Explore the virtual watchtower

Voice: Naomi Ng

VR/360: Marco Hernandez

A PREVIOUS VERSION OF THIS GRAPHIC WAS PUBLISHED ON JULY 26, 2018. IT HAS BEEN UPDATED AND WAS REPUBLISHED ON OCTOBER 10, 2025.

Marco

Hernandez

Even today, it sounds like a near impossible task: how do you build a sturdy, earthquake-resistant wooden building strong enough to endure centuries without using a single nail or any glue? Chinese carpenters rose to this challenge more than 600 years ago.

ELEVATING THE DUOGONG PRINCIPLE

One of the most instantly recognisable aspects of Chinese architecture is roof design. These visually compelling and highly complex structures use the dougong system: a durable and quickly assembled technique involving interlocking wooden joints set into columns and pillars.

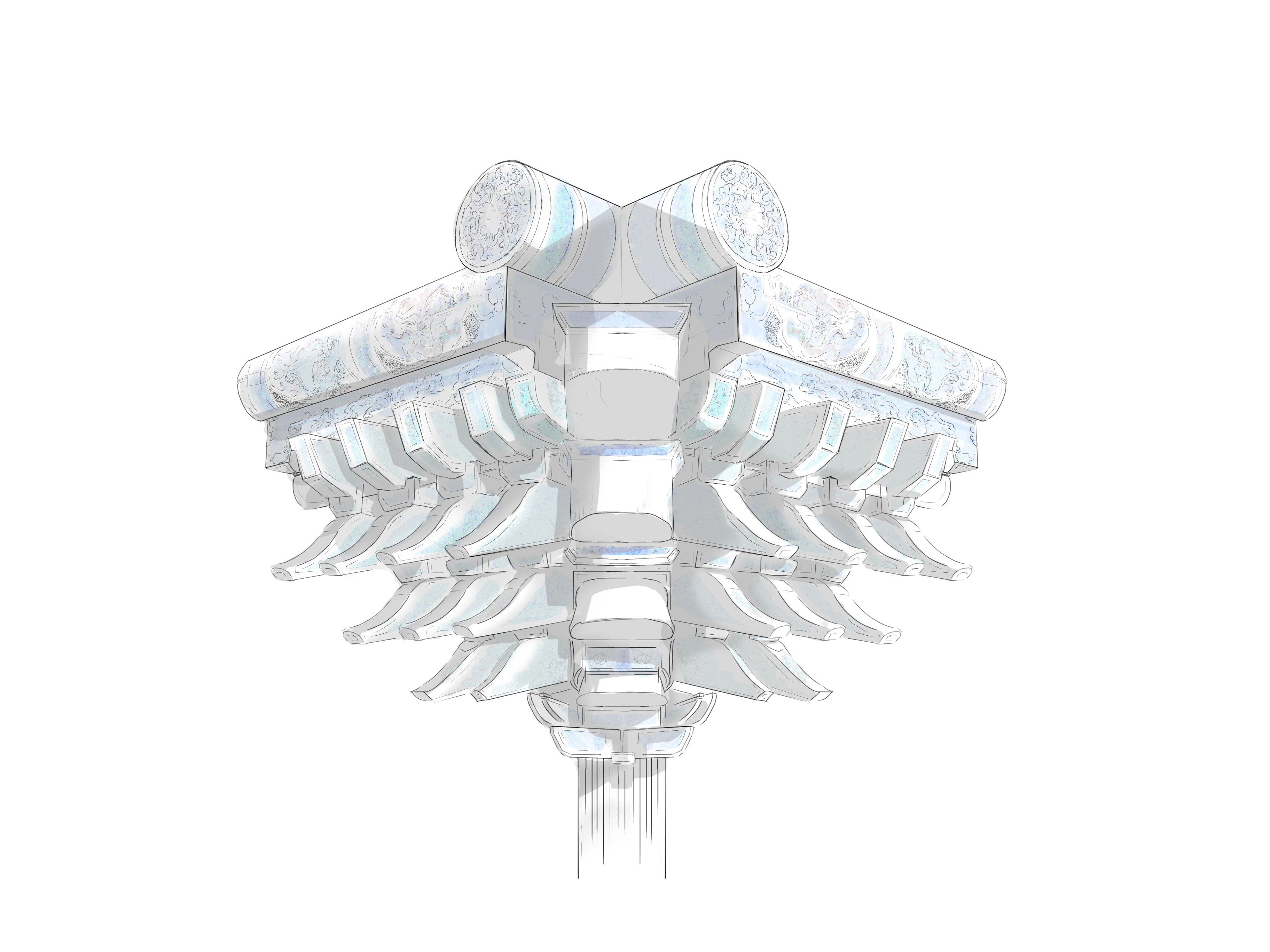

A corner section supporting a Palace Museum roof.

The system is built from interlocking components:

a wooden block (dou) is placed on a column to form a base, and a bracket (gong) is then inserted into the dou to support a beam or another gong.

As multiple brackets are added, the roof's weight compresses the joints, distributing stress evenly throughout the structure. This protects individual elements from splitting or cracking and ensures the system cannot be shaken apart or shattered under stress.

Adding new layers of brackets on top means the dougong pieces need to be slightly modified. There are about 30 combinations with simple variations used to create different structures, but the core principle remains identical throughout. Critically, the system creates an incredibly robust structure that sits lightly on the floor without needing to be sunk into the ground.

During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), variations on the basic dougong shapes allowed for taller and more decorative structures. It was traditionally believed that the greater the number of bracket layers, the more superior the building.

