Chris Lau looks back at the violence that rocked one of Hong Kong’s busiest retail hubs and the aftermath as alleged rioters appear in court and the city’s political scene feels the true impact

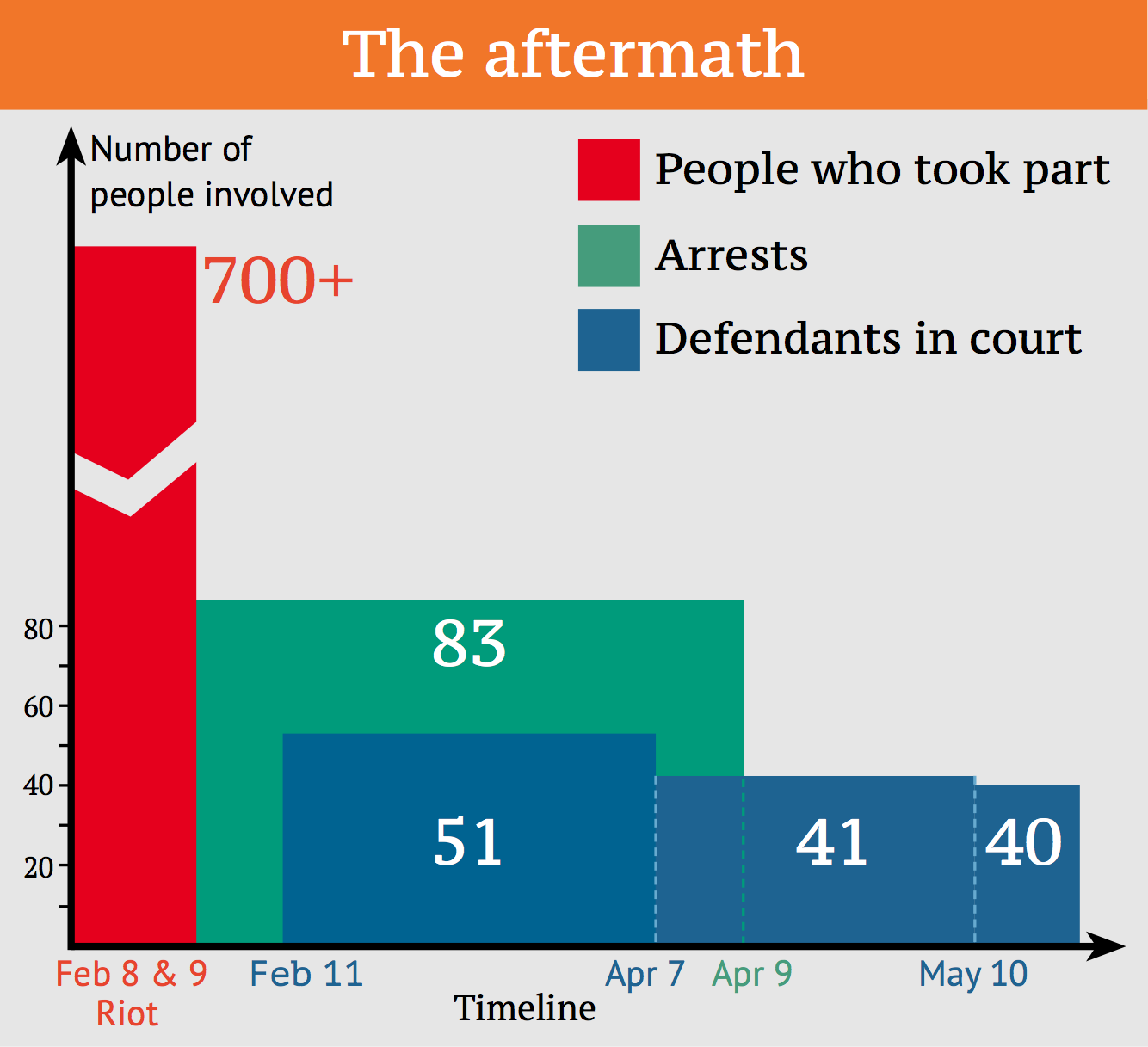

Defendants brought to court

Two thousand bricks prised from pavements and used as missiles to cause mayhem, 22 fires lit in defiance of order, 800 policemen dispatched to the scene at the height of the chaos, more than 700 alleged rioters on the rampage for over 10 hours, 130 injured by the end of it all.

Three months on, these figures may no longer seem as stunning, but on that fateful night of February 8, Hongkongers reeled in shock at the violence that rocked one of their beloved iconic shopping spots.

