Life inside the Forbidden City

CHAPTER 1

Life inside the Forbidden City: the women selected for service

A PREVIOUS VERSION OF THIS GRAPHIC WAS PUBLISHED ON JULY 12, 2018. IT HAS BEEN UPDATED AND WAS REPUBLISHED ON OCTOBER 10, 2025.

Marcelo

Duhalde

All females within the Forbidden City were strictly sequestered in

the imperial quarters (the inner court), forbidden from venturing

outside the northern section of the palace. The women of the inner

court - composed of concubines, palace servants, and royal princesses

- served distinct roles. Most were employed as maids and servants,

while concubines were specifically selected to bear children for the

emperor. Those who successfully gave birth to male offspring could be

elevated to imperial consorts, with the empress holding the supreme

position within this strict hierarchy.

Concubines

Selecting partners

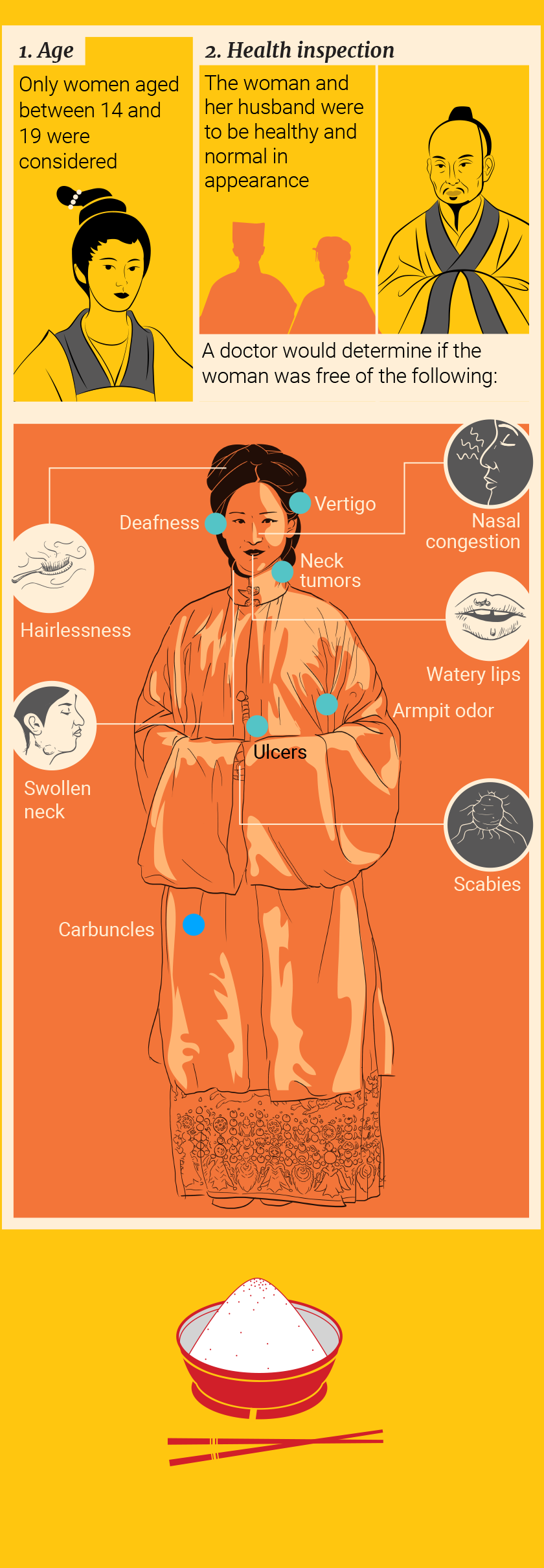

Women selected for court were known as xiunu (elegant females), with selection criteria varying by emperor. In the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), for example, no household was exempt: all young unmarried women were required to go through the xiunu selection process, with only married women or those with certified disabilities being exempt.

The Qing Emperor Shunzhi (1638-61), however, began to limit selection primarily to “Eight Banners” families (mainly Manchurian and Mongolian), thereby excluding most of the Han population.

The process was bureaucratic: the Board of Revenue notified officials and clan heads to gather lists of eligible females. Banner officials then submitted the lists to the commanders’ headquarters in Beijing and the Board of Revenue, which set the final selection date.