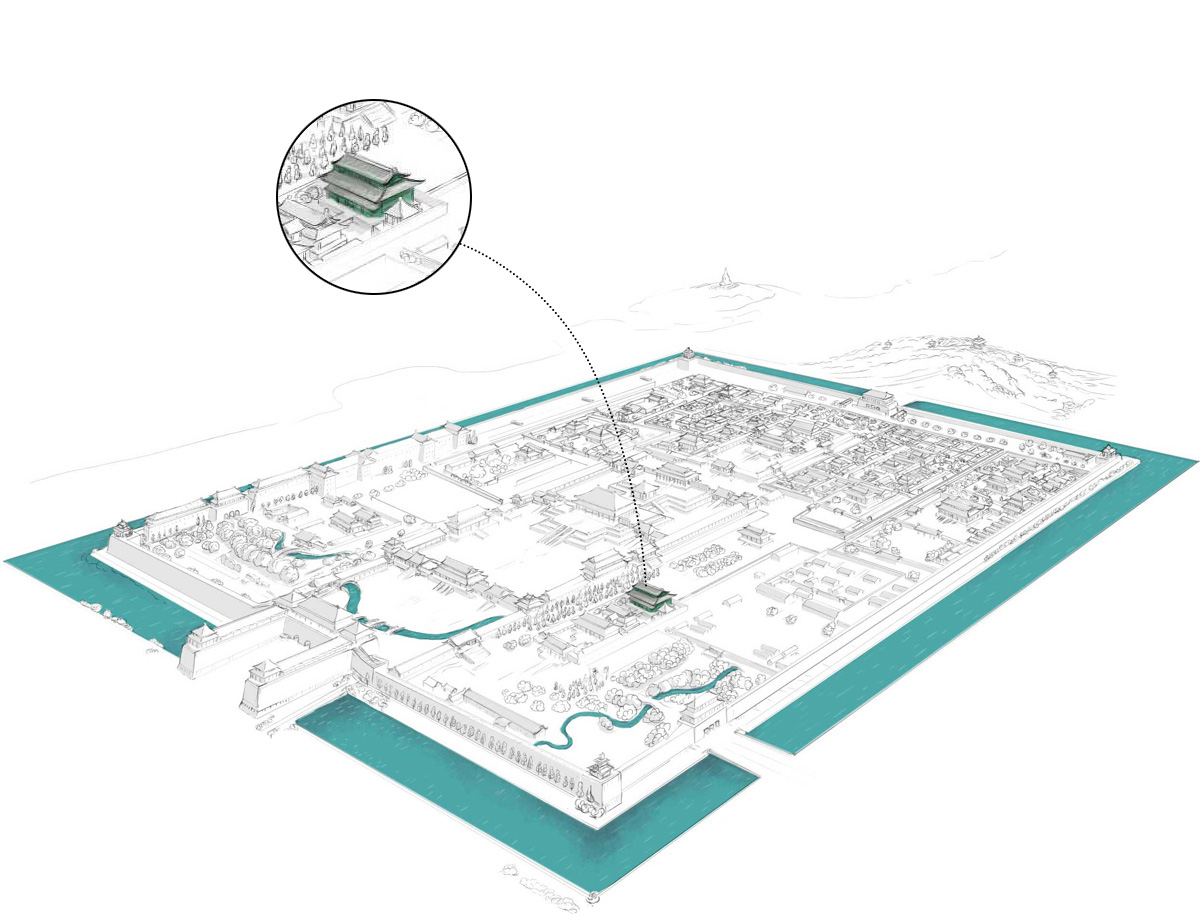

LEGEND OF THE CORNER TOWERS

Strategic observation points were built at each corner of the Forbidden City for protection. These towers are among the most intricate structures in the complex, a design befitting their crucial function.

Palace Museum tour guides often share the tale of the corner towers’ origin: the emperor gave his head eunuch three months to design stunning towers - or face execution.

Realising he would fail, the eunuch spent his final night making a cage for his pet cricket. The emperor was so enamoured with the cricket cage’s design that the eunuch’s life was spared and the corner towers were built in its image.

360 VIDEO

Voice: Naomi Ng

VR/360: Marco Hernandez

THE HIERARCHY OF ROOF STYLES

The distinctive shapes of Forbidden City roofs were highly regulated. Some styles were reserved solely for the Imperial Palace, with common citizens banned from building anything similar. Of the different roof shapes associated, one of the most distinguished is the use of upward-curving corners.