The first night of the Lunar New Year began with droves of supporters pouring onto one of the city’s busiest districts, Mong Kok, to show support for itinerant hawkers, some of whom sold curried fishball – a popular street food unique to the city.

The illegal peddlers were allegedly being targeted for fines by officers from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. The supporters became rowdy and threatened to push a cart of boiling oil at the officers – whether this act was orchestrated or the spark that lighted the conflagration remains unclear to this day. But before long, the ensuing melee led to a traffic policeman firing two warning shots into the night sky at Argyle Street, one of the protesters’ strongholds during the Occupy demonstrations of 2014.

But the scenes of that night were a far cry from those peaceful mass protests in the name of democracy. Fires – set off by protesters wearing black surgical masks – burned in several parts of the district, including Sai Yeung Choi South and Soy streets. Mong Kok was turned into a war zone that night.

It was arguably the biggest outbreak of mob violence since the 1967 disturbances during which bomb attacks were plotted by the leftists against the British colonial government.

The tumult of that evening has since come to be known as the Mong Kok riot – with the word “riot” also becoming a point of contention by some who said the government was exaggerating the violence and others who insisted on calling a spade a spade.

Kwong, a hawker who declined to give his full name, was selling egg waffle – or gai daan tsai – with his elderly mother that night and had to move his cart away repeatedly. “I was afraid my mum would get injured,” said Kwong, who stuck around until 4am that night.

