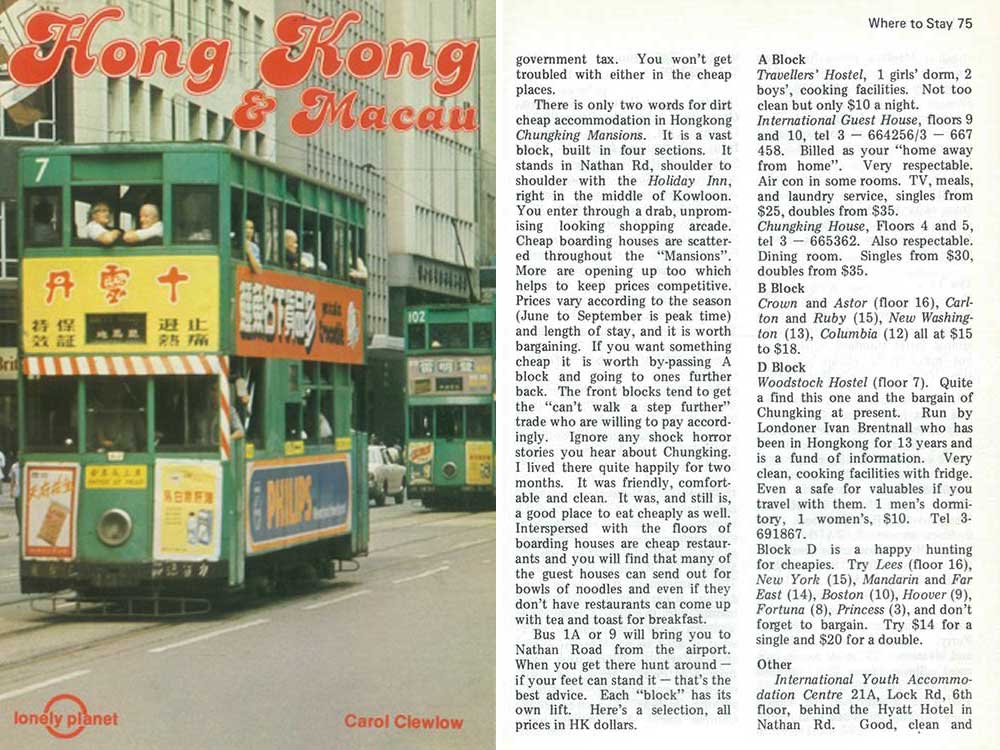

Home away from home

Are asylum seekers crossing the line?

Chungking Mansions plays a vital role for asylum seekers in Hong Kong. It is often their first port of call and a place to find support, with the Tsim Sha Tsui complex housing Christian Action’s Service Centre for Refugees and Asylum Seekers, the only drop-in centre of its kind in the city.

And for asylum seekers from South Asia and Africa, the dilapidated high-rise also provides a comfort factor, a place to meet people from their own country and find food from home. Cheap guesthouses, in a city with rents among the highest in the world, are another drawcard.

However, some from the building’s neighbourhood see it negatively. Kwan Sau-ling is one of them.

As Yau Tsim Mong district councillor, Kwan says the city’s asylum-seeker policy has led to a resurgence in bad behaviour in and around Chungking Mansions.

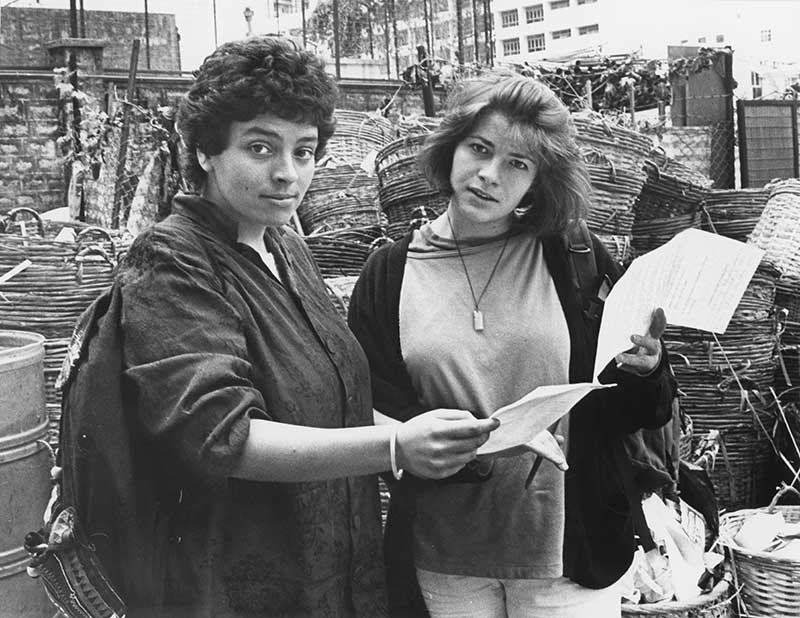

A throng of touts outside Chungking Mansions greets passers-by. But their offers of a watch, a bed, a meal or often drugs has sparked anger in the community. Their actions outside give a different impression to the work of refugee organisations inside. Photos: SCMP Pictures

She says the number of complaints filed by residents and pedestrians around the building has increased, with most involving assaults and harassment by South Asians who she claims are abusing the city’s immigration system.