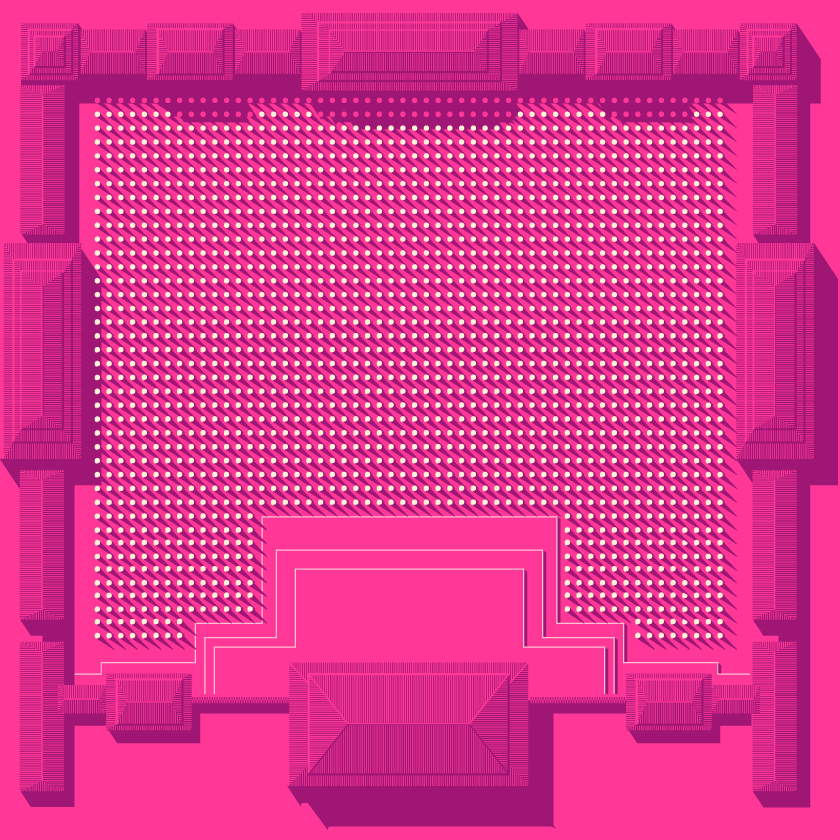

REQUIREMENTS FOR SELECTION

On the appointed

day during the Qing dynasty, girls accompanied by relatives, clan

heads, and local officials - were brought to the

Shenwu (Martial Spirit)

Gate of the Forbidden City for inspection.

During the first round of selection, women stood in

lines of 100, according to age.

As many as 1,000 were eliminated for being too tall,

short, fat or thin.

The next day, eunuchs intensively examined bodies, voices, and general manner, eliminating another 2,000.

The third day focused on observing their feet, hands, and grace of movement, eliminating another 1,000.

The remaining 1,000 underwent gynaecological examinations, dismissing another 700.

The remaining 300 were housed for a month-long series of tests for intelligence, merit, temperament and moral character.

The top 50 candidates were subject to further examinations and interviews on subjects like maths and literature, and were ranked accordingly.

The three favourites would receive the highest ranking for imperial concubines.

Only a few of those who survived this rigorous process would win the emperor's favour. The resulting politics and jealousy were rife among concubines, with many spending their lives in bitter loneliness. For some, beauty was more of a curse than a blessing.

ACTIVITIES

Concubines were strictly

forbidden from having sex with anyone other than the emperor.

Most of their activities were overseen and monitored by eunuchs, who wielded great power in the palace. Concubines were required to bathe and be examined by a court doctor before sex with the emperor.

With hundreds, and sometimes thousands of concubines available, anyone the emperor visited was subject to jealous rivalries. Concubines filled their days applying make-up, sewing, practising various arts, and socialising. Many spent their entire lives in the palace without ever meeting the emperor.