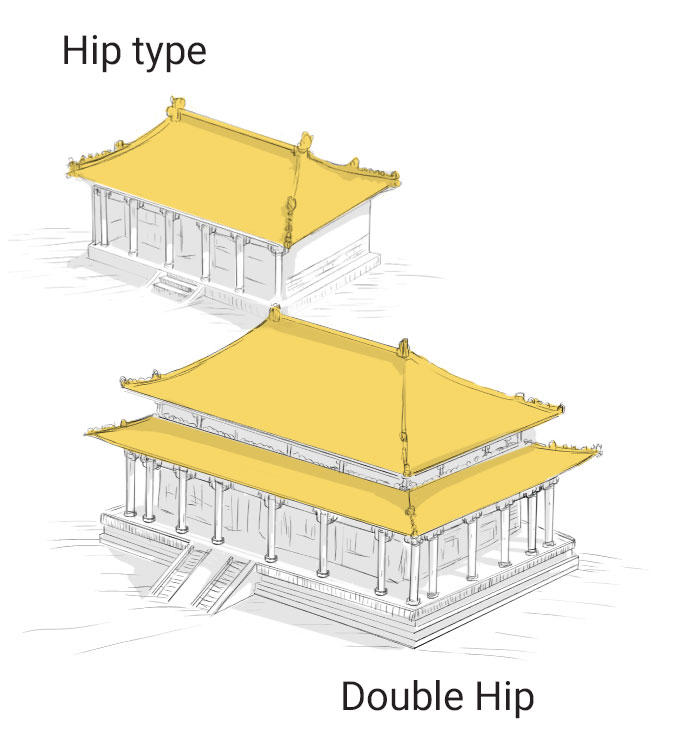

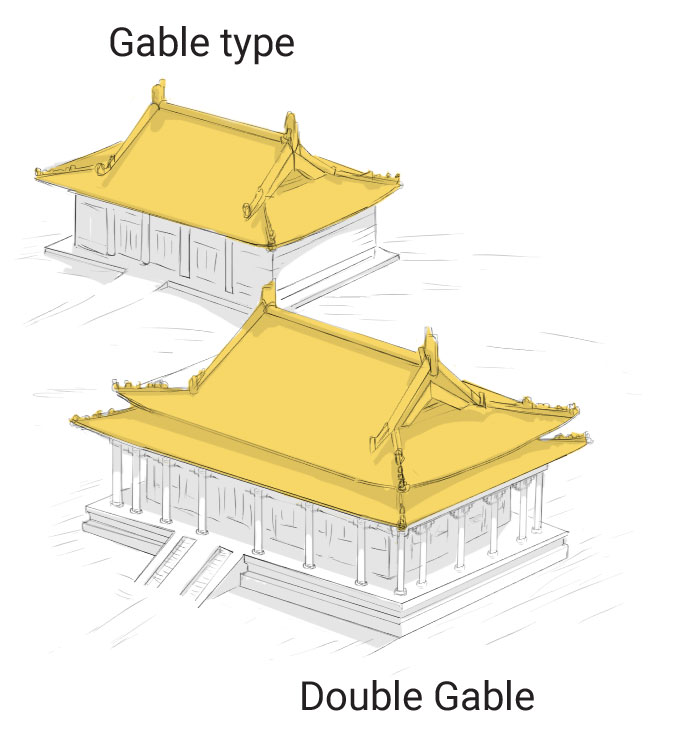

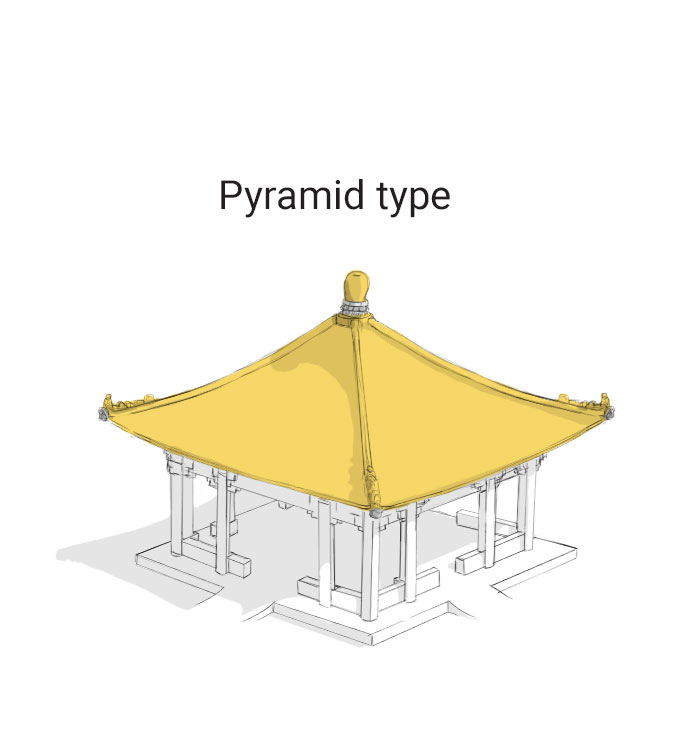

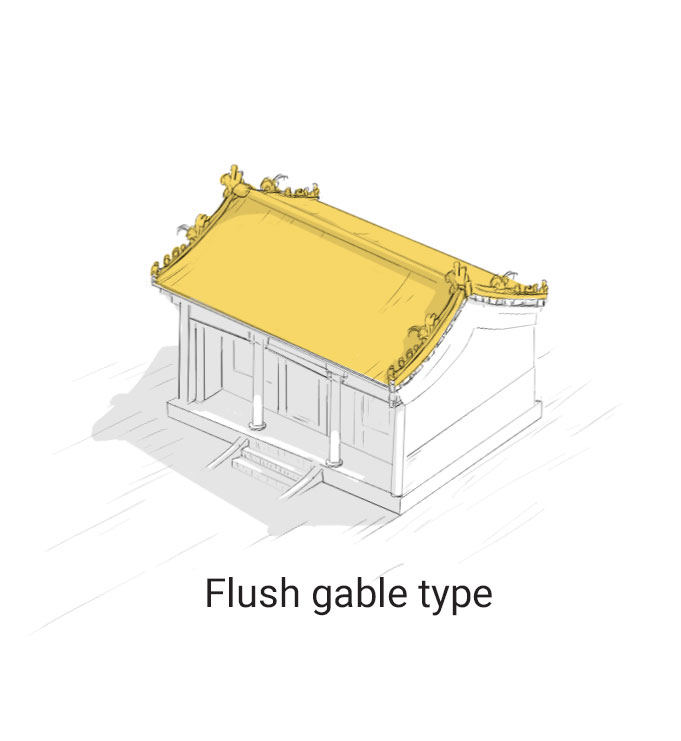

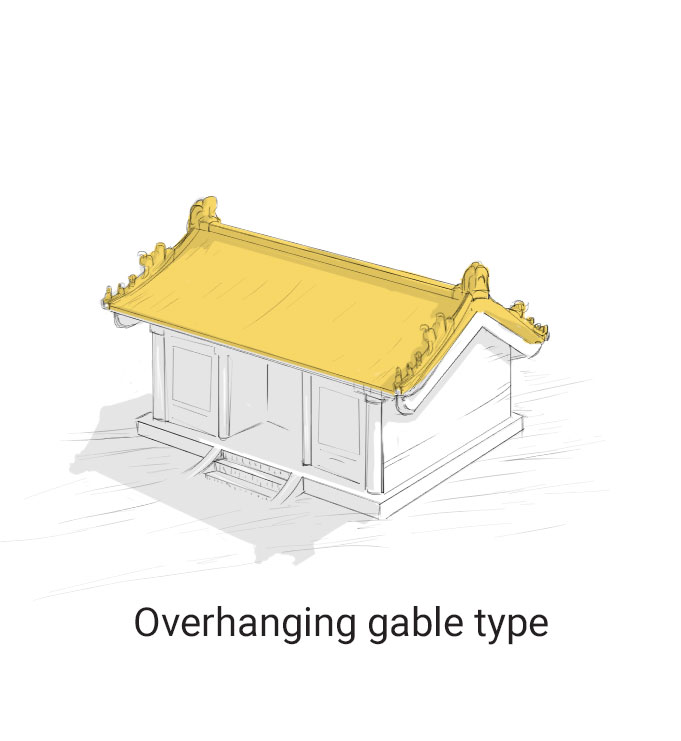

