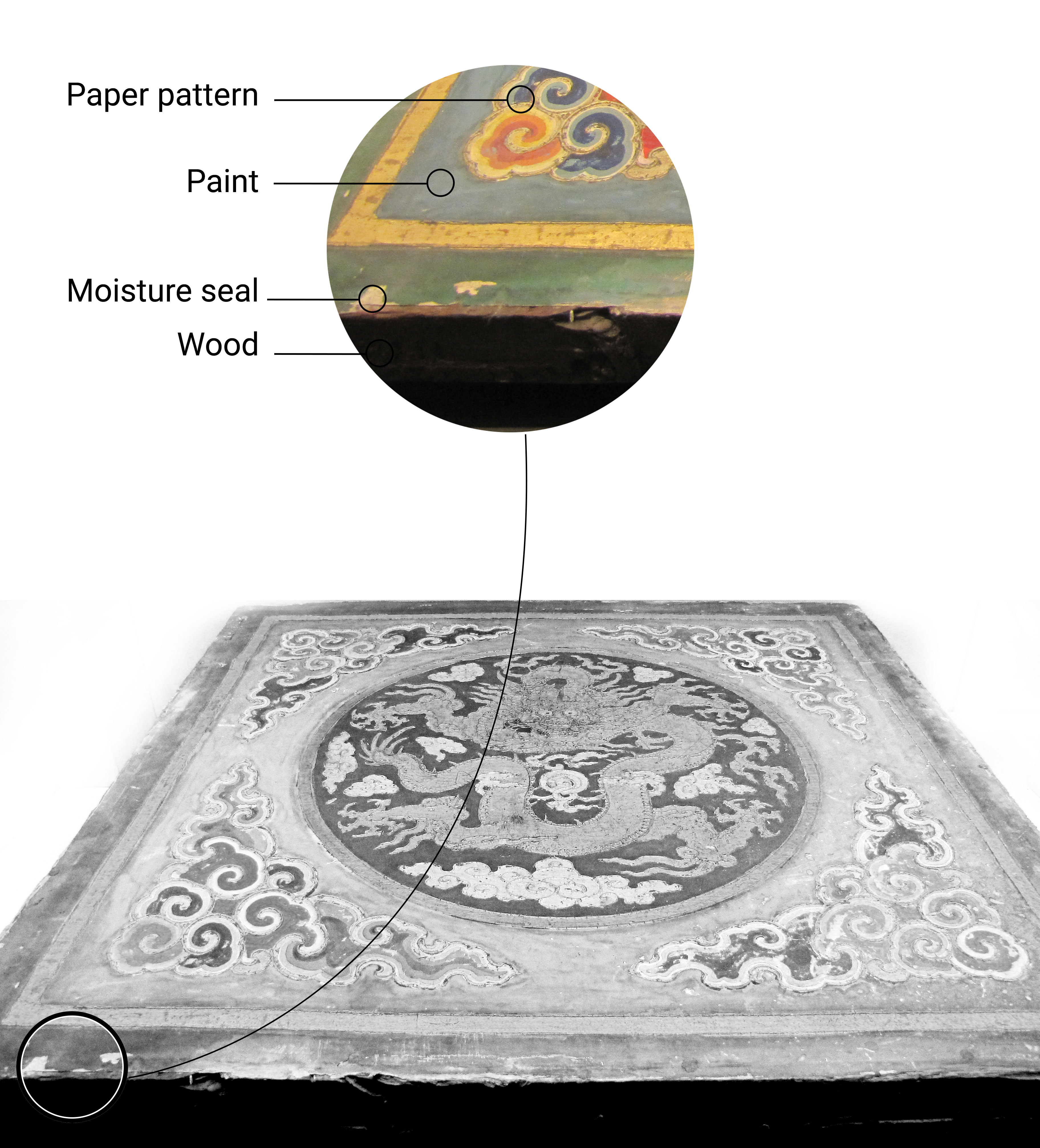

Preservation of the wooden structures was paramount. While major buildings have been restored or rebuilt over the centuries due to damage from fire, conflict and time, many smaller structures remain intact after hundreds of years.

The aesthetic designs of the artisans were not merely decorative; they also served to seal and protect the wood. Purpose-made paint was applied in layers, and patterned paper was used to help safeguard the surfaces.

Seismic resilience

The Forbidden City’s construction also had to account for seismic activity. Unlike modern architecture that avoids heavy roofs, Chinese architects at the time achieved stability in top-heavy buildings through the principle of even weight distribution using pillars.

SEISMIC ACTIVITY IN THE REGION

Beijing has 15 major active fault lines, according to a 2021

geological survey commissioned by the government. The entire area is

squeezed by opposing forces from the Eurasian and Pacific plates,

with most of the resulting stress concentrating in the active

faults. While Beijing’s old town (including the Forbidden City and

Temple of Heaven) lies on or near fault lines, these fractures are

very old, with some quiet since the age of the dinosaurs, and are

believed to be inactive.

Beijing has a long history of seismic activity, experiencing nearly

600 earthquakes since records began 1,700 years ago, with dozens

estimated to have exceeded magnitude 7. Notably, on September 2,

1679, an estimated magnitude 8 earthquake struck the Pinggu

district, killing tens of thousands. Furthermore, Beijing is

surrounded by other major fault lines, such as the one responsible

for the 1976 Tangshan earthquake less than 200km (124 miles) south,

which killed over 240,000 people, making it the second deadliest

earthquake in the 20th century.

Chinese scientists have studied the resilience of old buildings like those in the Forbidden City. In one, they created virtual models and exposed a 1:5 scale model to a simulated magnitude 9.5 earthquake to test the buildings’ resistance. The research concluded that flexibility was the key factor enabling the wooden structures to remain standing.

-

-

Traditional Chinese construction is designed so that the weight of the roof is absorbed like a tree’s branches connecting to the trunk, meaning the walls do not bear the structure’s weight.

-

Building response to quakes

Under seismic forces, the buildings respond with large and violent displacement but remain stable due to this unique weight distribution and flexibility (a principle heavily reliant on the dougong bracket system). Even without the walls, the core framework can withstand the forces.

FURTHER READING

We invite you to explore other chapters of this special Post

presentation for a glimpse into a unique part of Chinese history.

The Palace Museum

By the South China Morning Post graphics team

-

I

PARTThe Forbidden City’s unique architecture

By Marco Hernandez

-

II

PARTLife inside the Forbidden City

By Marcelo Duhalde

-

III

PARTThe collection, the odyssey of the objects

By Adolfo Arranz