1406

The Yongle Emperor, Zhu Di, begins plans to build an imperial palace in his new capital, Beijing, four years after overthrowing his nephew from power.

A PREVIOUS VERSION OF THIS GRAPHIC WAS PUBLISHED ON MAY 29, 2018. IT HAS BEEN UPDATED AND WAS REPUBLISHED ON OCTOBER 10, 2025.

Marco

Hernandez

The 14 years spent planning and building the Forbidden City (1406-1420) were defined by painstaking detail: a decade alone was dedicated to designing the Yongle Emperor’s new home. Architects had to account for location, building orientation, and the complex logistics of sourcing, preparing and transporting raw materials.

SHAPES AND SYMBOLISM

The Forbidden City complex was the beating heart of Beijing. The rectangular walled palace was surrounded by two square ring roads that defined and protected the ancient city. As Beijing expanded over the years, square ring roads radiated outwards from the Forbidden City. Even today, the seventh ring road - which links Hebei with Tianjin to form the megacity known as Jingjinji - retains this square orientation, with the palace at the centre.

Traditionally, circles represent perfection due to the Chinese belief that no human could make a flawless circle by hand. In contrast, the straight lines of squares and rectangles are associated with law and order, according to Chinese convention. Cities and official complexes were subsequently planned as rectangles. Housing the head of state at the centre of a walled complex made it easier to protect him and, no doubt, provided his family with a sense of security and well-being.

The orientation of the Forbidden City is centred along a north-south axis, which is about one degree shy of the geographical north. Remarkably, this feat was achieved 150 years before Gerardus Mercator, a German-Flemish cartographer, introduced the first map to accurately project ratios of latitude and longitude. It remains the central axis of Beijing to this day.

FENG SHUI AND PRAGMATIC MYSTICISM

Chinese culture sets great store by the mystical and spiritual, but frequently blurs the lines between metaphor and function. Feng shui is a case in point, as it seeks to balance and harmonise people and buildings with the surrounding environment.