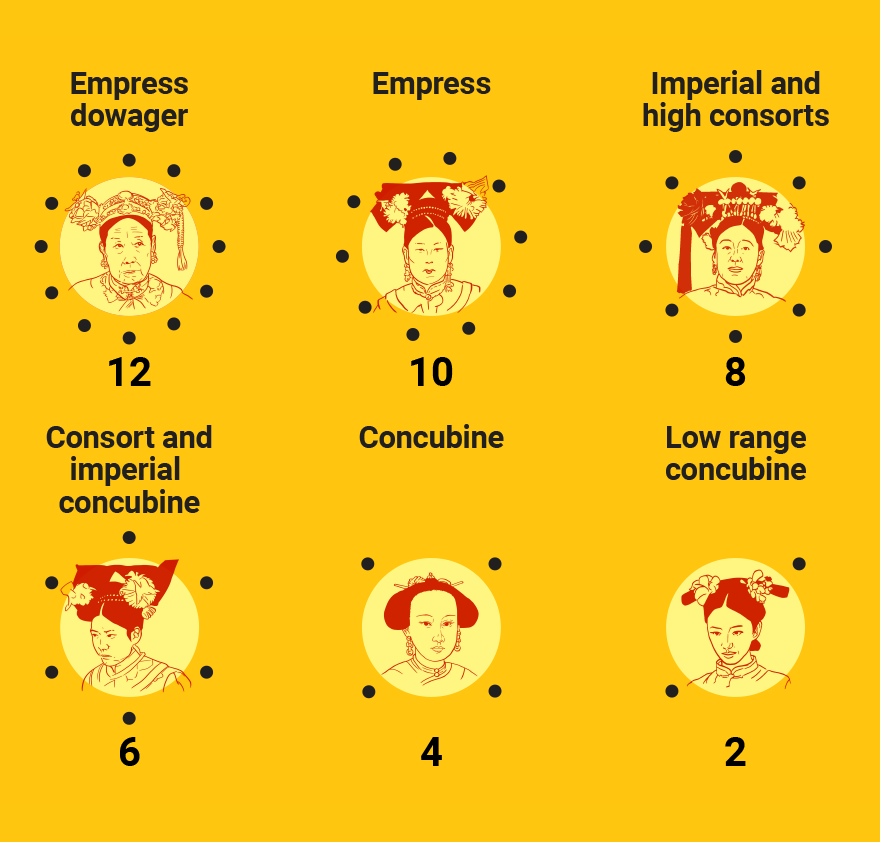

HIERARCHY

Qing dynasty harem system

The ranking of

consorts and concubines remained consistent, though the number

varied among different emperors.

POLYGAMY

Common among the upper and wealthy

middle classes in feudal China, polygamy was primarily a sign of

male potency and was strongly focused on procreation to ensure the

family name continued.

The Confucian principle of daxue (great learning) tied a man’s personal growth to his ability to manage a family. For the emperor, this mandate was critical, making guaranteeing a successor the most paramount concern.

1. Strict distinction

The main wife (empress) was superior to all others and was responsible for mentoring them in harmonious behaviour for the greater good.

2. No jealousy

Women were expected to rise above negative emotions like bitterness, jealousy and rivalry.

3. No attachment

The emperor should not have a favourite, and wives should not monopolise the man. Passionate attachment was unacceptable, as favour had to be distributed evenly.

4. Strict hierarchy

Each dynasty established ranks for imperial wives. A wife’s position was determined at specific times, such as when she first joined the imperial family and was assigned a rank.

EMPEROR’S SEXUAL ROTATION

It was believed

that regulating the emperor’s sex life was essential for the

well-being of the entire Chinese empire. To enforce this, the

rotation of concubines was kept strictly regimented. Curiously,

10th century Chinese calendars were used not for general

timekeeping but specifically to manage this royal sex schedule.

Secretaries documented every encounter, recording the emperor’s

sexual life with brushes dipped in imperial vermilion.

MOON CYCLE

The Imperial Chinese believed

that conception was most likely during the full moon, when the

yin (female influence) was

strong enough to match the

yang (male force) of the

emperor. This belief strictly determined the schedule: the empress

and high-ranking wives slept with the emperor around the time of

the full moon, as it was believed children of strong virtue would

be conceived then. Conversely, lower-ranking concubines were

tasked with nourishing the emperor’s

yang with their

yin, sleeping with him

around the time of the new moon.