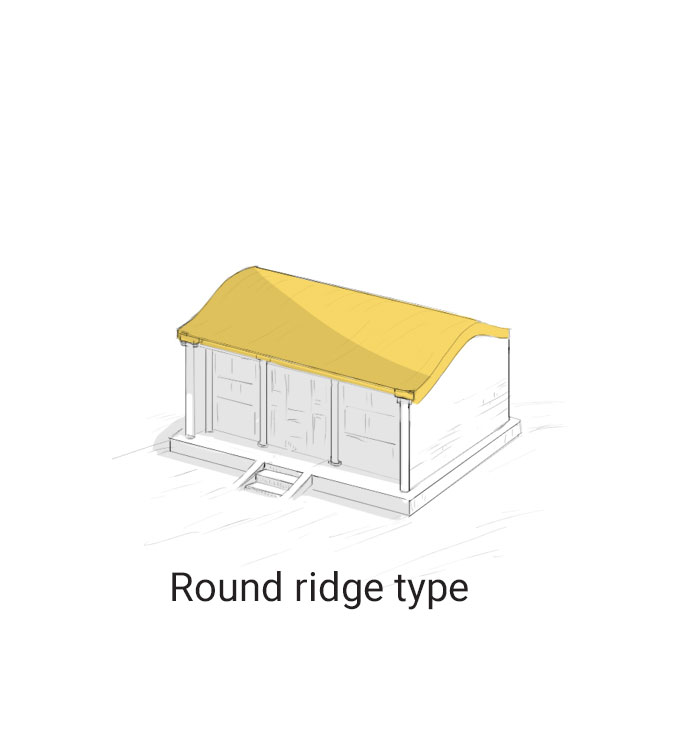

Here are examples of the different types of roofs.Their shapes were determined by the building’s purpose, rank, and the role of the people housed there.

Single or double hip roofs are reserved for the most important buildings. The Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Forbidden City’s main temple, is the highest-grade example of this style.