Hierarchy

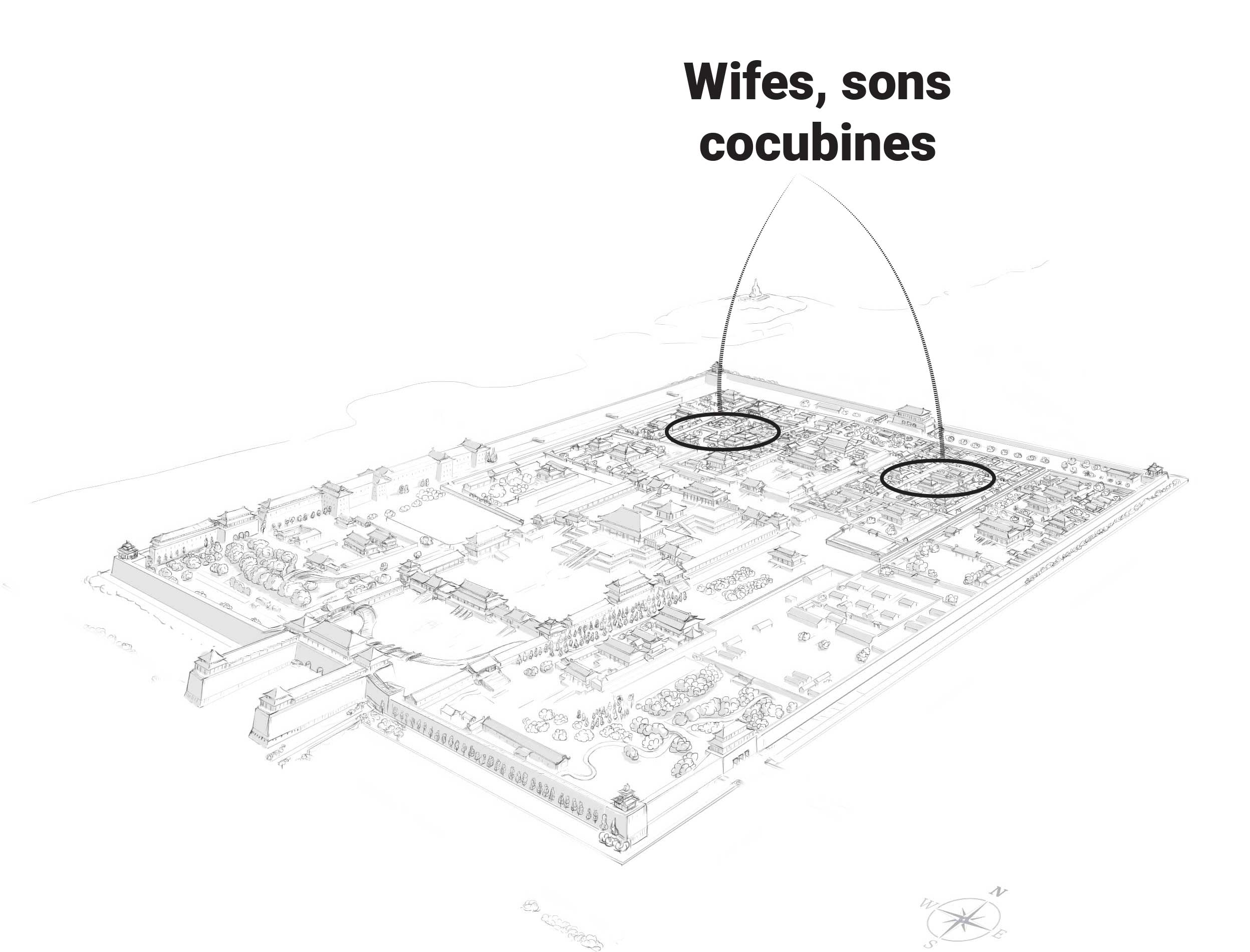

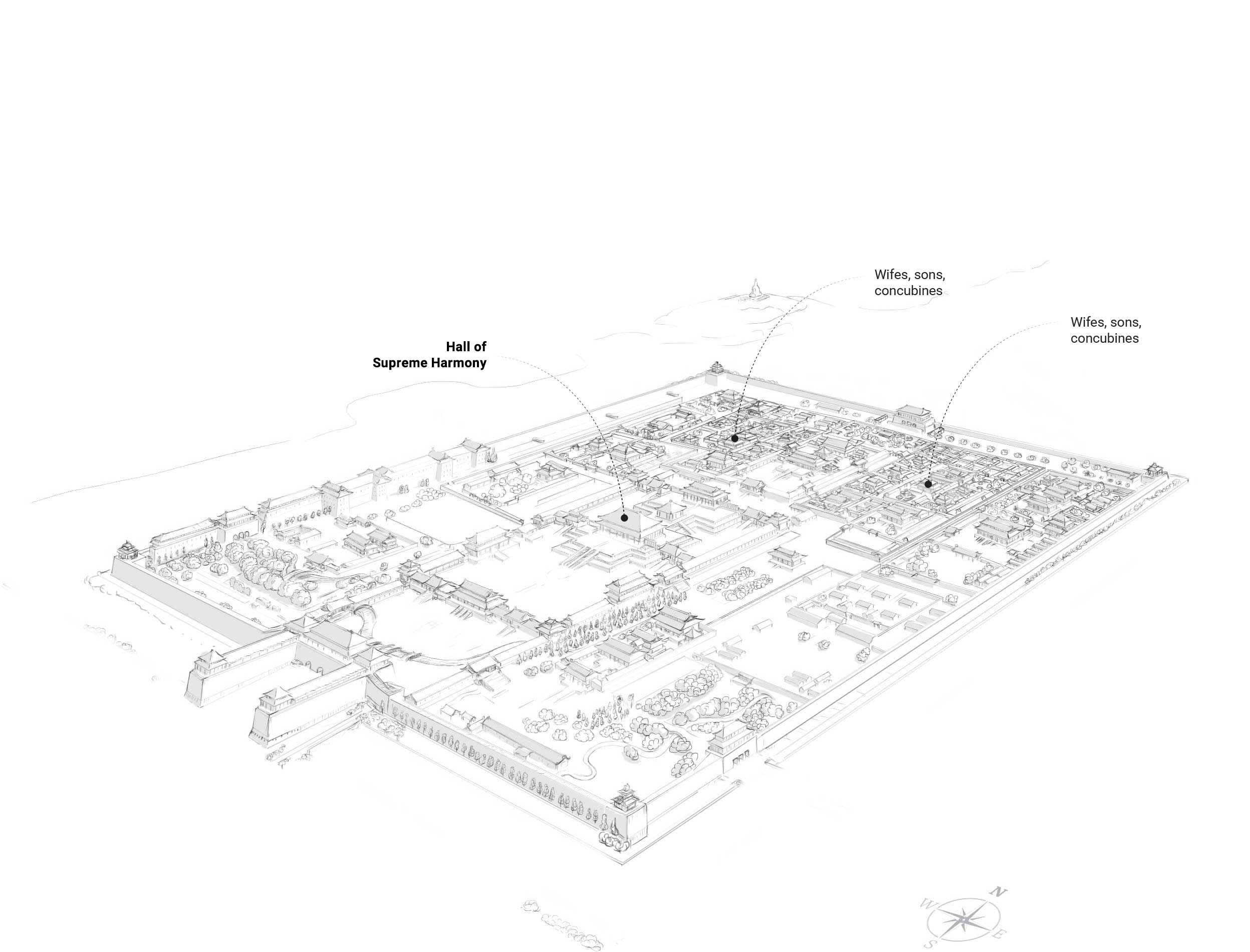

Those among the higher social echelons were housed in the far northern end of the complex, with the area to the south reserved for wives, sons and concubines. Servants were housed closer to the southern sector to receive visitors.

Facing south

The Hall of Supreme Harmony was at the heart of the complex, with the courts designed to symmetrically orbit the hall. All doors faced south so that visiting diplomats could be ushered straight to the Hall of Supreme Harmony.

Sculpting mountains

A total of 29,000 cubic metres of mud was excavated for the moat and used to build a protective hill. According to feng shui principles, this hill - Jingshan Hill, also known as Prospect Hill - restored the balance between water and earth.

Wind protection

The artificial hill behind the city reduced wind currents from the north and served as protection from attack.

THE RISE OF THE PALACE

The Forbidden City is a rectangle with a total area of about 720,000 square metres (7.75 million square feet). The construction phase of the complex was swift, lasting just four years (1416–1420). A total of 100,000 artisans and one million labourers made this feat possible. Here are some key historical events:

Materials used to construct the Forbidden City came from all over China. Timber came from forests in faraway southwest China, and stones from lakes were transported to Beijing to create rock gardens. One of the most astonishing stories concerns the huge engraved stones found in the main entrances to the temples.

ASTONISHING LOGISTICS

Carved stones of various sizes decorate the main entrances to the halls in the Forbidden City. Most of those stones were transported from a quarry 70km (43 miles) away during winter.