THE FATE OF A FAVOURITE

Zhenfei (the “Pearl Consort”) entered the palace in 1899 at age 13 and soon became the Guangxu Emperor’s favourite consort, gaining significant influence. Her beauty, intelligence and rebellious nature - particularly when it came to royal rules and regulations - infuriated Empress Dowager Cixi.

Their conflict reached a climax on June 20, 1900, as the Eight-Nation Alliance laid siege to Beijing. As Cixi forced the emperor to flee, she ordered Zhenfei to commit suicide, falsely claiming her presence would endanger the royal party. When Zhenfei refused, Cixi is believed to have ordered eunuchs to seize her and throw her down a well behind the Ningxia Palace.

Palace servants

The Qing Palace maids

Maids were female servants recruited exclusively from Eight Banners families (mainly Manchurians and Mongolians) at the age of 13. Their role was to attend constantly to the daily needs of the empress, consorts and concubines, remaining by their ladies' sides seven days a week. The maid-in-waiting held the highest rank.

MAIDS ASSIGNATION

The number of maids

assigned varied based on the rank of the women they served.

WET NURSES

Wet nurses gained prominence because imperial consorts and concubines wished to mark their high status by sparing themselves the physical challenges of breastfeeding.

THE SELECTION

The Rites and Proprietary office tasked eunuchs with the unusual responsibility of recruiting 20 to 40 lactating women every three months.

When a baby was due, 40 wet nurses and 80 substitutes were employed. To ensure the balance of yin and yang and prevent any substitution, a crucial rule was observed: imperial sons were breastfed by nurses whose own child was a girl, and imperial daughters were breastfed by those whose child was a boy.

REQUIREMENTS

When working, wet nurses received a clothing allowance, a daily ration of rice and meat, and coal during cold weather.

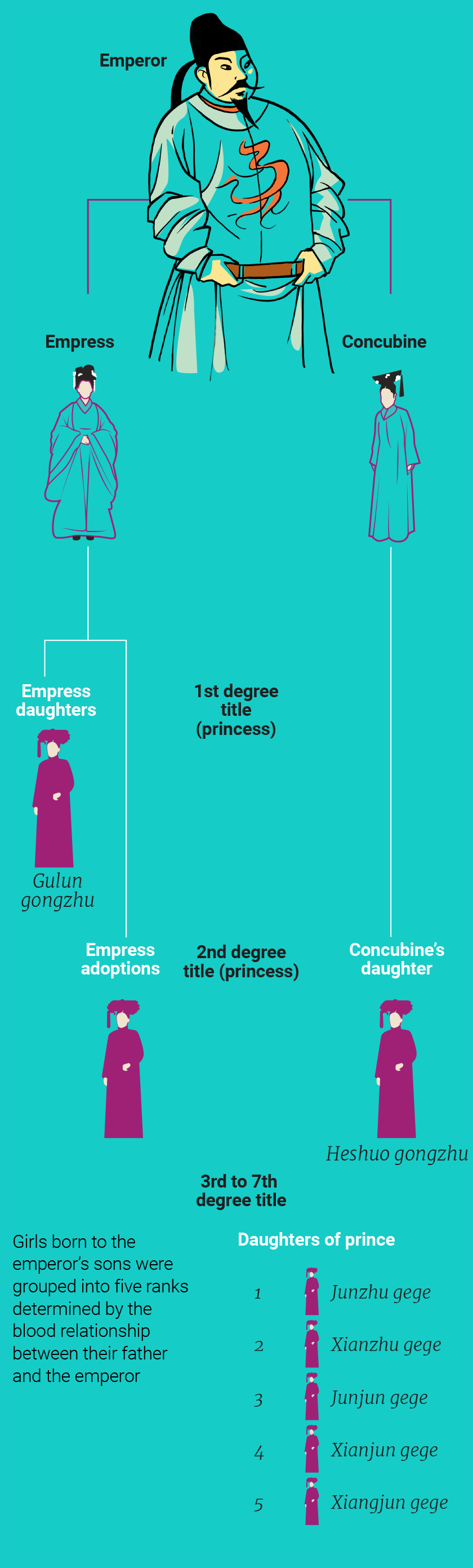

Royal princesess

Women in the imperial family

The emperor’s unmarried female relatives were required to live within the inner palace.