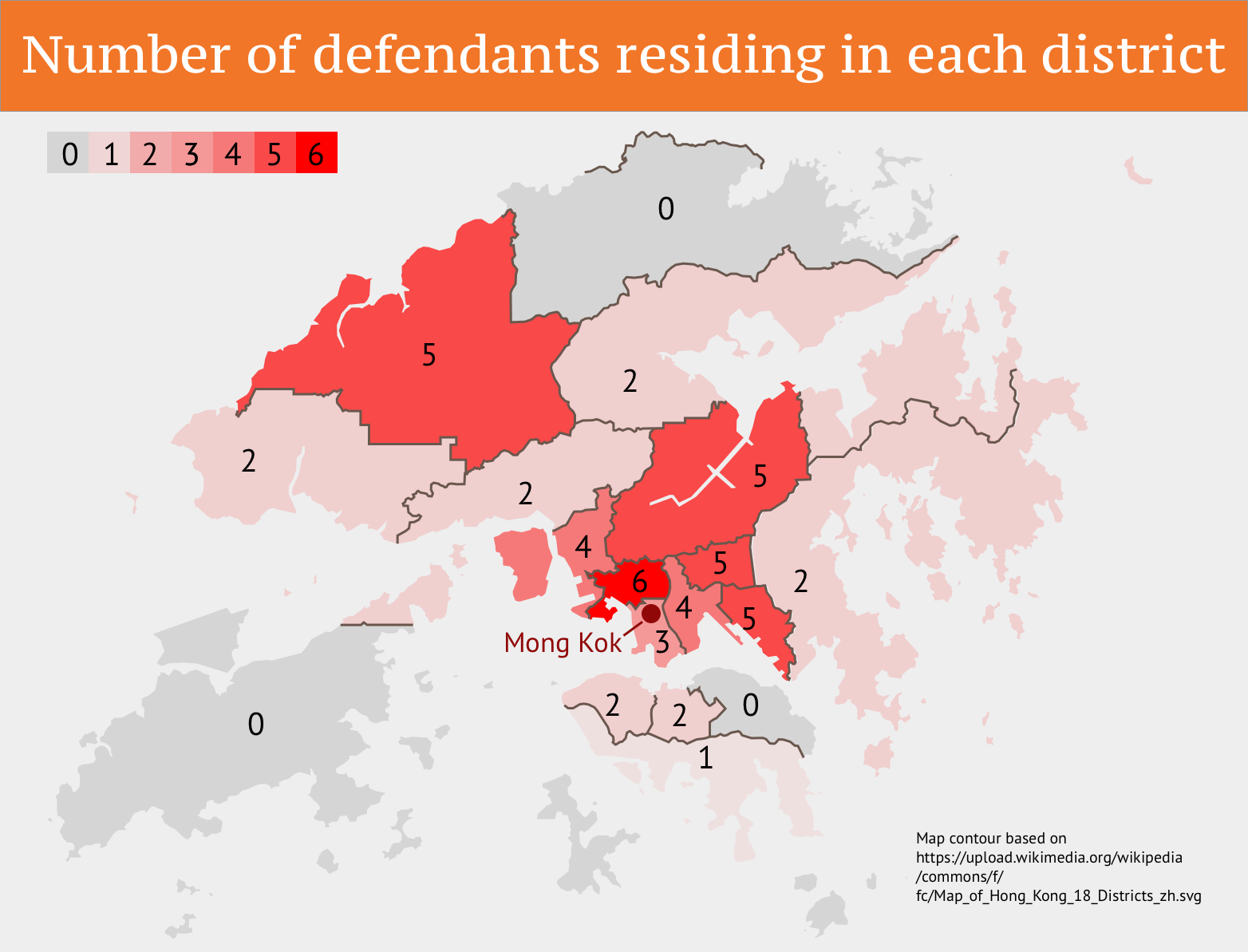

Another hawker, Ada Ho, felt safe, but was upset that her fishball trade had to close early. Instead of helping, the supporters hurt her business, she said. Police made 61 arrests initially, but over the past three months, the figure has risen to 83. Of those arrested, 51 people have been brought to court. Edward Leung Tin-kei, the spokesman of radical localist group Hong Kong Indigenous, was among them.

Also charged was fellow group member Ray Wong Toi-yeung, who issued his “final message to Hongkongers” in a manner reminiscent of Ten Years, a local dystopian film that featured scenes of self-immolation and spoke to the fears of a city absorbed by the motherland.

All but one of the defendants face one count of rioting and are mostly in their 20s and 30s. Most are male and either students or unemployed. One defendant faces an additional count of arson. But 11 out of the 51 have had their charges dropped since then due to a lack of evidence.

Three months on, the legacy of the violent clashes has not only shaken the city’s political discourse but has become a defining moment signalling the arrival of a new movement towards independence.

While the Hong Kong government, led by Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, condemned the violence and called it a riot, top mainland officials branded the instigators and participants – believed to be inspired by the localist movement – “separatists”.

The government has refused to set up an independent inquiry to look into the causes of the riot, but the Legislative Council will have its own non-legally binding investigation, though no date has been set.

Under another line drawn in the sand, several university student leaders have openly declared their support for localism. Edward Leung, the localist candidate who took part in the Legco by-election for the New Territories East constituency, also came in a respectable third, winning 66,524 of 432,581 valid votes just weeks after the riot.

The government only focused on the clashes…but not the causes.

The government only focused on the clashes…but not the causes.

One of the former defendants, activist Derek Lam Shun-hin, said he was not surprised.

A member of Demosisto – a new party seeking self-determination for the city recently founded by youth activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung – Lam attributed Leung’s rise in part to the government’s poor handling of the riot.

“The government only focused on the clashes…but not the causes” he said. So even if there was an independent inquiry, he added, it would not serve its purpose to study the real cause.

But by March, when the country’s top leaders met during the annual Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and National People’s Congress sessions in Beijing, there were no harsh words. In an exclusive interview, Feng Wei, deputy director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, told the Post that he was fully prepared to accept young radicals winning Legco seats in the coming September elections.

Uncertainties lie ahead.

Chung Kim-wah, assistant professor at Polytechnic University’s Department of Applied Social Sciences, felt the central and Hong Kong governments had come to realise that the hardline approach was not a workable solution. “So Beijing has relented,” he said.

Meanwhile, Ten Years – unavailable on the mainland presumably because of its pessimistic view of the motherland – went on to win Best Film at the Hong Kong Film Awards in April.

But just days before the film took home the top prize, concerns were reignited when the city gave birth to the Hong Kong National Party, the first party to openly canvass for outright independence. Local and mainland officials were quick to weigh in on whether doing so amounted to a criminal offence, now the city’s latest talking point.

Chinese University political scientist Ivan Choy Chi-keung said groups had been set up on the mainland to study Hong Kong youth since the Mong Kok riot.

With the Legco elections looming closer, Chung said: “Uncertainties lie ahead.”

There is no uncertainty, however – and both Choy and Chung agree – that the handling of the riot will have some effect on the chief executive race next year.

Activist Lam warned if the government did not improve, there were bound to be clashes again.

I am not sure whether we will still be allowed to set up a stall next year.

Three months on, Mong Kok bears no scars of the unhappy episode, but the hawkers remain wary.

Kwong who has been hawking on the first day of every Lunar New Year since 1997, cited stepped-up enforcement against illegal hawkers. He said wistfully: “I am not sure whether we will still be allowed to set up a stall next year.”