Working in average winter temperatures of −3.7 degrees Celsius (25 Fahrenheit), labourers created an icy surface by sloshing water in front of the sled so that the quarried sandstone could be slid over rough ground.

By using sleds, 40 to 50 men could transport a huge stone the 70km distance from the quarry to the palace in as little as 30 days. In summer, the same stone would have taken around 1,500 men at least 40 days using wheeled transportation.

GOLDEN TILES: THE SECRET BEHIND THE NAME

Another special material was prepared in Suzhou: millions of golden tiles. It is estimated that some 100 million tiles were used throughout the Forbidden City, with the courtyards alone requiring 20 million paving tiles.

The floors of buildings frequented by the emperor were of the highest quality. Making these floor tiles was an expensive process. During the Ming dynasty, a single brick cost the equivalent of 750kg (1,650 pounds) of rice, or three months of a magistrate’s salary.

The slow kilning process results in a highly durable material, but surprisingly, given the name, the tile does not resemble gold. The term “Golden Tile” actually refers to the steep cost and time invested in the manufacturing process.

FURTHER READING

We invite you to explore other chapters of this special Post presentation for a glimpse into a unique part of Chinese history.

By the South China Morning Post graphics team

I

PART

By Marco Hernandez

II

PART

By Marcelo Duhalde

III

PART

By Adolfo Arranz

ACCOLADES FOR THIS VISUAL PROJECT

This infographic has earned the following awards:

Wan-Ifra Digital Asian Media Awards

2019 Edition

Society For News Design

Edition 40

Society For News Design

Edition 40

Here are some other digital native projects you might want to visit

Or just visit our graphics home page

This site has some features that may not be compatlibe with your browser. Should you wish to view content, switch browsers to either Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox to get an awesome experience