RANK METHODOLOGY

Imperial daughters were

ranked according to their bloodline to the emperor and their

mother’s title.

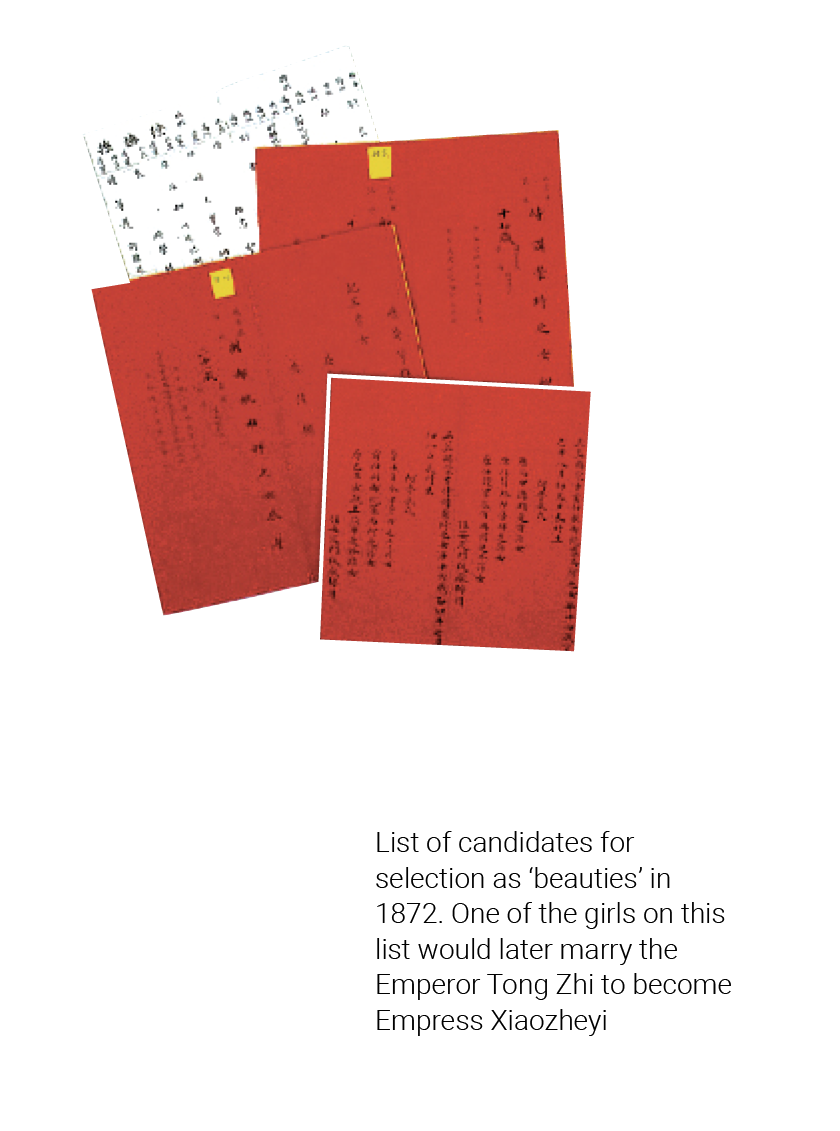

THE OTHER WAY TO BECOME A NOBLE

The same

pool of xiunu (beauties)

from the Eight Banners families was also used to find wives and

concubines for other male nobility. Candidates were presented in

small groups. Those selected would become palace concubines, or be

married to the emperor’s sons, grandsons, princes, and dukes.

Empresses were often chosen from this high-ranking group of

“beauties”.

FURTHER READING

We invite you to explore other chapters of this special Post

presentation for a glimpse into a unique part of Chinese history.