Single or double gable roofs have nine ridges, in contrast to the five ridges of hip roofs. This style denotes temples or mansions of secondary importance constructed for high-ranking officials.

These four-cornered roofs were typically designated for garden structures and pavilions.

Characterised by the absence of eaves (the roof edges are flush with the wall). This style was primarily used for workers’ houses.

Similar to the flush gable, this style features eaves that overhang the walls. It was commonly used for servants' houses.

These structures were often used in the gardens of summer houses and side halls.

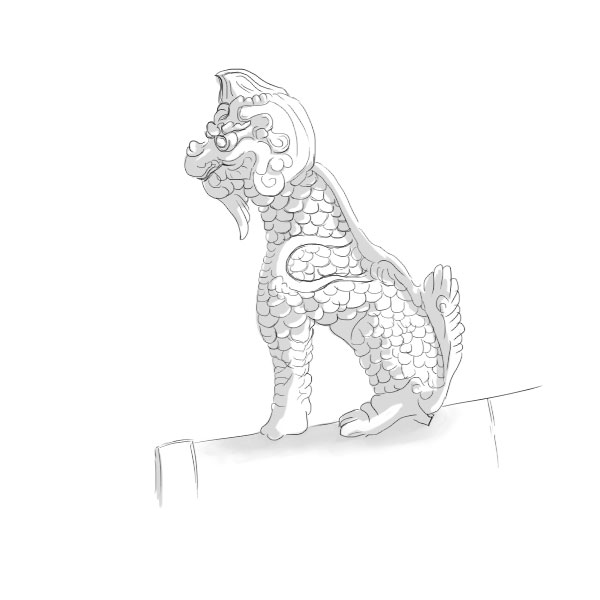

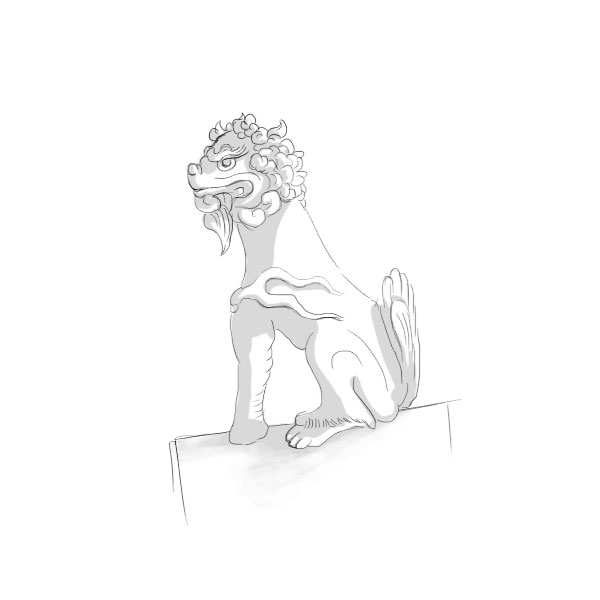

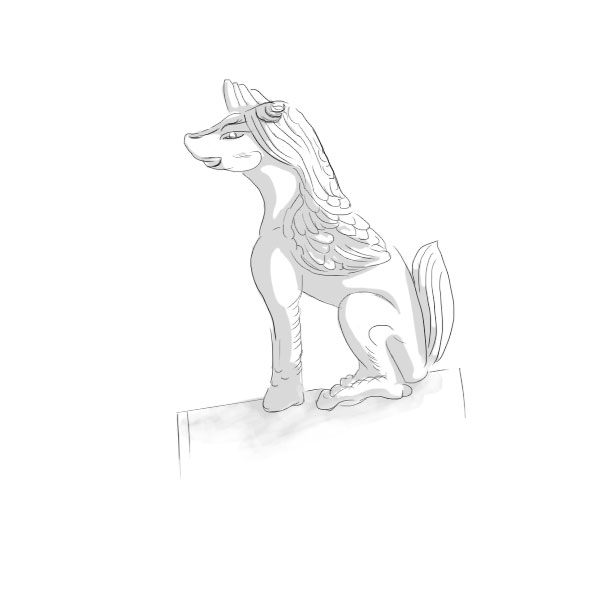

ANIMAL DECORATIONS AND IMPERIAL POWER

Decorative elements are considered essential and potent features in Chinese folklore. Mythical creatures like phoenixes and dragons symbolise power, prosperity, or royalty. The Hall of Supreme Harmony, for example, boasts 13,433 individual dragon ornaments.