“I receive more than 10 complaints about harassment, assault or fights every month. In the past that figure would have been for the whole year,” Kwan says. “I think it’s largely attributed to an influx of South Asian illegal workers staying on torture claims.”

Kwan’s concerns come on the heels of a government investigation last year into agencies using fraudulent documents to allow Indians to enter Hong Kong to claim asylum.

The city’s security chief, Lai Tung-kwok, says such activities are an abuse of the city’s non-refoulement policy after a Unified Screening Mechanism was implemented in 2014.

“They claim they come to Hong Kong to seek asylum, but they are working here as touts,” Kwan says. “They are troublemakers, scaring passers-by and creating an unfair competitive environment for businesses because the illegal workers are not bound by the minimum wage requirement.”

As a solution, Kwan wants authorities to speed up asylum seekers’ claims and evict those who are abusing the system. But it’s a huge task.

A higher acceptance rate for asylum seekers’ torture claims came after a 2013 ruling that meant immigration officers had to give equal weight to the prospect of “cruel, inhumane or degrading” treatment of a torture claimant’s return to where they came from.

Hong Kong has a non-refoulement screening mechanism to protect refugees from being sent to a place where they might be persecuted. Once such a claim is substantiated, the claimant is referred to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees for consideration of resettlement in a third country. That process, however, can take more than 10 years.

According to Immigration Department data, the city has more than 11,100 claims outstanding under the non-refoulement policy. That backlog of claims would take more than five years to resolve at the current rate of 2,000 a year.

In or out? Hong Kong's immigration numbers

Vietnamese

Indian

Pakistani

Bangladeshi

Indonesian

Illegal Immigrants

Overstayers

Others

The very low rate of substantiation – 0.3 per cent – has caused “grave concern” among some lawmakers.

The department has suggested they could speed up the resolution process to close cases within 15 weeks.

It’s no wonder then that asylum seekers in Hong Kong find illegal work, which the government aims to curb with a HK$1,500 a month housing subsidy, HK$1,200 in coupons for food, and HK$500 for utilities and transport.

“The objective of the assistance programme is to ensure that claimants will not, during their presence in Hong Kong, become destitute,” the briefing document said.

Matthew Tsoi, a security manager at Chungking Mansions, disagrees with claims the newcomers are violent or 'troublemakers'.

He says that while the increase in asylum seekers on the premises has added pressure, it is not a major headache.

“Most are here to make money by taking up low-paid jobs such as dishwashers, waiters and touts,” he says. “They are not here to commit crimes.”

More than five shopkeepers, guesthouse owners and frequent lodgers at Chungking Mansions told the Post they had seen a substantial improvement in security, with violence in steep decline, following the installation of hundreds of closed-circuit television cameras and the presence of a better-organised security team.

“Most are here to make money by taking up low-paid jobs such as dishwashers, waiters and touts. They are not here to commit crimes"

“Ten years ago there were just 13 security guards overseeing the entire building. Now we have twice that number and aim to hire more,” Tsoi says. “Also, 70 per cent of Chungking Mansions is under CCTV surveillance and we intend to boost this to 80 to 90 per cent.”

While acknowledging occasional violence in the building, the management office said it was usually between groups with business conflicts and in the form of fights with fists, not guns.

Tsoi says at times residents attribute the role of peacekeeper to him and his staff, but he sees it slightly differently.

“In fact we are called the Chungking police by many people,” he says. “But we’re more like firefighters, sorting out problems and calming tense situations.” Kenyan Peter Maina lived in Chungking Mansions for two months when he arrived in Hong Kong in 2014 as an asylum seeker. He didn’t find the place dangerous. “I felt at home on the premises and was less discriminated against there.

“People fight, but not for unusual reasons,” he says, “I avoided dark areas, particularly the back alleys – that way everything was fine.”

Another African asylum seeker, who declined to be identified, believes the sense of “insecurity” in the community is fuelled by a fear of dark-skinned people.

“My friends and I feel comfortable here because elsewhere people might get frightened when they see a group of black people walking side by side,” he says.

But even people who call Chungking Mansions home concede a rise in the number of touts has made it over-commercialised. Maina – who serves as general secretary of Refugee Union Hong Kong – says touts “selling clothes, phones, bags … everything” is “truly overwhelming”.

For Kwan, safety is a major issue. She says the increase in “non-genuine” asylum seekers coincided with a shortage of manpower in the police force, and recalls incidents where young women living nearby felt humiliated by touts of South Asian descent who approached them in Chungking Mansions as if they were sex workers.

She says illegal overstayers were once deported to their home country but today many torture claimants are waiting for the authorities to process their requests to stay, despite being arrested by police.

“You go to the consulates and check their backgrounds so you know whether they are facing death threats back home or whether they are policy abusers"

“I don’t understand why the Immigration Department takes so long reviewing applications,” she says. “It’s simple. You go to the consulates and check their backgrounds so you know whether they are facing death threats back home or whether they are policy abusers.”

Maina fears fraudulent asylum seekers “are spoiling the policy” for legitimate claimants. He also agrees that the application process for genuine applicants who have travelled thousands of kilometres to escape punishment ‒ possibly execution ‒ should be expedited.

“But there’s one thing to note here,” he says. With a monthly housing allowance of just HK$1,500 and monthly food coupons worth only HK$1,200, even some genuine asylum seekers are forced into the illegal work “just to survive”.