RELATED STORIES

China’s Qing dynasty empresses, their lives and power they wielded, take centre stage at US show

The Chinese scholar who threw himself in a well, and the palace consort ‘martyred’ in one

‘So beautiful fish forget to swim’: ‘Four Beauties’ of ancient China changed nation’s history

Reflections | How Chinese princes lived lives of privilege and precariousness

The Palace Museum

By South China Morning Post graphics team

-

I

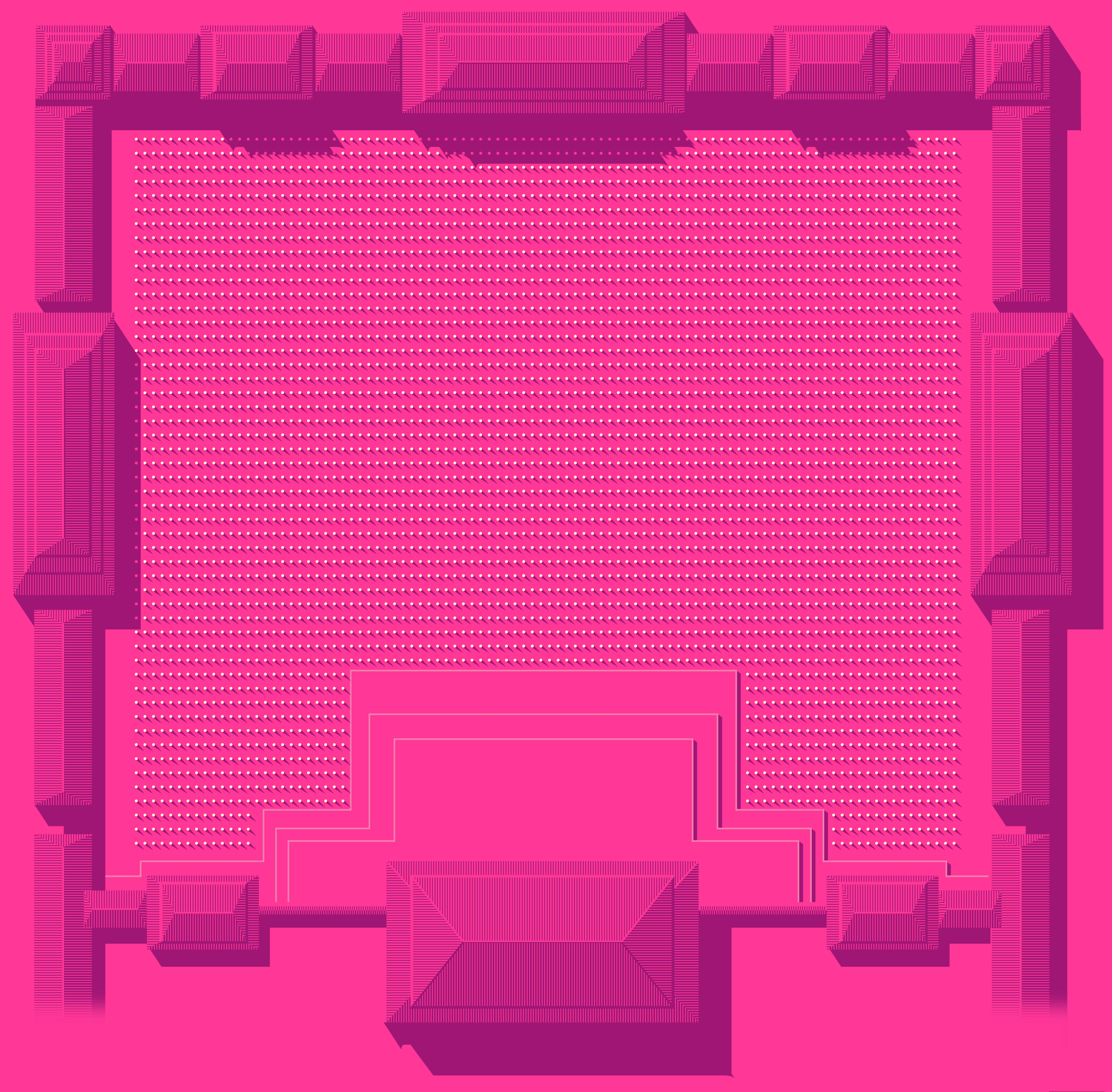

PARTThe Forbidden City’s unique architecture

By Marco Hernandez

-

II

PARTLife inside the Forbidden City

By Marcelo Duhalde

-

III

PARTThe collection, the odyssey of the objects

By Adolfo Arranz