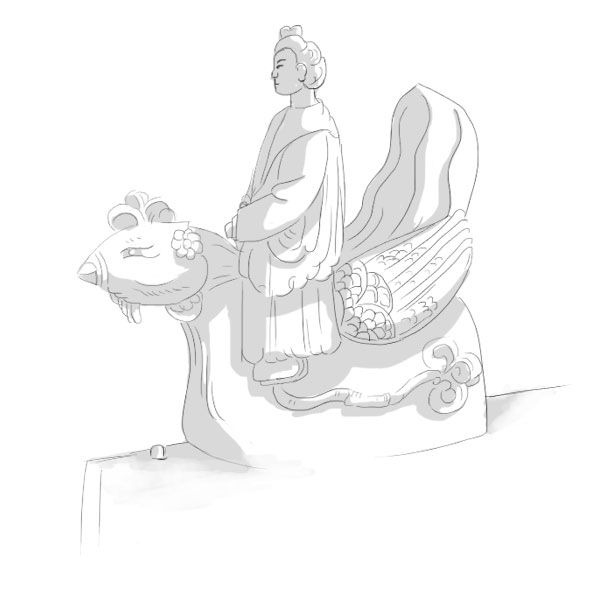

Dragons and other animal ornaments crown the roofs of most of the Forbidden City’s main structures. The ridges are decorated with all manner of clay figures, following a strict rule: the more important the building, the greater the number of figures.

Always at the front of the line, this figure is meant to inspire hope.

The most honourable of heavenly beasts, positioned second.

The king of all birds.

The king of all animals.

According to tradition, this beast can travel 1,600km (1,000 miles) in a day.

Considered a creature full of courage and power.

The incarnation of the dragon’s offspring.

Capable of summoning winds and storms.

A beast that is part-goat, part-bull. Mythology considers it righteous and keen to attack liars.

This figure dispels evil and is said to eat clouds to exhale mist.

Traditionally called the son of thunder, this beast is closest to the top of the roof. It is only present on the Hall of Supreme Harmony.

Factories for ornamental figures, bricks, and tiles were built on the borders of Beijing to keep the smoke from kilns away from the Imperial Palace. Amazingly, some of these factories were producing these materials hundreds of years later.

Distinctive glazes were applied to the ceramic figures that decorate the roofs. This chemical process made the figures more durable and added vivid colours to the sculpted models. Firing the clay is a critical part of the ceramic process because it is what makes the clay durable.

The clay is given a wash - a mixture of oxides and water - before it goes into the kiln.

IMPERIAL COLOUR SYMBOLISM

Symbolic meanings are applied throughout Chinese culture, and colour is no exception. Red walls symbolise prosperity and good fortune, but also fire. To counter the risk of fire in the library, builders took no chances: the library was painted with green walls and a black roof (black symbolises water).

Yellow roofs symbolise the Earth and supreme power. The palace, therefore, utilises a harmony of primary colours: red for the walls, yellow for the roofs, and blue denoting the sky.

FURTHER READING

We invite you to explore other chapters of this special Post presentation for a glimpse into a unique part of Chinese history.

By the South China Morning Post graphics team

I

PART

By Marco Hernandez

II

PART

By Marcelo Duhalde

III

PART

By Adolfo Arranz

ACCOLADES FOR THIS VISUAL PROJECT

This infographic has earned the following awards:

Wan-Ifra Digital Asian Media Awards

2019 Edition

Society For News Design

Edition 40

Society For News Design

Edition 40

Here are some other digital native projects you might want to visit

Or just visit our graphics home page

This site has some features that may not be compatlibe with your browser. Should you wish to view content, switch browsers to either Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox to get an awesome experience